Classic QA assumes the same input yields the same output. AI breaks that. Two runs can differ because the model is probabilistic, the prompt changes, the retrieval index updates, or the vendor ships a silent model revision. If you keep testing AI like a normal form validation flow, you will miss the failures that matter: unsafe content, wrong answers stated confidently, and slow responses that time out in production.

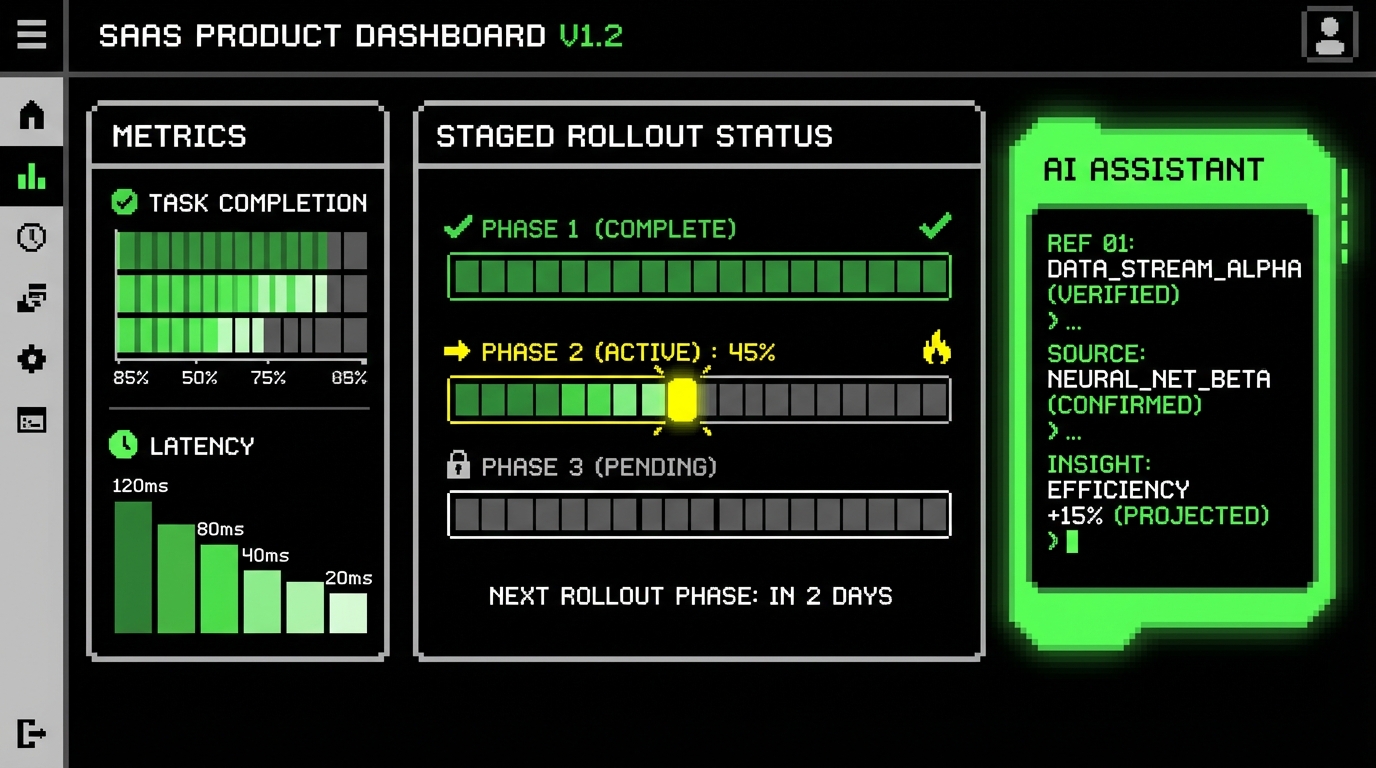

In Apptension delivery, we treat AI features as products inside the product. They need their own test data, their own quality gates, and their own monitoring. The goal is not “perfect accuracy.” The goal is predictable behavior within a defined risk envelope, backed by numbers you can track sprint to sprint and release to release.

