SaaS teams do not get “done.” You ship, you learn, you fix, and you repeat. That loop runs under pressure: production incidents, customer requests, roadmap promises, and a codebase that keeps growing. Agile helps, but only if you pick a framework that matches how your product actually changes.

In Apptension delivery work (including our own SaaS product Teamdeck), the pattern is consistent. Teams that treat Agile as a meeting schedule slow down. Teams that treat it as a set of constraints for decision making speed up. The difference shows up in cycle time, defect rates, and how often releases cause stress.

This article breaks down the frameworks that work well for SaaS, what they cost, and how to implement them with concrete tools and metrics. You will see where each framework fails, because every one of them does under the wrong conditions.

What “Agile” means in SaaS (and what it does not)

SaaS has two hard constraints. First, you run a live system. Every change competes with reliability work, and reliability work is never finished. Second, you learn from real usage data, not from a one time launch, so you need short feedback loops that do not break the product.

Agile frameworks are just ways to manage those constraints. They define how you slice work, how you decide priorities, and how you limit work in progress so you can finish. If your framework does not change those behaviors, it is not doing anything useful.

What Agile does not mean: “we can change everything at any time.” In SaaS, constant priority churn is a tax. It increases context switching, breaks forecasting, and often leads to half built features that never ship. The best teams change direction, but they do it with explicit rules and visible trade offs.

Core SaaS constraints that shape your framework choice

Before you choose Scrum or Kanban, name the constraints you cannot negotiate. For most SaaS products, they look like: on call load, release risk, compliance requirements, and the number of dependencies between teams. Those constraints decide whether you need strict timeboxes, strict WIP limits, or strict engineering practices.

At Apptension, we often start engagements by mapping constraints to workflow policies. For example, if a product has weekly incident spikes, we add a visible capacity budget for reliability. If a product has many stakeholders, we add a rule for decision ownership so “alignment” does not become a blocker.

- Live operations: incidents and support work will interrupt plans unless you reserve capacity.

- Feedback loops: you need fast measurement (events, funnels, churn signals) to avoid opinion driven roadmaps.

- Risk management: releases need guardrails (feature flags, canaries, rollback paths).

- Multi tenancy and data: schema changes and migrations must be planned as first class work.

Scrum for SaaS: predictable cadence, predictable failure modes

Scrum fits SaaS when you need a steady cadence and a clear planning rhythm. Two week sprints work well for teams that ship frequently but still need coordination across design, product, and engineering. The sprint boundary forces prioritization and creates a predictable moment to review outcomes.

Scrum fails when you treat the sprint plan as a contract. SaaS work includes unknowns: performance regressions, third party outages, and customer escalations. If your team “protects the sprint” by ignoring those, production suffers. If your team constantly breaks the sprint, planning becomes theater.

In practice, Scrum works best when you set explicit policies for interrupts and when you keep sprint scope small enough to absorb surprises. That means fewer parallel initiatives, smaller stories, and a stable definition of done that includes testing and release steps.

How to implement Scrum without turning it into meetings

Start by tightening the work item shape. If stories regularly spill, your backlog items are too large or too vague. Add a rule: a story must be releasable on its own, even if it is behind a feature flag. That rule prevents “big bang” merges and reduces integration risk.

Next, reserve capacity for the work you know will happen. Many SaaS teams undercount support and incident work. A simple policy such as “20% of sprint capacity is reserved for interrupts” makes planning honest. If interrupts are lower, you pull extra backlog items rather than replan mid sprint.

- Keep sprint goals outcome based, not task based (for example, “reduce signup drop off at step 2”).

- Use a strict definition of done: code review, tests, observability updates, and deploy steps.

- Limit sprint backlog to what you can finish with current WIP limits.

- Track spillover rate and treat it as a signal, not a failure.

Scrum metrics that matter in SaaS

Velocity is not useless, but it is easy to game and hard to compare across teams. SaaS teams get more value from flow and quality metrics. You want to know how fast work moves from idea to production, and how often it causes trouble after release.

