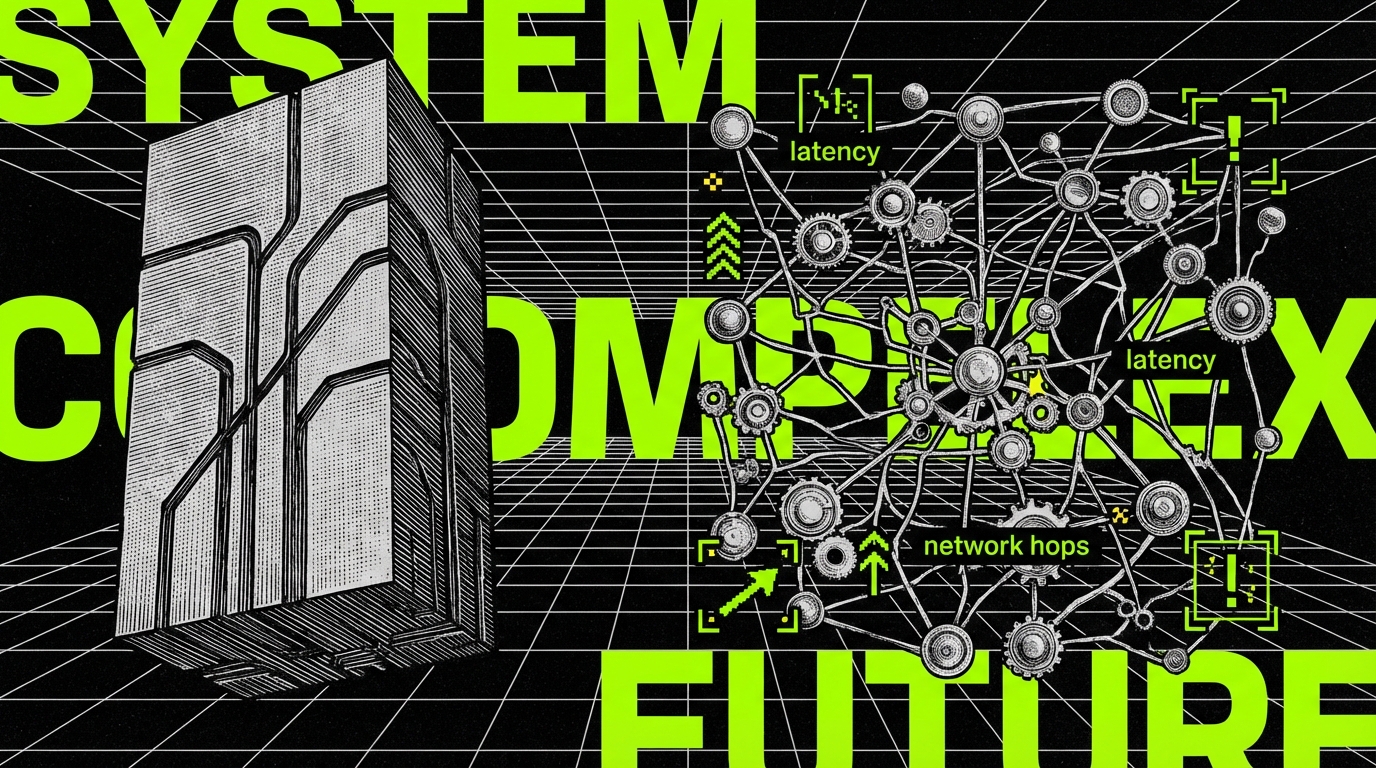

SaaS performance problems rarely come from one slow function. They come from a chain: a chatty API, a database that does too much, a queue that backs up, a cache that lies, and a deploy that changes traffic patterns. Microservices can help, but they also add more moving parts. That trade-off is where most teams get stuck.

At Apptension we have seen both outcomes. On some products, splitting a monolith reduced tail latency because teams could isolate hot paths and scale them without scaling everything else. On other products, an early microservices split made performance worse because network calls replaced in-process calls and nobody had end to end tracing. The architecture did not fail; the execution did.

This article focuses on concrete actions. You will see what to measure, what to split, and how to keep p95 and p99 latencies stable as the system grows. You will also see where microservices can waste time and money if the service boundaries are wrong.