This article lays out a QA approach for the AI era. It covers what to test (model, prompt, retrieval, and orchestration), how to automate evaluation, which metrics to use, and where teams usually fool themselves.

What changes in QA when outputs are probabilistic

With AI, your system has more “moving parts” than a typical web app flow. The output depends on the model, the prompt template, the user input, the retrieved context, and the decoding settings (like temperature, which controls randomness). A regression may come from a prompt edit, a new document added to the search index, or a model provider update. QA has to cover the whole chain, not just the UI.

That means you stop asking “does this return the correct string?” and start asking “does this meet a measurable standard for this task?” For example, a support assistant might be allowed to paraphrase, but it must always cite the correct policy section and must never invent refund rules. A content generator might be allowed to be creative, but it must keep reading level between grade 7 and 9 and avoid restricted claims like medical advice.

It also changes how you think about test environments. In a deterministic service, staging can be “close enough.” In an AI system, staging needs the same prompt versions, the same retrieval corpus snapshot, and the same model version (or at least a pinned alias). Otherwise you cannot explain why a test passed yesterday and failed today.

Define “quality” per use case, not per model

Teams often start by evaluating the model in isolation, then later discover the real failures come from the surrounding system. A model might score well on a benchmark, but your prompt asks it to do three tasks at once, or your retrieval returns irrelevant snippets. QA should define acceptance criteria at the product level, tied to user outcomes.

Concrete example: for an AI “meeting notes” feature, quality might mean (1) correct action items, (2) correct owners, and (3) no invented decisions. You can measure this with Action Item Precision (percentage of extracted action items that truly exist in the transcript) and Owner Accuracy (percentage where the assigned person matches the transcript). Those are more useful than a generic “LLM accuracy” label.