We usually pair sprint reporting with a small set of operational metrics. That keeps the team honest about the cost of shipping. It also prevents “feature factory” behavior where the team ships volume but increases support load.

- Cycle time: median time from “in progress” to “deployed.”

- Deployment frequency: releases per day or per week.

- Change failure rate: percentage of deploys that cause rollback, hotfix, or incident.

- MTTR: mean time to recover from incidents.

- Spillover rate: percentage of sprint items not finished.

Scrum helps when it makes trade offs visible. It hurts when it hides uncertainty behind story points.

Kanban for SaaS: flow, WIP limits, and operational reality

Kanban fits SaaS when work arrives continuously and priorities shift often. It handles support queues, infrastructure tasks, and product work in one system. Instead of timeboxes, Kanban relies on WIP limits and explicit policies to keep flow stable.

Kanban fails when teams skip the hard part: saying “no” to new work until capacity exists. Without WIP limits, a Kanban board becomes a list. That leads to long cycle times and hidden delays, especially when several items wait on the same reviewer or environment.

When Kanban works, it makes bottlenecks obvious. You can see that code review is the constraint, or that QA is overloaded, or that deployment is too manual. Then you can fix the system, not just push harder.

Designing a Kanban system for product and platform work

A useful Kanban board reflects real states, not aspirational ones. If “In QA” is really “waiting for QA,” name it that way. If deployments happen twice a week, include a “Ready for deploy” column so you can measure queue time. Those details change behavior because they show where time is lost.

For SaaS teams, it helps to split work classes. Incidents should not compete with feature work inside the same WIP limit, because incident response needs a fast lane. A common pattern is to use swimlanes or separate boards with shared capacity rules.

- Standard: planned product work with normal SLA.

- Expedite: production incidents and urgent fixes with strict entry rules.

- Fixed date: compliance deadlines or customer commitments, used sparingly.

- Intangible: refactors and tooling that reduce future cost, tracked explicitly.

Kanban metrics: lead time, throughput, and aging work

Kanban gives you strong forecasting if you measure the right things. Lead time distribution tells you what “normal” looks like and how often you get outliers. Throughput shows how many items you finish per week. Aging work highlights items stuck beyond a threshold so you can intervene early.

In SaaS, aging work is often a symptom of hidden dependencies: waiting for a data migration window, waiting for product copy, or waiting for security review. When you make those waits visible, you can either remove the dependency or plan it as part of the work item.

- Track lead time percentiles (50th, 85th) rather than averages.

- Set an aging threshold (for example, 7 days in progress) and review daily.

- Limit WIP per column, not just per board.

- Use a service level expectation for standard work (for example, 85% done within 10 days).

Shape Up: six week bets for SaaS teams with strong autonomy

Shape Up works well when you want fewer planning cycles and more focus. It uses fixed time (typically six weeks) and variable scope. Teams commit to a “bet” with clear boundaries, then shape the solution during the cycle. That reduces mid cycle negotiation and protects maker time.

Shape Up fails when the organization cannot accept variable scope. If stakeholders expect a fixed list of features by a date, the model breaks. It also struggles when teams have heavy interrupt load, because six weeks of focus is hard to defend without strong operational support.

We have seen Shape Up style cycles work best for SaaS products with a stable platform and a clear product direction. It also helps when you have a small number of senior engineers who can shape work well and avoid over engineering.

Shaping work: from appetite to boundaries

Shaping is the discipline that makes Shape Up possible. You define the problem, set appetite (time budget), and draw boundaries that prevent scope creep. The output is not a detailed backlog. It is a pitch that explains what success looks like and what is out of bounds.

For SaaS, boundaries should include data and migration constraints, rollout approach, and observability requirements. If you skip those, the team will discover them late and burn the cycle on unplanned infrastructure work.

- Appetite: “We will spend up to 6 weeks on this.”

- Non goals: “We will not redesign billing UI in this cycle.”