Start with performance goals, not service boundaries

Microservices are a tool, not a goal. If you cannot state your performance targets, you cannot tell if the change helped. Start with a small set of metrics that match user experience and cost. For most SaaS apps, that means request latency, error rate, throughput, and infrastructure spend per request.

Define targets per endpoint, not just for the whole API. A dashboard that loads in 1.2 seconds can still feel slow if one widget blocks the entire view. Also define tail targets. p50 hides pain; p95 and p99 show it. If you do not track tails, microservices can look “fine” while users complain.

In delivery work, we usually begin by writing down a few numbers that the team can repeat from memory. Examples that work in practice include p95 under 300 ms for authenticated reads, p95 under 800 ms for complex search, and error rate under 0.1% for core flows. The exact numbers depend on the product, but the habit matters more than the threshold.

If you cannot explain which user action maps to a latency chart, you are not measuring performance. You are collecting numbers.

When you have targets, you can decide if microservices are even necessary. Many SaaS apps get large wins from simpler changes first: indexing, query shaping, caching, and async processing. Microservices make sense when you need independent scaling, different runtime constraints, or isolated failure domains.

- Good reasons: one feature drives 70% of CPU, one integration causes timeouts, or one team needs a different release cadence.

- Weak reasons: “we want microservices,” “our competitors have them,” or “it will be faster later.”

- Hard constraint reasons: regulated data zones, tenant isolation requirements, or separate availability targets for billing vs the app.

Pick boundaries that reduce contention and network chatter

Performance gains from microservices often come from reducing contention. In a monolith, one noisy feature can starve others of CPU, DB connections, or locks. Splitting that feature into a service lets you scale and tune it separately. But if you split along the wrong boundary, you replace contention with network latency and retries.

A practical rule: split around data ownership and workload shape. If two modules fight over the same tables, splitting them without fixing the data model usually increases latency. If one module has spiky traffic and another is steady, splitting can reduce both cost and tail latency.

Use bounded contexts and “one writer” data ownership

Bounded contexts are not a theory exercise. They are a way to stop services from sharing tables and creating cross-service joins. A service should be the only writer for its core tables. Other services can read via APIs, read models, or replicated projections.

When teams ignore this, they often end up with “microservices” that still share a database. That setup keeps coupling but adds network hops. It also makes performance tuning harder because you cannot tell which service caused a slow query. If you must start with a shared DB, treat it as a temporary stage with an explicit migration plan.

Prefer coarse-grained APIs over chatty call graphs

Chatty APIs kill p95. A request that triggers 10 service calls might be fine at p50, then collapse at peak traffic when retries start. Design endpoints that return what the caller needs in one call, even if the response is larger. Use pagination and field selection to keep payloads reasonable.

In SaaS dashboards, we often see a pattern where the UI asks for counts, lists, and status flags separately. A backend-for-frontend (BFF) service can aggregate these calls and cache results close to the UI. It is not about “GraphQL vs REST” as a debate. It is about reducing the number of network round trips on the critical path.

Control latency with caching, async work, and backpressure

Microservices add network hops, so you need deliberate latency control. The core patterns are simple: cache stable reads, move non-critical work off the request thread, and apply backpressure before the system melts down. Without these, microservices often shift bottlenecks instead of removing them.

At Apptension we commonly implement a mix of Redis caching, queue-based background jobs, and strict timeouts. The goal is not “fast at any cost.” The goal is predictable performance under load. Predictability matters more than a benchmark number that only appears in staging.

Caching: pick what to cache and how to expire it

Cache the things that are read often and change rarely. Examples include feature flags, pricing plans, permissions, and reference data. Cache keys should include tenant identifiers and versioning where needed. If you do not include tenant context, you will ship a data leak.

Expiration is where teams get hurt. A long TTL improves hit rate but increases staleness risk. A short TTL reduces staleness but can cause thundering herds. Use request coalescing and stale-while-revalidate for popular keys. Also measure cache hit rate and the latency difference between hit and miss.

import Redis from "ioredis";

const redis = new Redis(process.env.REDIS_URL);

type CacheResult = {

value: T;source: "cache" | "origin"

};

export async function getOrSetJson(key: string, ttlSeconds: number, fetcher:

() => Promise

): Promise > {

const cached = await redis.get(key);

if (cached) {

return {

value: JSON.parse(cached) as T,

source: "cache"

};

}

const value =

await fetcher(); // Keep payloads small. Large objects increase Redis latency and memory. await redis.set(key, JSON.stringify(value), "EX", ttlSeconds); return { value, source: "origin" };

}Notice what is missing: no silent failures. If Redis is down, you should decide whether to fail open (skip cache) or fail closed (block). For most SaaS reads, failing open is safer for availability, but it can spike DB load. Make that choice explicit per endpoint.