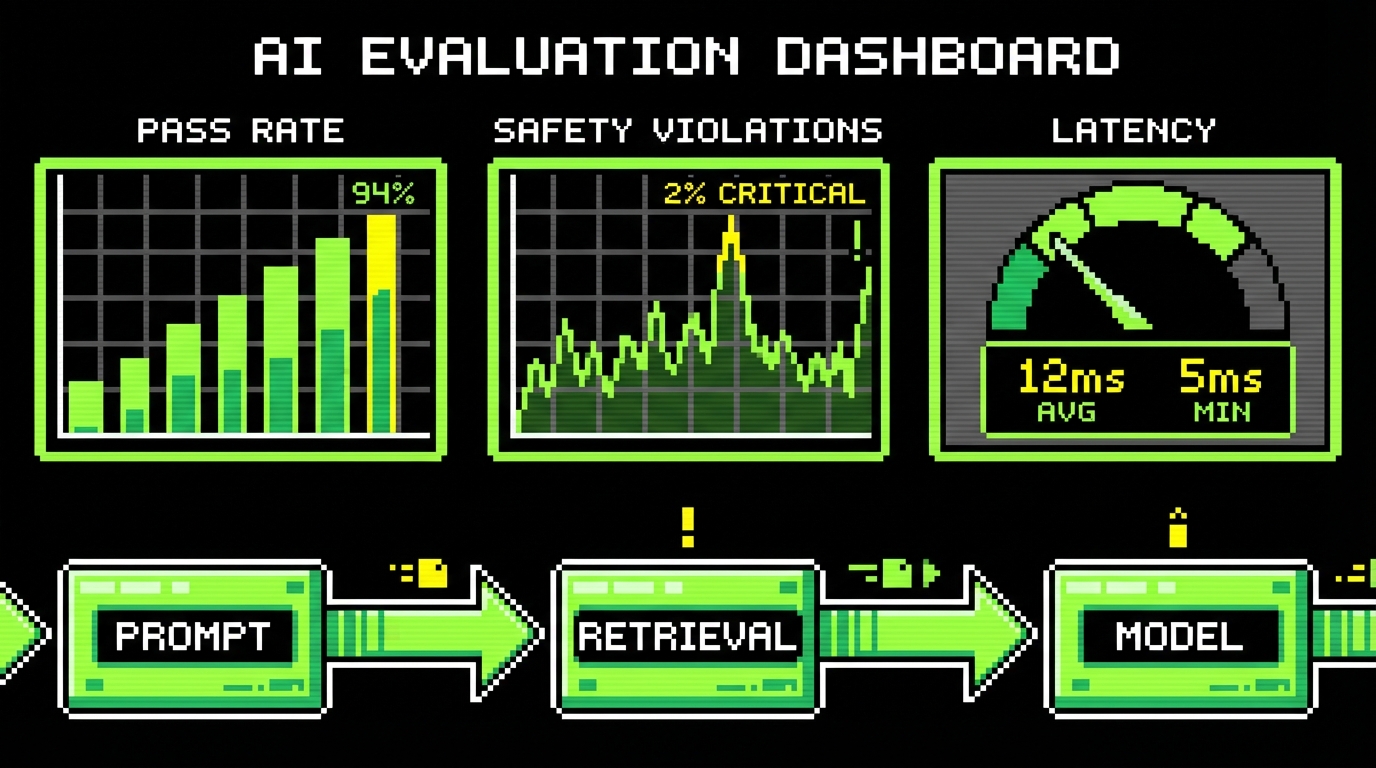

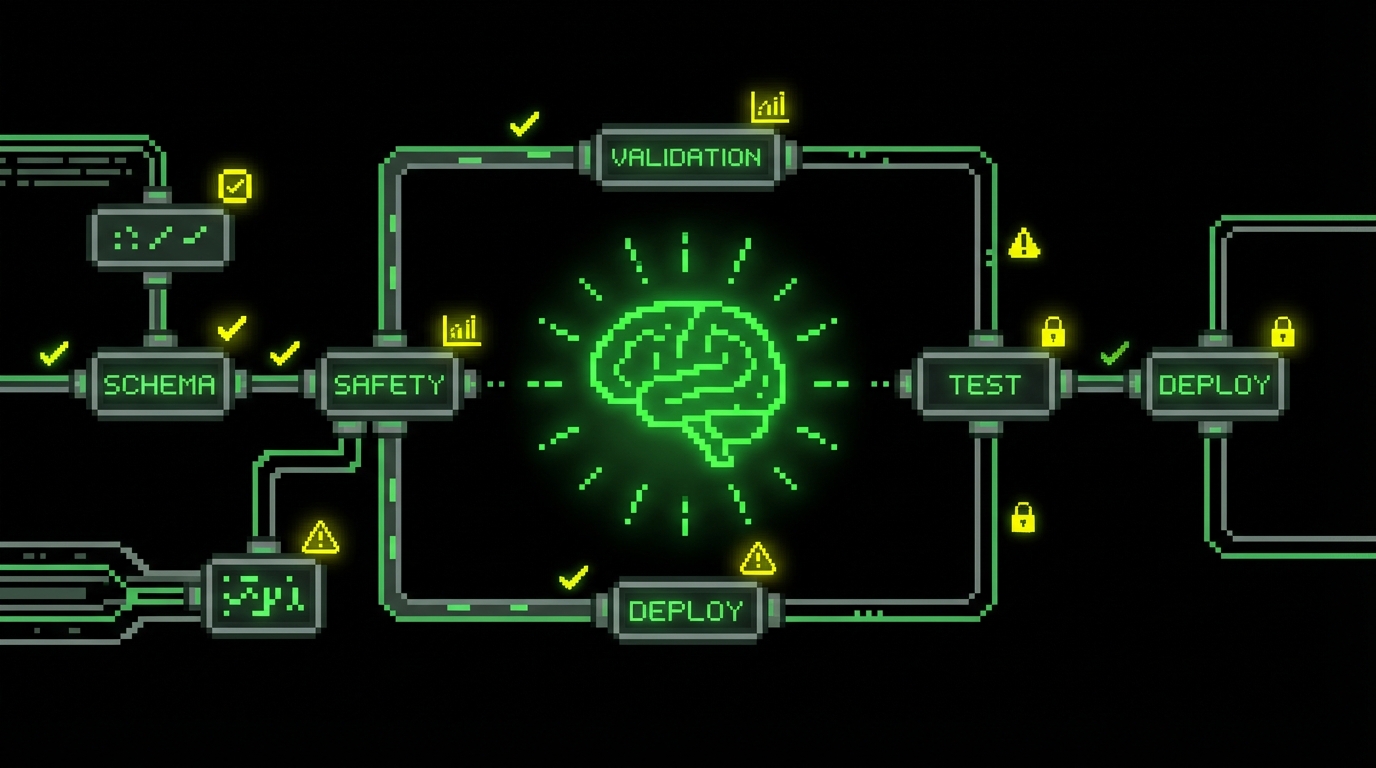

Map the AI surface area: model, prompt, retrieval, and glue code

AI failures cluster around four layers. If you do not name them, bugs bounce between roles and never get fixed. QA should maintain a simple map of what can change and what needs tests.

Model layer includes the vendor or self hosted model, its version, and its parameters. A change here can alter tone, refusal behavior, or latency. Prompt layer includes system prompts, templates, and few shot examples. A small wording change can flip behavior. Retrieval layer (RAG) includes chunking, embeddings, indexing, and ranking. Bad retrieval makes good models look dumb. Glue code includes function calling, tool permissions, caching, and post processing rules, which often cause the most severe incidents (like sending an email to the wrong address).

At Apptension we usually turn this map into a checklist for each AI feature. It becomes part of the definition of done: “prompt version tagged,” “evaluation set updated,” “latency budget verified,” and “drift monitors enabled.” It sounds boring, but it prevents the common failure mode where the prompt is edited in a hurry and nobody can trace what changed.

Threat model the feature before you write tests

Threat modeling is not only for security teams. For AI QA, it helps you decide what to test first. A threat model is a list of plausible failures, their impact, and the controls you will use. For example: “prompt injection causes the assistant to reveal internal documents” is high impact, so you add tests that attempt to override instructions and you validate that tool access is restricted.

Make the threats specific. “Hallucination” is vague. “Invents a cancellation policy and tells the user they can refund after 60 days” is testable. You can then build a small set of adversarial prompts and expected constraints, such as “must respond with ‘I don’t know’ when policy is not in retrieved context.”

