Introduction

SaaS development in 2026 is not about picking a trendy stack. It is about meeting baseline expectations: fast pages, predictable APIs, strong tenant isolation, and audits that do not turn into a fire drill. Users compare your product to the best tools they already use. They notice latency, broken permissions, and noisy alerts.

The good news is that the environment is mature. We have boring, effective defaults for auth, observability, and deployments. The bad news is that “boring” still requires discipline. Small shortcuts in data modeling, background jobs, or IAM show up later as cost spikes and on call pain.

At Apptension we see the same pattern across products we build and maintain, including our own SaaS Teamdeck (resource planning and time tracking) and delivery work for data heavy platforms like Tessellate and Platform. The teams that ship consistently do a few things well: they constrain complexity early, they measure everything, and they treat security as a feature with acceptance criteria.

Architecture in 2026: modular monolith first, split when forced

Microservices are still a valid choice, but they are no longer the default answer. Many SaaS teams in 2026 start with a modular monolith and carve out services only when they have a clear reason. That reason is usually one of these: a hard scaling boundary (CPU heavy workloads), a different reliability profile (jobs vs API), or a separate compliance scope.

A modular monolith works when you enforce module boundaries in code, not in a slide deck. It also works when you keep the “platform” surface area small: one API gateway, one auth flow, one event backbone. When teams skip this discipline, the monolith becomes a ball of mud and the later split gets expensive.

Boundary rules that prevent accidental coupling

Module boundaries fail in small, boring ways. A billing module reads user tables directly “just this once.” A reporting query joins across five domains because it is faster to ship. A background worker imports internal files from the API module. These are not dramatic mistakes. They are the start of long term friction.

We usually enforce boundaries with a mix of conventions and tooling. Conventions include “no cross module ORM imports” and “only call a module through its public interface.” Tooling includes TypeScript path aliases, lint rules, and code ownership in reviews. For larger codebases, we also add architectural tests that fail CI when a module imports forbidden paths.

- Rule: Each module owns its data access layer. Other modules call it through services or repositories, not raw queries.

- Rule: Events cross boundaries. Direct calls are allowed only inside a bounded context.

- Rule: Shared code is a small “kernel,” not a dumping ground. If it grows, split it.

Where microservices still make sense

Microservices earn their keep when they reduce blast radius or let teams move independently. A common split we implement is: API monolith + worker service + search service. Workers often need different scaling, different timeouts, and a different failure mode. Search often needs specialized storage and indexing.

Microservices fail when teams use them to avoid making decisions. If you split too early, you pay for extra deployments, extra observability, and extra failure modes. You also pay in local development time. In 2026, the “right” architecture is often the one that keeps the number of moving parts low until product usage forces your hand.

Most early outages we debug are not about raw traffic. They come from unclear boundaries: duplicate writes, race conditions between services, and permissions checked in one place but not another.