Async processing: move work off the critical path

Many SaaS requests do too much. They write data, send emails, call third party APIs, and rebuild search indexes in one synchronous flow. Microservices make it tempting to add even more calls. Instead, keep the request small: validate, write the core state change, and enqueue the rest.

Queues also give you a place to apply backpressure. If a downstream system slows down, the queue grows instead of blocking user requests. But you must set limits, retries, and dead-letter handling. A queue without limits is just a delayed outage.

import {

Queue

} from "bullmq";

const queue = new Queue("outbox", {

connection: {

host: "redis"

}

});

export async function publishDomainEvent(event: {

type: string;tenantId: string;payload: unknown;

}) { // Keep job payload small. Store large blobs in object storage. await queue.add(event.type, event, { attempts: 5, backoff: { type: "exponential", delay: 500 }, removeOnComplete: 1000, removeOnFail: 5000, });

}This pattern works best with an outbox table so you do not lose events when a request commits but the publish step fails. In practice, we often implement “transaction writes outbox row” and a worker that publishes events. It is boring, and it prevents a class of data inconsistencies that show up as performance issues later.

Backpressure and timeouts: stop retry storms

Retries can turn a slow dependency into a full outage. Each retry adds load, increases queue time, and pushes p99 up. Set timeouts per hop and cap retries. Prefer hedged requests only for idempotent reads and only when you can measure the effect.

Circuit breakers help, but only when paired with good fallbacks. A breaker that opens and returns 500 for everything is just a different failure mode. A better fallback might return cached data, partial results, or a “try again later” response that the UI can handle.

- Set per-request deadlines and pass them downstream.

- Use bulkheads: separate connection pools for critical dependencies.

- Reject early when queues exceed a threshold.

- Make retries visible in metrics, not hidden in logs.

Data patterns that keep microservices fast

Data is where microservices either shine or become slow. The slow version is obvious: service A calls service B, which calls service C, each doing its own DB query, then the caller stitches results together. This creates long call chains and multiplies tail latency.

The fast version accepts duplication. You keep a source of truth, but you also build read models for common queries. You move from cross-service joins to projections and denormalized views. You also avoid distributed transactions in the hot path.

CQRS and read models for SaaS dashboards

SaaS dashboards often need “counts by status,” “recent activity,” and “top entities” for a tenant. These queries can be expensive if computed from normalized tables on every request. A read model can precompute these aggregates and update them from events.

This works well when users accept slight delays, like 1 - 5 seconds, in analytics tiles. It works poorly when the UI needs strict read-after-write consistency for the same user action. In that case, you may need a hybrid: read model for most tiles, direct read for the just-changed entity.

Saga patterns for multi-step workflows

If a workflow spans billing, provisioning, and notifications, a distributed transaction is a trap. Two-phase commit adds latency and complexity, and it still fails in messy ways. A saga coordinates steps with compensating actions. It is not “free,” but it keeps each service simple and keeps failures contained.

Performance-wise, sagas help because they turn one long request into a series of small steps. Users get a quick acknowledgement and then see progress. The trade-off is product complexity: you need status tracking, idempotency, and clear UX for “pending” states.

- Write the command and initial state (fast DB write).

- Publish an event to start provisioning (async).

- Provisioning service performs work and emits success or failure.

- Billing service charges or refunds based on saga state.

- UI polls or subscribes to status updates.