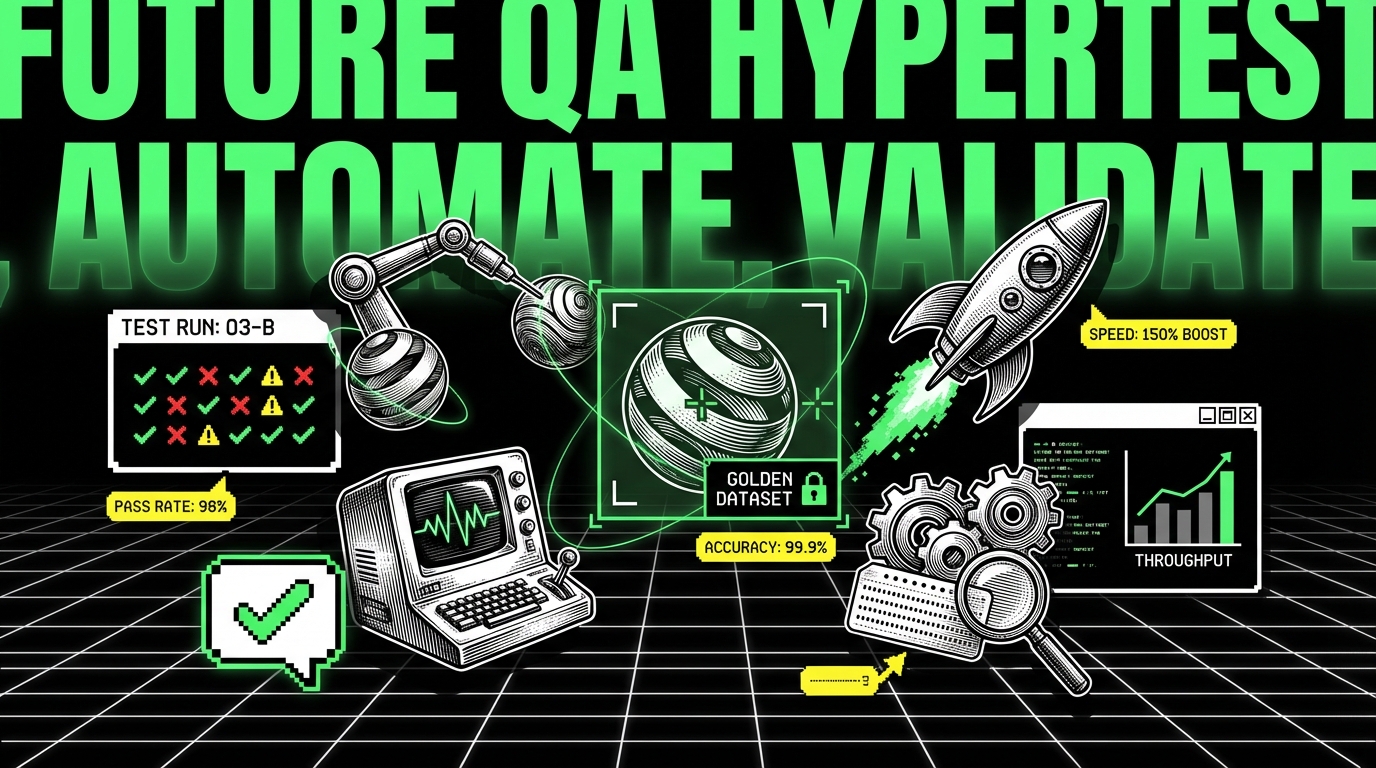

Build an evaluation harness, not a pile of screenshots

Manual exploratory testing still matters, but it cannot be the only line of defense. AI features need an evaluation harness: a repeatable way to run many test cases, collect outputs, score them, and compare results across versions. Think of it like unit tests plus performance tests plus safety tests, all executed against a probabilistic component.

A practical harness includes (1) a dataset of inputs, (2) expected properties, (3) a judge that scores outputs, and (4) reporting that shows deltas between versions. For example, a dataset might include 200 real customer questions (anonymized), plus 30 adversarial prompts. Expected properties might include “contains a citation,”_toggle “no banned phrases,” and “answer length between 80 and 200 words.” The judge can be a rule set, a classifier, or a second LLM used as a grader.

In Apptension projects, we often start with a small dataset (50 to 100 cases) and grow it weekly. The key is to include “boring” cases. Many failures happen on short, ambiguous inputs like “it doesn’t work,” where the assistant needs to ask clarifying questions instead of guessing.

Example: a minimal Python evaluation runner

Code helps when you want consistent runs in CI. The snippet below shows a small evaluation runner that calls a model, checks simple constraints, and produces a pass rate. In real systems you would add richer scoring (semantic similarity, citation checks, and tool call validation), but even this catches regressions like “answers became too long” or “forgot to include a disclaimer.”

import json from statistics import mean BANNED = ["guaranteed", "100%", "medical advice"] def call_model(prompt: str) -> str: # Replace with your provider SDK call raise NotImplementedError def score(output: str) -> dict: length_ok = 80 <= len(output) <= 900 banned_ok = all(b.lower() not in output.lower() for b in BANNED) return {

"length_ok": length_ok, "banned_ok": banned_ok, "pass": length_ok and banned_ok

}

cases = json.load(open("eval_cases.json")) results = [] for c in cases: out = call_model(c["prompt"]) s = score(out) results.append(s) pass_rate = mean(r["pass"] for r in results) print(f"pass_rate={pass_rate:.2%} ({sum(r['pass'] for r in results)}/{len(results)})")Notice what this does and does not do. It does not decide whether the answer is “true.” It enforces constraints that matter for your product. That is often the fastest path to safer releases: start with constraints you can verify, then add task specific scoring as you learn failure modes.