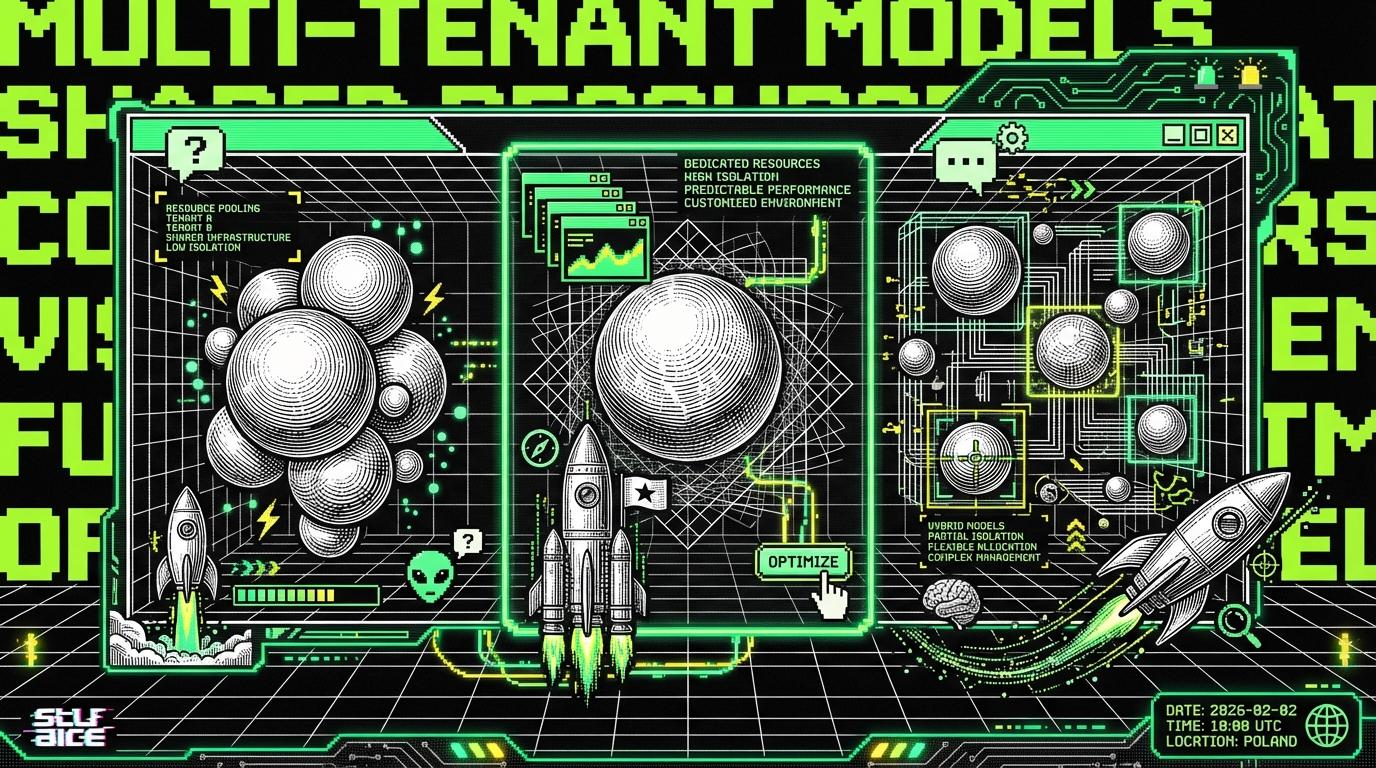

Multi tenancy and data isolation: the core SaaS problem

Multi tenancy is still where SaaS engineering gets real. It touches data modeling, caching, authorization, and observability. In 2026, customers expect isolation by default. They also expect exports, deletion, and audit trails. If you treat this as “later,” you will rewrite large parts of the system.

There are three common models: shared database with tenant key, database per tenant, and schema per tenant. Shared database is cheapest to run and easiest to operate at small scale. It is also easiest to get wrong. Database per tenant is easier to reason about for isolation and some compliance demands, but it adds operational overhead and can complicate analytics.

Practical patterns for shared-database tenancy

If you choose shared database, you need guardrails that prevent “missing tenant_id” bugs. We typically push tenant scoping down into the data access layer and make it hard to bypass. Row level security (RLS) in Postgres helps, but it is not a silver bullet. You still need correct session variables, correct roles, and tests that prove isolation.

We also recommend adding tenant scoping to every cache key and every queue message. It sounds obvious, but it is easy to miss when a feature team adds caching late. A good rule is: if a piece of state can contain customer data, it must be keyed by tenant and environment.