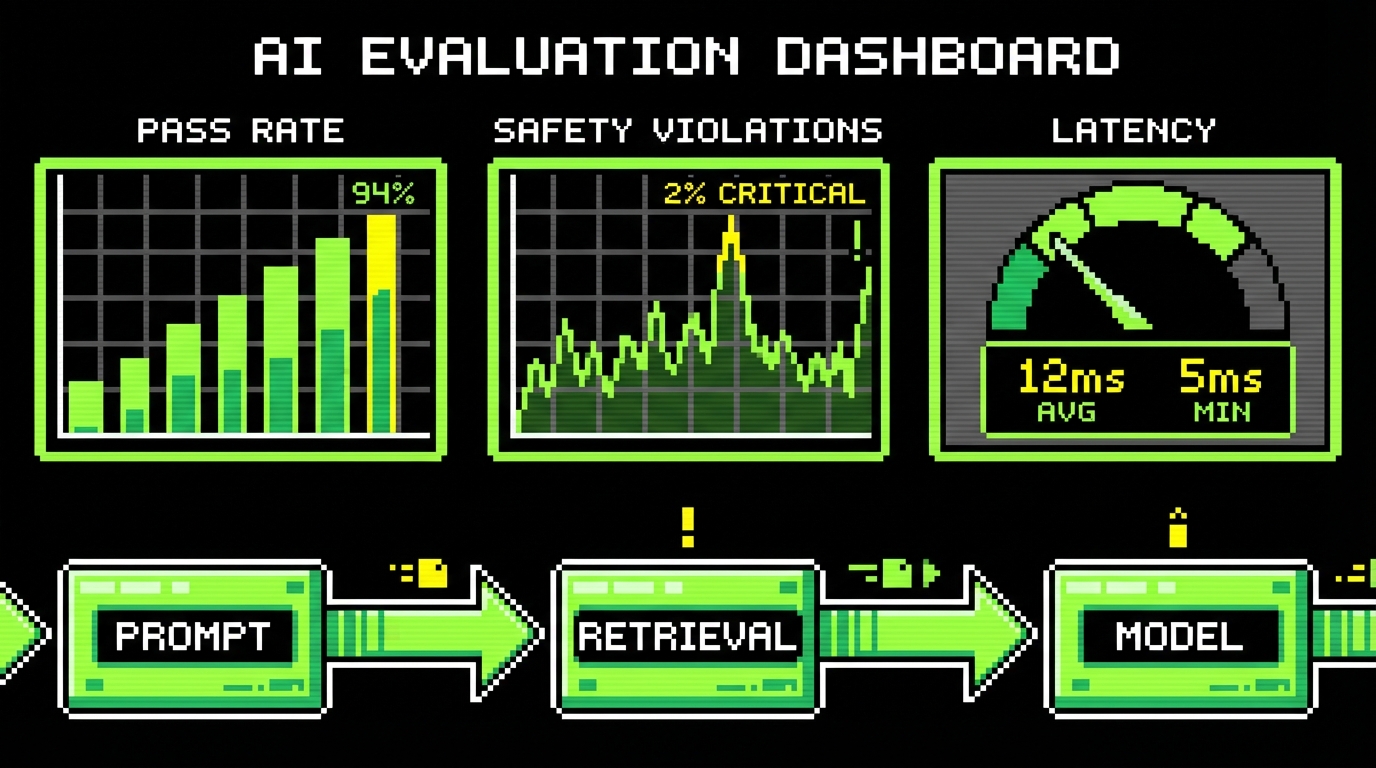

Observability: you cannot tune what you cannot see

Microservices without observability are guesswork. You need to answer basic questions quickly: which service is slow, which dependency is slow, and what changed in the last deploy. Logs alone rarely get you there because the problem is across services and time.

Set up tracing, metrics, and structured logs from day one of a split. In our projects, the first performance win often comes from seeing the call graph and deleting unnecessary hops. The second win comes from catching slow queries and N+1 patterns that were invisible before.

Distributed tracing with OpenTelemetry

Use OpenTelemetry to propagate trace context across HTTP and messaging. Instrument your HTTP server, client, DB driver, and queue consumer. Then standardize span names and attributes, such as tenant.id, http.route, and db.operation. Without consistent attributes, traces are hard to search.

Sampling is a practical concern. Full sampling in production can be expensive. Start with head sampling for baseline visibility, then add tail sampling for slow traces and errors. Tail sampling is where you catch p99 behavior without storing everything.

import {

NodeSDK

} from "@opentelemetry/sdk-node";

import {

getNodeAutoInstrumentations

} from "@opentelemetry/auto-instrumentations-node";

import {

Resource

} from "@opentelemetry/resources";

import {

SemanticResourceAttributes

} from "@opentelemetry/semantic-conventions";

const sdk = new NodeSDK({

resource: new Resource({

[SemanticResourceAttributes.SERVICE_NAME]: "orders-service",

"deployment.environment": process.env.NODE_ENV ?? "dev",

}),

instrumentations: [getNodeAutoInstrumentations()],

});

sdk.start();Do not stop at “we have tracing.” Add SLO dashboards that show p95 and p99 by route and by tenant tier. When a single tenant drives load, you want to see it. That is common in B2B SaaS, and it changes scaling decisions.