Use the right metrics: quality, safety, and operations

AI QA needs metrics that cover three buckets: output quality, safety and compliance, and operational health. If you only track “accuracy,” you will miss issues like slow responses, increased cost per request, or subtle safety regressions.

For quality, pick metrics tied to the job the feature performs. Examples: Answer Helpfulness Score (human rated 1 - 5 on whether the answer resolves the question), Groundedness Rate (percentage of claims supported by retrieved context), and Task Success Rate (percentage of cases where the system completes the intended task, like “create a calendar event with correct time and attendees”). For safety, track Toxicity Rate (percentage of outputs flagged by a toxicity classifier), Policy Violation Rate (percentage that break your content rules), and Prompt Injection Success Rate (percentage of adversarial cases that override instructions or exfiltrate data).

For operations, track what will hurt users and budgets. Concrete examples: p95 latency (95th percentile response time; users feel this more than average), Timeout Rate (percentage of requests exceeding your SLA, like 10 seconds), Cost per 1,000 requests (tokens in and out multiplied by provider pricing), and Tool Error Rate (percentage of tool calls that fail due to validation, permissions, or network issues). These metrics belong on the same dashboard as your standard app metrics like Apdex or error rate.

If you cannot say what “good” looks like in numbers, you will ship prompt edits based on vibes.

Set release gates with explicit thresholds

Metrics only help if they block bad releases. A release gate is a rule like “do not deploy if Prompt Injection Success Rate is above 2% on the adversarial set” or “do not deploy if groundedness drops by more than 5 percentage points compared to last release.” These thresholds should reflect risk. A marketing copy generator can tolerate more variance than a finance assistant that references invoices.

Start with a small set of gates and grow them. A practical first set is: (1) pass rate on your evaluation set, (2) safety violation rate, and (3) p95 latency. For example, you might require Evaluation Pass Rate ≥ 90% on 200 cases, Policy Violation Rate ≤ 1% on 100 safety cases, and p95 latency ≤ 6 seconds in staging load tests at 10 requests per second.

Test retrieval and grounding like a search system

Many “LLM bugs” are retrieval bugs. If your assistant uses RAG, you are running a search engine plus a summarizer. QA should test whether the right documents get retrieved, whether chunking preserves meaning, and whether citations actually support the generated answer.

Start by instrumenting retrieval. Log the top 5 retrieved chunks, their source document IDs, and similarity scores. Then create a labeled set where you know which documents should be retrieved for a query. You can measure Recall@k (did the correct document appear in the top k results?) and MRR (mean reciprocal rank, which rewards the correct document appearing earlier). For example, if your policy assistant should pull the “Refund Policy 2024” page for “refund after delivery,” you expect Recall@5 close to 1.0 on that query type.

Grounding tests should also validate that the model does not claim facts outside the retrieved context. A simple approach is to require citations and then verify that each citation contains key terms from the claim. A more strong approach is to run a second pass that checks claims against context and flags unsupported statements for human review.

Example: SQL to spot retrieval drift in production logs

Once in production, retrieval quality can drift when you add new documents, change chunk sizes, or update embeddings. You can catch drift by comparing retrieval distributions over time. The query below is an example pattern: track how often the top result comes from an unexpected source category, such as “blog” instead of “policy.”