// Example: tenant-scoped repository wrapper

// Works with any query builder/ORM as long as you control the entry point. type TenantContext = { tenantId: string; userId: string; roles: string[];

};

class TenantRepo {

constructor(private db: any, private ctx: TenantContext) {}

async listProjects() {

return this.db.project.findMany({

where: {

tenantId: this.ctx.tenantId

},

orderBy: {

createdAt: "desc"

},

});

}

async getProject(id: string) {

return this.db.project.findFirst({

where: {

id,

tenantId: this.ctx.tenantId

},

});

}

}Tenant-aware observability

Isolation is not only about data reads. It is also about what you can see in logs and traces. In 2026, most teams carry a “tenant_id” through request context and attach it to logs, metrics, and traces. That lets you answer questions like “is this incident global or one tenant?” in minutes, not hours.

The failure mode is over-logging. If you log payloads with personal data, tenant tags will not save you. We usually log identifiers and counts, not raw content. For debugging, we rely on structured logs, trace sampling, and short lived debug flags that require elevated access.

- Include

tenant_idandrequest_idin structured logs. - Tag traces with

tenant_id, but avoid tagging with user email or names. - Expose per-tenant rate limiting and quotas to stop noisy neighbors.

Backend stack: TypeScript still dominates, but the shape changed

TypeScript remains a common default for SaaS backends in 2026, especially for teams that want one language across frontend and backend. The environment stabilized around a few patterns: framework-based HTTP layers, strong schema validation, and code-first or schema-first APIs. Node is fast enough for most SaaS workloads when you keep hot paths simple and push heavy work to workers.

We still see Ruby, Python, Go, and Java in production SaaS, and they are fine choices. The more important shift is not the language. It is the approach: strict input validation, explicit error handling, and predictable background processing. Teams that skip these end up with “unknown unknowns” in production.

API design: REST is fine, GraphQL is fine, contracts are mandatory

REST remains the simplest option for most products. GraphQL still fits products with complex, user-driven data fetching and many client surfaces. What changed is the expectation around contracts. In 2026, teams treat API schemas as build artifacts that gate merges. They generate types, clients, and mocks from those schemas.

At Apptension we often ship with an OpenAPI contract for REST or a GraphQL schema with persisted operations. Persisted operations help control query cost and reduce abuse. They also make caching and observability easier because the operation name becomes a stable dimension.

// Example: Zod validation + typed handler (framework-agnostic)

import {

z

} from "zod";

const CreateProject = z.object({

name: z.string().min(1).max(120),

color: z.string().regex(/^#[0-9a-fA-F]{6}$/).optional(),

});

type CreateProjectInput = z.infer;

export async function createProjectHandler(req: any, res: any) {

const parsed = CreateProject.safeParse(req.body);

if (!parsed.success) {

return res.status(400).json({

error: "VALIDATION_ERROR",

details: parsed.error.flatten(),

});

}

const input: CreateProjectInput = parsed.data;

const project = await req.services.projects.create({

tenantId: req.ctx.tenantId,

name: input.name,

color: input.color ?? null,

});

return res.status(201).json({

project

});

}Background jobs: make them boring and inspectable

Most SaaS products are job systems with an API attached. Imports, exports, billing, notifications, and AI tasks all happen off the request path. In 2026, the baseline is: idempotent jobs, explicit retries, and a dead letter queue you actually monitor. If a job can run twice, it must not corrupt data.

We usually implement a job envelope that includes tenant context, a stable idempotency key, and a version. The version matters when you change payload shape. Without it, old messages can crash new workers and you get a silent backlog.

- Define the job payload schema and validate it in the worker.

- Store an idempotency record keyed by

tenant_idandjob_key. - Make retries explicit and bounded (for example: 10 attempts with exponential backoff).

- Expose job status in the admin UI for support and engineering.

Frontend in 2026: fast pages, fewer client bugs, stricter boundaries

Frontend stacks converged around a few stable choices. React is still common, often with Next.js or similar meta frameworks. The big change is that teams are more deliberate about what runs on the server versus the client. Server rendering and server actions reduce bundle size and avoid shipping secrets. Client code stays focused on interaction, not data plumbing.