Load testing and profiling in a microservices world

Microservices change how you test. A single-service benchmark can be misleading because the bottleneck might sit in an upstream gateway or a shared database. Run end to end load tests that mimic real user flows, then drill down into per-service metrics.

Tools that work well include k6 for load generation, profiling with pprof (Go) or clinic.js (Node), and DB query analysis with built in Postgres stats. The key is repeatability: run the same test after each major change. If you cannot reproduce a regression, you cannot fix it.

- Test p95 and p99, not just average latency.

- Include cache warm and cache cold scenarios.

- Simulate downstream slowness to validate timeouts and breakers.

- Record resource usage per request: CPU ms, DB time, and network time.

Deployment and scaling strategies that protect p99

Performance problems often appear during deploys. A new version changes query patterns, invalidates caches, or increases payload sizes. In microservices, you deploy more often, so you need safer defaults. Otherwise p99 becomes a deploy artifact, not a product metric.

Scaling is also different. Autoscaling a single service can help, but only if the bottleneck is inside that service. If the DB is the bottleneck, scaling stateless services just increases pressure. You need capacity planning across the whole request path.

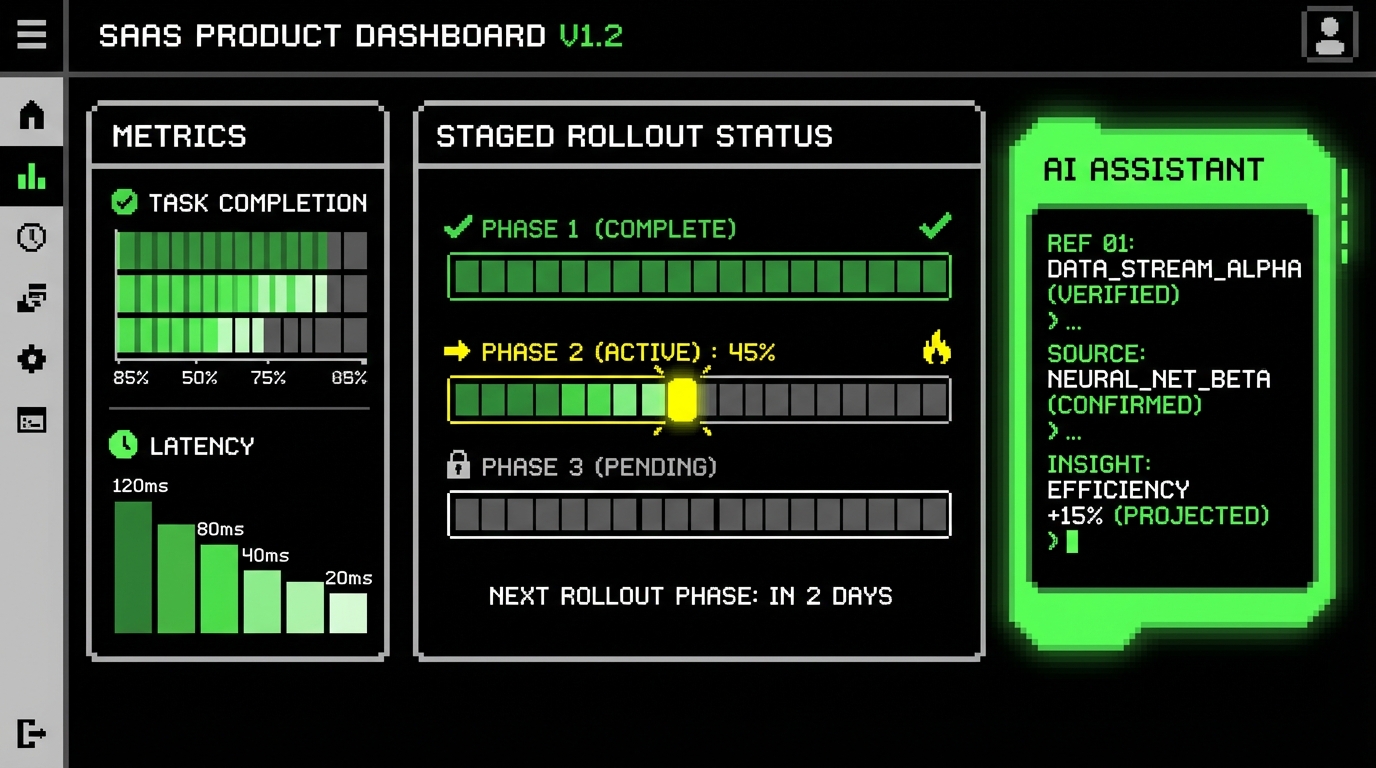

Progressive delivery: canary, blue-green, and feature flags

Canary deploys reduce risk by shifting a small percentage of traffic to a new version. Blue-green deploys reduce downtime but can still cause cache cold starts. Feature flags help you decouple deploy from release, but they can add branching and complexity if unmanaged.

For performance, canaries are useful because you can compare latency distributions between versions. Track p95 and p99 per version, not just global. If the new version increases DB time by 20%, you want to know before it hits all tenants.

Most “microservices performance regressions” are deploy regressions that nobody measured at the version level.

Autoscaling with HPA and queue depth signals

CPU-based autoscaling is a start, but SaaS workloads often bottleneck on IO, DB connections, or queue backlog. Add scaling signals that match the service role. For a worker service, queue depth and job age are better than CPU. For an API, request rate and latency can be more stable triggers.

Also set sane limits. If a bug causes runaway enqueues, autoscaling can multiply cost while the system still fails. Put caps on replica counts and add alerting when you hit them. A capped failure is easier to debug than an uncapped bill.

- Set resource requests and limits so the scheduler behaves predictably.

- Scale workers on queue depth and max job age.

- Scale APIs on concurrency or latency, not only CPU.

- Protect shared dependencies with connection pool limits.

Where microservices hurt performance (and what to do instead)