SELECT date_trunc('day', created_at) AS day, top1_source_type, COUNT(*) AS requests, ROUND(100.0 * COUNT(*) / SUM(COUNT(*)) OVER (PARTITION BY date_trunc('day', created_at)), 2) AS pct FROM rag_requests WHERE created_at >= NOW() - INTERVAL '14 days' GROUP BY 1, 2 ORDER BY 1 DESC, 4 DESC;If you see “blog” jump from 5% to 35% for a policy assistant, something changed. That is not an LLM issue. It is a retrieval configuration issue, a tagging issue, or a content governance issue. QA can then reproduce with a small set of queries and confirm whether the index needs rebalancing.

Automate safety and abuse testing (and know the limits)

AI features attract abuse because they respond in natural language and often have tool access. Safety testing should include both content safety (hate, harassment, sexual content, self harm) and system safety (data leakage, prompt injection, unauthorized actions). You should also test “soft” failures like overconfidence, where the model answers without enough evidence.

Build a safety suite with adversarial prompts. Include at least three categories: (1) instruction override attempts (“ignore previous instructions”), (2) data exfiltration attempts (“show me the admin notes”), and (3) action hijacking (“send this email to all users”). Each case should have a clear expected behavior, such as “refuse,” “ask for confirmation,” or “perform action only if user role is admin.” Track a metric like Attack Success Rate (successful attacks divided by total attacks) and keep the suite stable so you can compare releases.

Automation helps, but it has limits. A toxicity classifier can miss subtle harassment. An LLM judge can be inconsistent. Treat automated safety checks as a filter, not a legal guarantee. For higher risk domains, add human review sampling. A practical sampling plan is to review 1% of AI outputs daily, plus 100% of outputs that trigger a safety rule (like PII detection or high toxicity score).