What fails is overusing client state and re-fetching. If every component owns its own data calls, you get waterfall requests and inconsistent caching. If you push everything to the server without care, you can create chatty server side rendering and slow time to first byte. The goal is balance, measured with real metrics.

Design systems and component governance

In 2026, design systems are not a nice-to-have for SaaS. They reduce UI drift and speed up feature work. The failure mode is building a component library that is too abstract to use. We prefer a small set of primitives plus a set of product components that are allowed to evolve with the product.

For Teamdeck-style apps with dense tables and scheduling views, UI performance matters. Virtualization, memoization, and predictable state updates make the difference between a smooth timeline and a laggy one. We measure interaction latency and long tasks in the browser, not only API latency.

- Keep a strict boundary between presentational components and data loaders.

- Use a single caching layer (for example, a query client) rather than ad hoc fetch calls.

- Set budgets: bundle size, route-level JS, and acceptable render times for heavy views.

Typed contracts across the stack

Type safety helps most when it crosses the API boundary. Generating types from OpenAPI or GraphQL reduces “stringly typed” bugs. It also makes refactors cheaper. The key is to treat the schema as the source of truth and keep manual types to a minimum.

Typed contracts do not replace runtime validation. Browsers, proxies, and third party integrations will still send bad inputs. We combine types with schema validators on both ends. That combination catches errors early and keeps production logs quieter.

Security, compliance, and privacy: engineering work, not paperwork

SaaS buyers in 2026 ask for proof. They want SSO, audit logs, data retention controls, and clear incident handling. Even small B2B products get security questionnaires. If your system cannot answer “who accessed what and when,” you will lose deals or spend weeks patching gaps under pressure.

Security work fails when it is bolted on. The practical approach is to implement a small set of controls early and expand them as the product grows. That includes least-privilege IAM, secret management, encryption defaults, and secure-by-default endpoints. It also includes tests that assert access control, not only happy path behavior.

Security bugs in SaaS are often authorization bugs. The fix is rarely a crypto library. It is consistent permission checks, tenant scoping, and good tests.

Authorization: policy engines vs application code

There are two common approaches: implement authorization in application code, or use a policy engine. Policy engines can help when rules get complex and you need a central place to reason about them. They also add another moving part and can become a bottleneck if misused. For many products, well-structured application code with a clear permission model is enough.

We often implement permissions as explicit checks near the boundary of each use case. We keep them testable and we avoid scattering them across controllers. When rules get more complex (for example, role + project membership + feature flags), we consider a policy layer with a small API.

// Example: explicit permission check in a use-case type Ctx = { tenantId: string; userId: string; roles: string[] }; type Project = { id: string; tenantId: string; ownerId: string }; afunction canEditProject(ctx: Ctx, project: Project) { if (project.tenantId !== ctx.tenantId) return false; if (ctx.roles.includes("admin")) return true; return project.ownerId === ctx.userId;

}

export async function renameProject(ctx: Ctx, projectId: string, name: string,

db: any) {

const project = await db.project.findUnique({

where: {

id: projectId

}

});

if (!project || project.tenantId !== ctx.tenantId) throw new Error(

"NOT_FOUND");

if (!canEditProject(ctx, project)) throw new Error("FORBIDDEN");

return db.project.update({

where: {

id: projectId

},

data: {

name

}

});

}SSO, SCIM, and audit logs: the B2B baseline

SSO is not only a login feature. It changes identity lifecycle, support workflows, and incident response. SCIM adds provisioning and deprovisioning, which reduces stale accounts. The failure mode is partial implementations that create duplicate users or broken role mappings. You need deterministic identifiers and careful merge rules.

Audit logs need structure. A text log is not enough when a customer asks for “all permission changes in the last 30 days.” We store audit events as append-only records with actor, target, action, and a diff. We also include request metadata like IP and user agent when it is relevant and lawful to store.

- Store audit events in a dedicated table with partitioning by time if volume is high.

- Expose export with filters: time range, actor, resource type, action.