Microservices can make performance worse in predictable ways. The most common is over-splitting: too many services, each with a tiny responsibility, connected by synchronous calls. That design adds latency and increases the chance of partial failure. It also makes local development slow, which delays fixes.

Another common issue is inconsistent tech choices. If every service uses a different framework, logging format, and deployment pipeline, you lose operational speed. The performance impact is indirect but real: slower debugging and slower iteration. Standardization is not about taste; it is about reducing time-to-fix.

When a modular monolith is the better first step

If your main problem is slow queries or unbounded background work, a modular monolith can be faster to improve. You get clear module boundaries, one deployment unit, and in-process calls. You can still enforce data ownership and build read models. You can also extract services later when the boundary is proven.

We have used this path on early-stage SaaS builds where the domain was still changing weekly. The performance work focused on profiling, DB indexes, and caching. Once traffic patterns stabilized, we extracted one or two hotspots into services. That sequence reduced risk and kept p95 stable during product churn.

Anti-pattern checklist

These anti-patterns show up in performance incidents more often than exotic bugs. They are easy to miss during design because each one looks “reasonable” in isolation. Treat them as review items for every new service and endpoint.

- Synchronous fan-out calls from one request to many services.

- Shared database with cross-service joins in production queries.

- Retries without deadlines and without jitter.

- Queue consumers without idempotency and with unlimited retries.

- Cache keys without tenant scope or versioning.

- Missing per-route p95 and p99 metrics.

If you recognize several of these in your system, do not panic. Pick one critical user flow and fix it end to end. The performance improvement from removing one fan-out chain can exceed the improvement from months of “general optimization.”

Conclusion: make microservices earn their keep

Microservices can improve SaaS performance when they reduce contention, isolate hotspots, and let you scale the right parts of the system. They can also degrade performance when they create chatty call graphs, shared data coupling, and retry storms. The difference is not the diagram. It is the operational discipline.

Start with measurable goals. Design boundaries around data ownership and workload shape. Keep critical paths short with caching and async work. Add backpressure and strict timeouts. Invest in tracing and version-level deploy metrics so you can see regressions before users do.

If you are not ready for that discipline, a modular monolith can be the better move. It gives you most of the design benefits with fewer performance traps. When you later extract services, you will do it with evidence from production, not hope.