- Risk notes: “This touches multi tenant permissions, add security review early.”

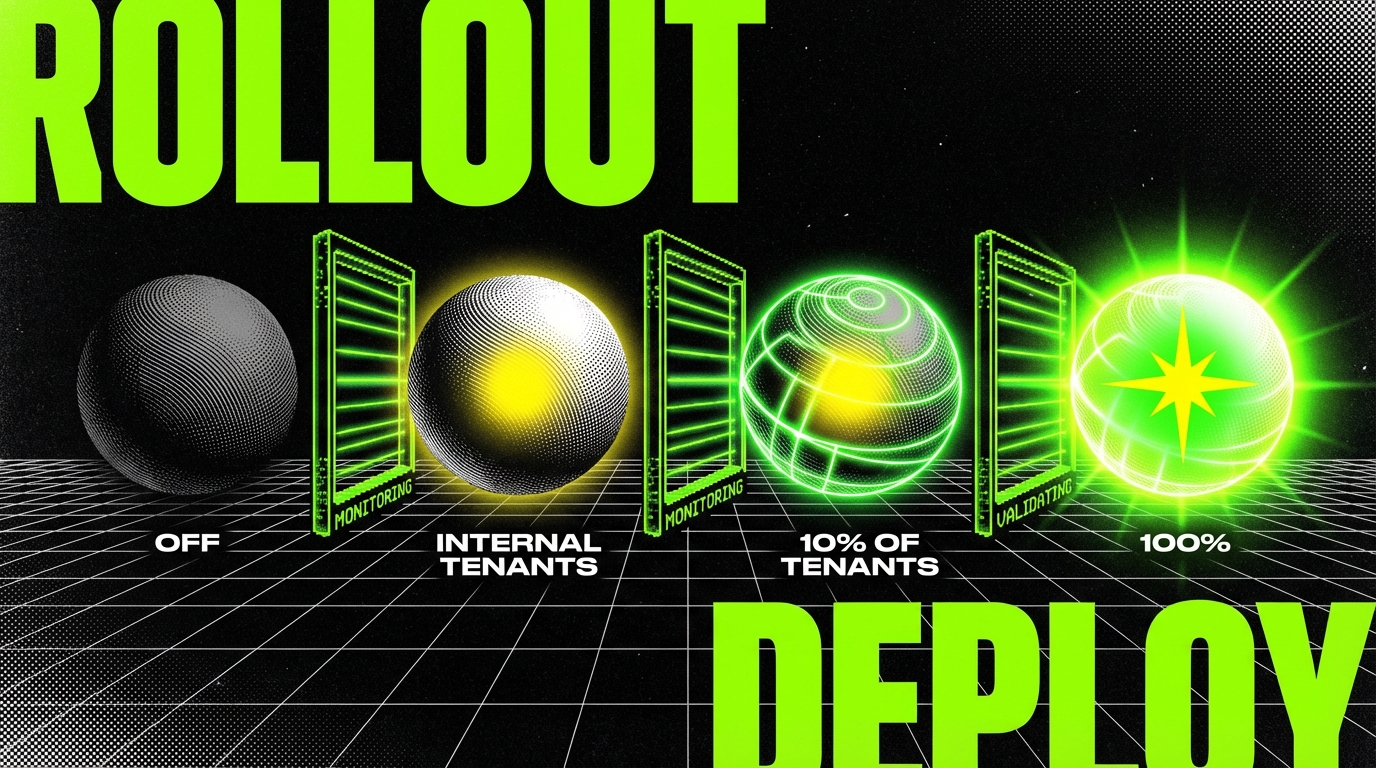

- Rollout plan: “Ship behind a feature flag, enable for internal tenants first.”

Where Shape Up fits in a modern SaaS stack

Shape Up assumes you can ship small slices inside a bet. That pairs well with feature flags, trunk based development, and strong CI. If your release process is manual or your environments are fragile, a six week cycle turns into a long integration phase at the end.