- Redact sensitive fields. Store references, not raw secrets.

AI features in SaaS: useful when constrained, painful when vague

By 2026, “add AI” is a common requirement, but it is rarely specific. The technical work starts with scoping. Is this summarization, search, classification, or automation? Each has different latency, cost, and evaluation needs. If you cannot define a success metric, you cannot tune the system.

We have shipped AI-assisted features where the model output is advisory, not authoritative. That reduces risk. For example: draft text, suggest tags, propose mappings, or highlight anomalies for review. Fully automated actions can work, but they need guardrails and a rollback path.

RAG pipelines: retrieval quality matters more than model choice

Retrieval augmented generation (RAG) is still a strong default for SaaS knowledge features. The hard part is not calling a model API. It is building clean documents, stable chunking, and good metadata. If your chunks mix tenants or environments, you have a breach. If your metadata is weak, you get irrelevant answers.

We treat embeddings as an index, not a database. The source of truth stays in your primary store. We version the embedding pipeline so we can re-embed when chunking changes. We also log retrieval sets (document IDs, not content) to debug why an answer was wrong.

// Example: tenant-safe retrieval query (pseudo-code) type RetrievalQuery = { tenantId: string; queryEmbedding: number[]; topK: number;

};

export async function retrieveDocs(q: RetrievalQuery, vectorDb: any) {

return vectorDb.search({

topK: q.topK,

vector: q.queryEmbedding,

filter: {

tenantId: q.tenantId,

environment: "prod",

docStatus: "active",

},

includeMetadata: true,

});