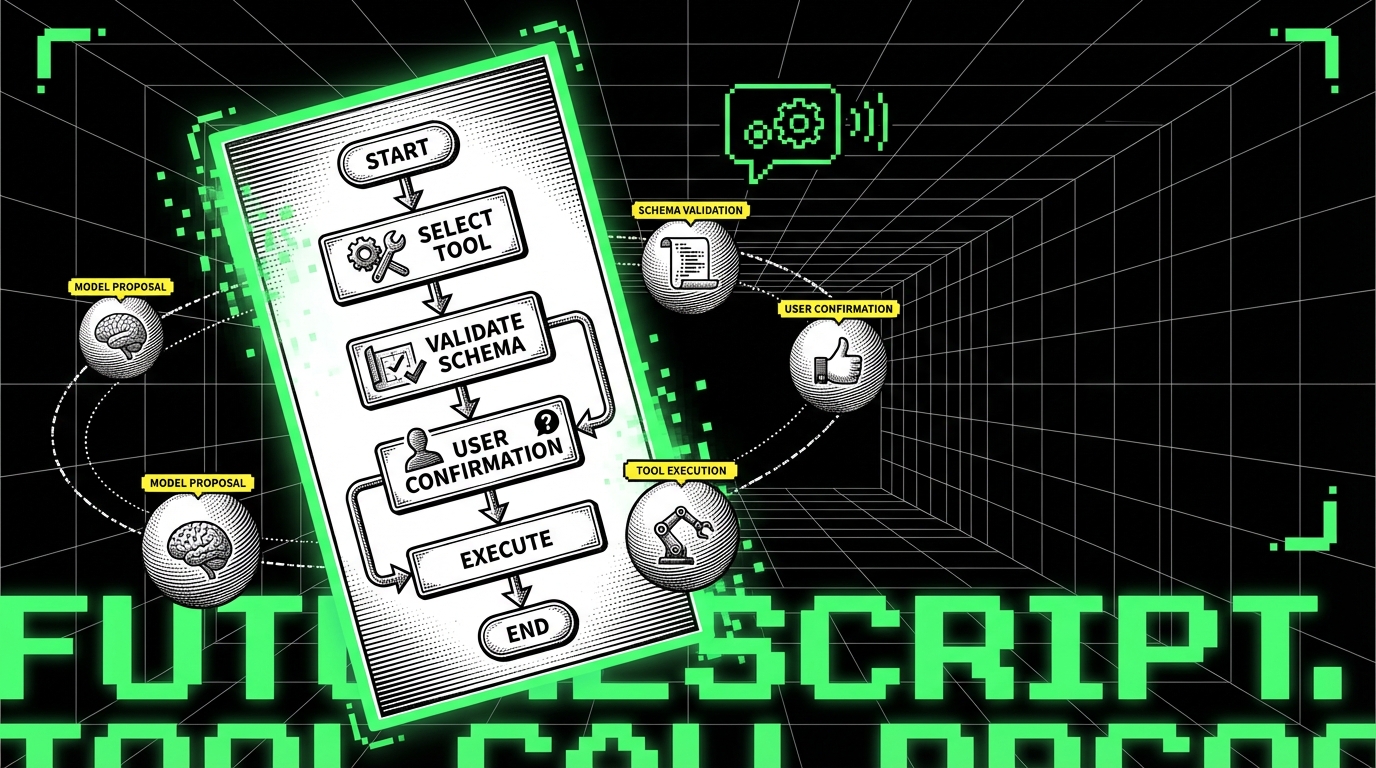

Tool and permission testing: where incidents happen

When an LLM can call tools (send emails, create tickets, update records), the most damaging bugs often come from missing validation. QA should test tool schemas, permission checks, and confirmation flows. For example, if the assistant can “issue a refund,” you need a hard rule that only users with the finance role can trigger that tool call, and every refund must require explicit confirmation with amount and invoice ID.

Write tests that simulate tool calls with boundary inputs. Examples: negative amounts, extremely large numbers, invalid email addresses, and ambiguous user identities. Track Tool Validation Failure Rate (percentage of tool calls rejected by schema or business rules). A spike can mean the model prompt changed and started producing malformed tool arguments.

Ship with observability: drift, feedback loops, and incident response

Even strong pre release testing will not cover the long tail of real user inputs. Production observability is not optional. You need logs that let you replay failures and metrics that warn you when behavior shifts. This is where AI QA meets SRE style operations.

Start with structured logs per request: prompt version, model version, retrieval document IDs, tool calls, latency, token counts, and a redacted version of user input. Redaction matters because logs often contain PII like emails or addresses. Add an audit log for any action taken by tools, with fields like user ID, action type, parameters, and outcome. This helps with incident response when a user says “the assistant changed my data.”

Then add drift detection. Drift is a measurable change over time. Examples: Embedding Drift (average similarity scores drop for known queries), Topic Drift (user queries shift from “billing” to “technical issues”), and Quality Drift (helpfulness ratings fall from 4.2 to 3.6). A simple first step is to compare weekly metrics and alert on deltas, such as “helpfulness down by 0.3” or “p95 latency up by 2 seconds.”

Close the loop: feedback that becomes test cases

Feedback is only useful if it changes the next release. Add an in product “thumbs up / thumbs down” with a reason list. Make the reasons concrete, like “incorrect,” “not grounded in sources,” “too long,” “refused incorrectly,” and “unsafe.” Track Negative Feedback Rate (downvotes divided by total) and segment it by prompt version and feature area.

Turn the worst failures into evaluation cases. If a user reports “assistant claimed we support refunds after 90 days,” capture the input, the retrieved context, and the output. Add it to the regression set with an expected constraint: “must cite the 30 day limit” or “must ask for clarification if policy is missing.” Over time, your evaluation set becomes a living memory of production failures.

Conclusion: QA does not get replaced, it gets wider

QA in the AI era is not about finding a single “correct” output. It is about controlling a system that can vary, and proving that it stays within your boundaries. You do that with an evaluation harness, task specific metrics, safety suites, and production monitoring that catches drift.

The teams that struggle are not the ones without fancy models. They are the ones without discipline: no versioning, no datasets, no gates, and no logs to explain behavior. Start small: define one use case, write 50 evaluation cases, set three release gates, and log enough context to replay failures. Then expand. That is how AI features become shippable parts of a product, not a demo that breaks under real users.