In Apptension projects, we often combine Shape Up bets with a Kanban lane for interrupts. That keeps incident work from poisoning the bet system. It also forces a real conversation about capacity, because the bet only works if you protect it.

Fixed time and variable scope is honest. It forces you to decide what matters when reality shows up.

Extreme Programming (XP): engineering practices that keep SaaS safe

XP is not a planning framework. It is a set of engineering practices that reduce risk and keep feedback fast. In SaaS, XP shines because the cost of defects is high. A bad deploy can break onboarding, billing, or data integrity, and support will feel it within minutes.

XP fails when teams adopt the slogans without the discipline. “We do TDD” can mean “we write some tests sometimes.” Pair programming can turn into constant interruptions if you do not structure it. Continuous integration can become slow and flaky if you do not invest in test speed and environment stability.

When XP works, it makes other frameworks easier. Scrum planning becomes more accurate because stories are smaller and safer. Kanban flow improves because code review and QA queues shrink. Shape Up bets become less risky because you can ship partial work behind flags.

Practical XP subset for SaaS teams

You do not need the full XP catalog to get value. Pick the practices that directly reduce SaaS risk: automated tests, trunk based development, small commits, and refactoring as routine work. Add pair programming selectively, such as for complex migrations or permission logic.

Teamdeck’s product work has repeatedly shown that “small and safe” beats “big and heroic.” Small pull requests reduce review time. Feature flags reduce merge pressure. A fast CI pipeline reduces the temptation to skip tests.

- TDD where it pays: domain logic, billing, permissions, data transformations.

- Contract tests: between services and between frontend and backend APIs.

- Trunk based development: short lived branches, frequent merges.

- Refactoring budget: planned time to reduce complexity, not just “later.”

Code example: feature flags and safe rollout

Feature flags are not a product trick. They are a delivery tool. They let you merge incomplete work, deploy it safely, and control exposure by tenant, user role, or percentage. That reduces long lived branches and makes rollback a config change instead of a hotfix.

The failure mode is flag debt. Flags that never get removed create confusing code paths and test matrices. Add a removal date and track flags as work items. Treat “remove flag” as part of done, not a nice to have.

type TenantId = string;

interface FeatureFlagService {

isEnabled(flag: string, tenantId: TenantId): Promise;

}

class BillingController {

constructor(private flags: FeatureFlagService) {}

async getInvoicePdf(tenantId: TenantId, invoiceId: string) {

const useNewRenderer = await this.flags.isEnabled(

"billing.newPdfRenderer", tenantId);

if (useNewRenderer) {

return this.renderWithNewService(invoiceId);

}

return this.renderWithLegacyService(invoiceId);

}

private async renderWithNewService(invoiceId:

string) { // Call a new internal service, add extra metrics, handle timeouts. return { source: "new", invoiceId }; } private async renderWithLegacyService(invoiceId: string) { return { source: "legacy", invoiceId }; }

}

Dual Track Agile: discovery and delivery without chaos

Dual Track Agile splits work into two tracks: discovery (what to build) and delivery (build and ship). SaaS teams like it because it reduces wasted builds. You test assumptions early with prototypes, user interviews, or data analysis, then feed validated work into delivery.

Dual Track fails when discovery becomes a parallel roadmap that never lands, or when delivery becomes a ticket factory that ignores learning. It also fails when discovery does not produce clear decisions. “We learned a lot” is not a decision. You need a go, no go, or change direction result.

In Apptension MVP and PoC work, Dual Track patterns show up naturally. You might run short discovery spikes to validate onboarding steps, pricing pages, or data import flows, then commit to delivery once you can measure success. The key is to keep discovery lightweight and tied to metrics.

Discovery outputs that actually help delivery

Discovery should produce artifacts that reduce engineering risk. Good outputs: a clear problem statement, acceptance criteria tied to user behavior, and a thin slice plan. Bad outputs: a long backlog of speculative features and a design that assumes perfect data and no edge cases.