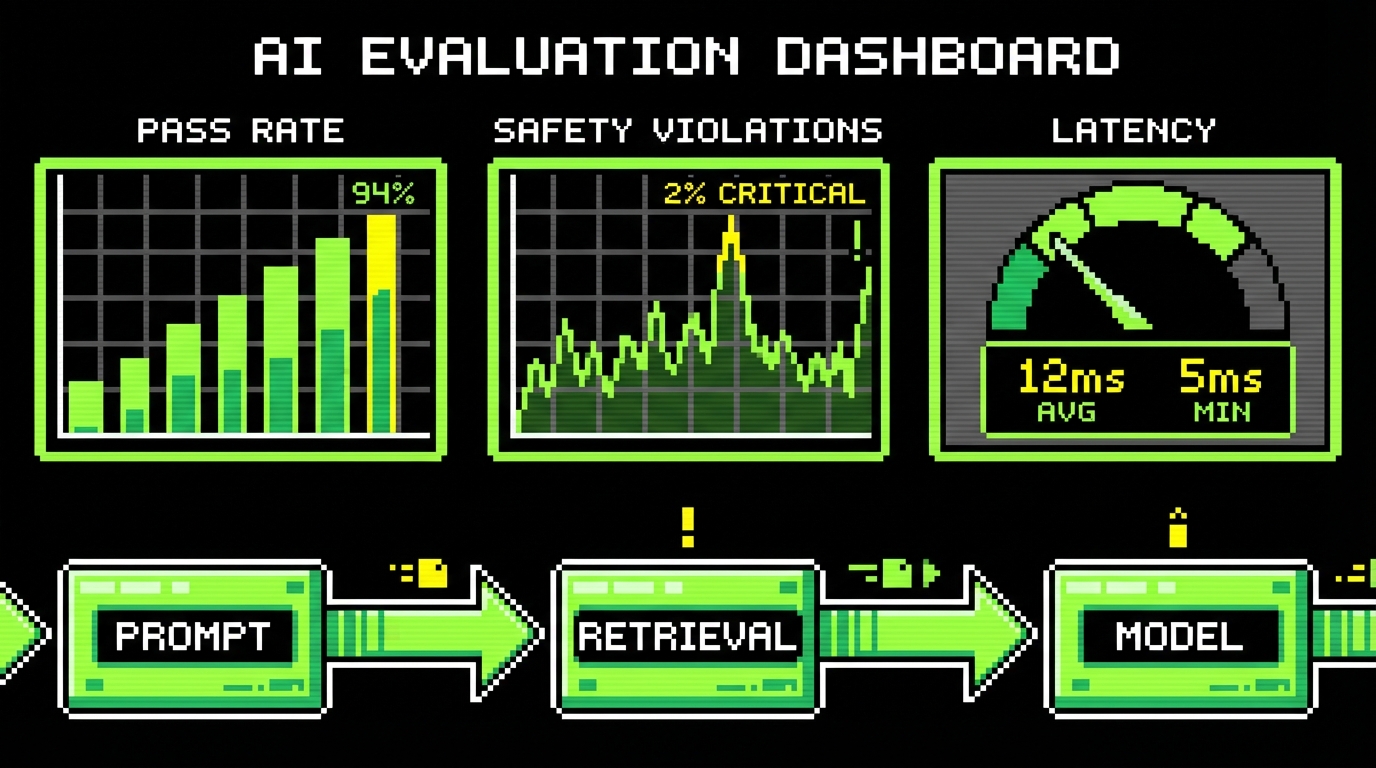

}Cost, latency, and evaluation

AI features can quietly become your largest variable cost. The fix is measurement and constraints. Cache model outputs when inputs are stable. Batch background tasks. Use smaller models for classification and routing. Reserve larger models for steps that truly need them.

Evaluation needs a loop. We define a small dataset of real examples, run offline checks, then run online A/B tests with guardrails. We also track “user corrected output” as a signal. If users keep editing the same mistakes, your prompt or retrieval is wrong.

- Define a target: for example, “reduce time to complete task by 20%” or “cut support tickets by 10%.”

- Instrument: log prompt version, retrieval IDs, latency, and user actions after output.

- Constrain: set timeouts and fallbacks so the UI does not hang.

- Review: sample outputs weekly and update the dataset.

Reliability and delivery: what keeps SaaS alive at scale

Reliability in 2026 is not a single tool. It is a set of habits: measured SLIs, tested rollbacks, and predictable deployments. Most SaaS incidents we see come from changes, not from traffic spikes. That means CI/CD quality matters as much as runtime performance.

At Apptension we often start projects with a proven baseline for SaaS delivery. The point is not speed for its own sake. It is consistency: the same environment setup, the same observability defaults, the same release process. When teams reinvent this per project, they waste weeks and still miss basics.

Observability: traces for debugging, metrics for decisions

Logs help you read what happened. Traces help you find where it happened. Metrics help you decide if it matters. In 2026, teams that only log are slow during incidents. Teams that only trace can drown in data. We aim for a small set of dashboards that answer common questions fast.

We usually define SLIs per user-facing action: login, load dashboard, create record, export file. We measure p50, p95, and error rates. We also track queue depth and job age for worker systems. When job age climbs, customers feel it even if the API looks fine.

- API: request rate, error rate, latency percentiles, saturation (CPU, DB connections).

- DB: slow queries, lock time, replication lag (if used), storage growth per tenant.

- Workers: queue depth, oldest message age, retry counts, dead letter volume.

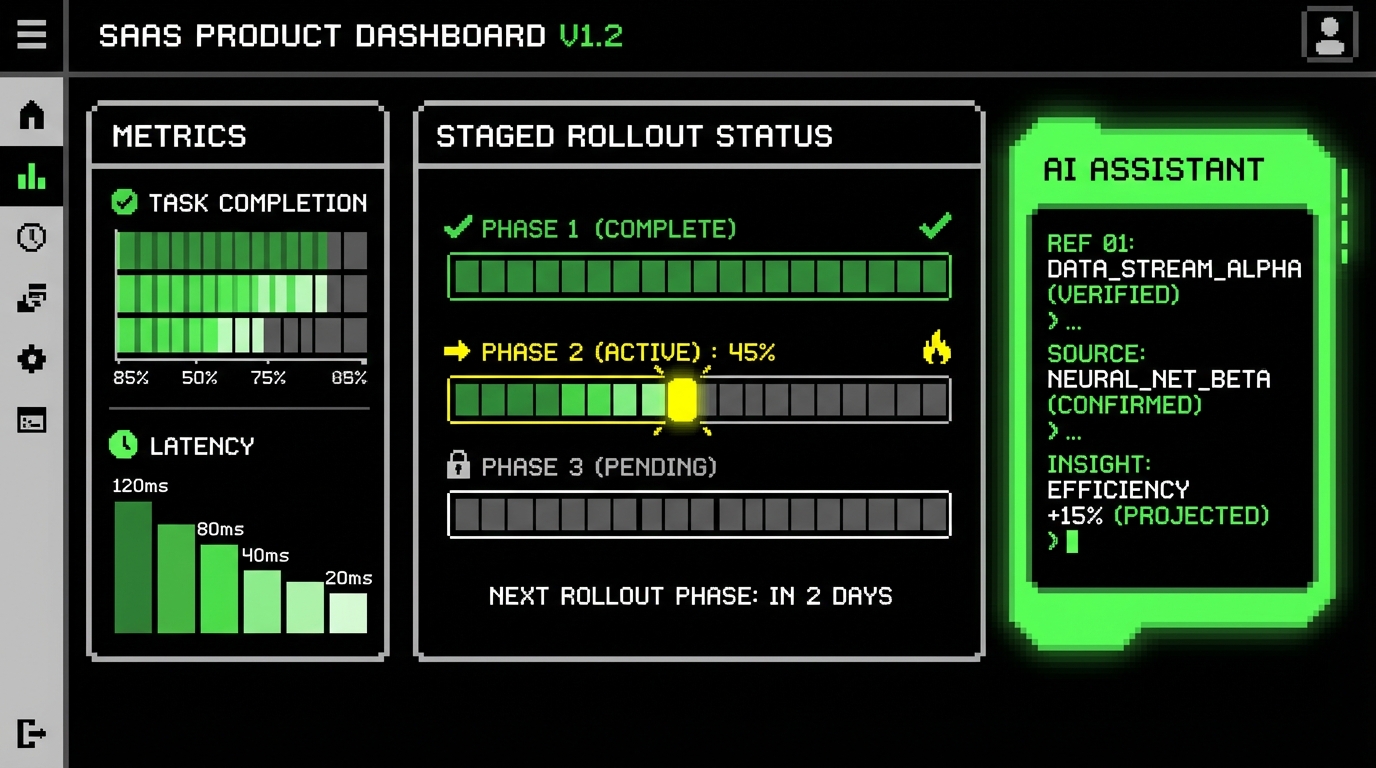

Deployment patterns that reduce risk

Blue-green and canary releases are common, but they only help if the app supports them. You need backward-compatible migrations and feature flags that can disable a path fast. The failure mode is a migration that blocks writes or a flag that is not wired correctly. That is how you end up rolling back code but not data.

We prefer small releases with clear ownership. If a release includes ten unrelated features, debugging becomes a guessing game. We also keep a playbook for rollback, including how to pause workers, how to drain queues, and how to revert flags. These steps should be practiced, not discovered during an incident.

A safe deployment is usually boring: small diff, measurable impact, and a fast way back.

Conclusion

SaaS development in 2026 rewards teams that treat fundamentals as product work. Tenant isolation, permission checks, job reliability, and observability are not optional. They are the difference between steady shipping and constant firefighting. The stacks are mature, but the discipline still takes effort.

If you are planning a new SaaS, start with constraints. Pick a modular monolith unless you have a strong reason not to. Decide on a tenancy model early and test it aggressively. Build a job system that you can inspect. Add AI features only when you can define success and measure it. Then ship in small steps, watch your metrics, and keep the system understandable.