For SaaS, discovery should also include operational notes. If a feature changes permissions, define roles and audit needs early. If it changes data models, identify migration steps and backfill needs. Those details decide how long delivery will take.

- Hypothesis: “If we add CSV import mapping, activation rate will rise from X to Y.”

- Success metric: activation within 7 days, trial to paid conversion, churn by cohort.

- Thin slice: smallest flow that can be measured in production.

- Risks: data quality, tenant isolation, rate limits, compliance.

Keeping the tracks connected

The handoff between discovery and delivery is the fragile part. If discovery runs too far ahead, it creates a plan that reality will invalidate. If it runs too close, delivery waits for decisions. A practical balance is to keep discovery one to two iterations ahead, with weekly checkpoints.

Make the connection explicit by sharing the same metrics dashboard and the same definition of done. A delivery item is not done when it is merged. It is done when it is deployed, measured, and stable. That closes the loop and keeps discovery grounded in outcomes.

Discovery without delivery is research. Delivery without discovery is gambling.

DevOps and SRE practices: the framework behind your frameworks

Agile planning does not matter if releases are scary. DevOps and SRE practices reduce that fear by making delivery repeatable and observable. In SaaS, this is not optional. Your customers will notice downtime, slow pages, and broken integrations more than they notice your roadmap slides.

DevOps fails when it becomes a separate team that “handles deployments.” That creates handoffs and delays. It also fails when teams add tools but do not change behavior, such as adding Kubernetes while keeping manual release approvals and no rollback plan.

What works is a small set of shared standards: automated builds, predictable environments, and on call ownership. When the team that ships also gets paged, priorities change. Bugs get fixed faster, and risky changes get smaller.

Minimum delivery pipeline for a SaaS product

You can build a solid pipeline without over engineering it. The goal is to make the safe path the easy path. That means one command to run tests, one pipeline that runs on every merge, and one deployment process that is scripted and repeatable.

For TypeScript heavy stacks (common in Apptension projects), a practical baseline is: lint, typecheck, unit tests, integration tests for critical paths, and a deploy step that tags releases. Add database migration checks if you use tools like Prisma or TypeORM, and fail fast on drift.

- CI runs on every pull request and on main branch merges.

- Build artifacts are immutable and versioned.

- Deployments are automated and idempotent.

- Database migrations run with a clear rollback or forward fix plan.

- Feature flags control exposure and allow quick disable.

Observability and incident response as part of Agile

Agile feedback loops require telemetry. Without logs, metrics, and traces, you are guessing. Instrument the product so you can answer basic questions: did the last deploy increase errors, did it slow down the API, did it change conversion, did it affect a specific tenant.

Incident response also needs structure. A blameless postmortem is useful only if it produces changes: alerts, runbooks, tests, and guardrails. Track incident counts and MTTR over time. If they rise, your delivery speed is not real speed, it is borrowed time.

- Golden signals: latency, traffic, errors, saturation.

- Release markers: annotate deploy times in dashboards.

- Runbooks: steps to diagnose common failures.

- Error budgets: a rule for when to slow feature work to fix reliability.

Conclusion: pick a framework, then build the system around it

No Agile framework will save a SaaS team from unclear priorities, poor engineering hygiene, or invisible operational work. Scrum helps when you need cadence and coordination, but it breaks under constant interrupts unless you plan for them. Kanban helps when work is continuous, but it fails without WIP limits and explicit policies. Shape Up protects focus, but only if the organization accepts variable scope.

XP practices and DevOps habits are the multipliers. They make shipping safer, which makes planning more honest. Dual Track reduces waste, but only if discovery produces decisions tied to measurable outcomes. In Apptension projects, the best results come from mixing: a planning model that matches the business, plus engineering practices that keep the system stable.

If you want a simple next step, do this: measure cycle time and change failure rate for one month, then pick the framework that addresses your biggest constraint. Add one policy that reduces chaos, such as a WIP limit or an interrupt budget. Then repeat. SaaS rewards teams that improve the system, not teams that memorize rituals.