“Flexible SaaS” often gets reduced to one question: can the system handle more users? In practice, it is three questions at once. Can the system handle more traffic, can the team ship without fear, and can the cloud bill stay predictable. If you miss any one of those, growth becomes a support queue.

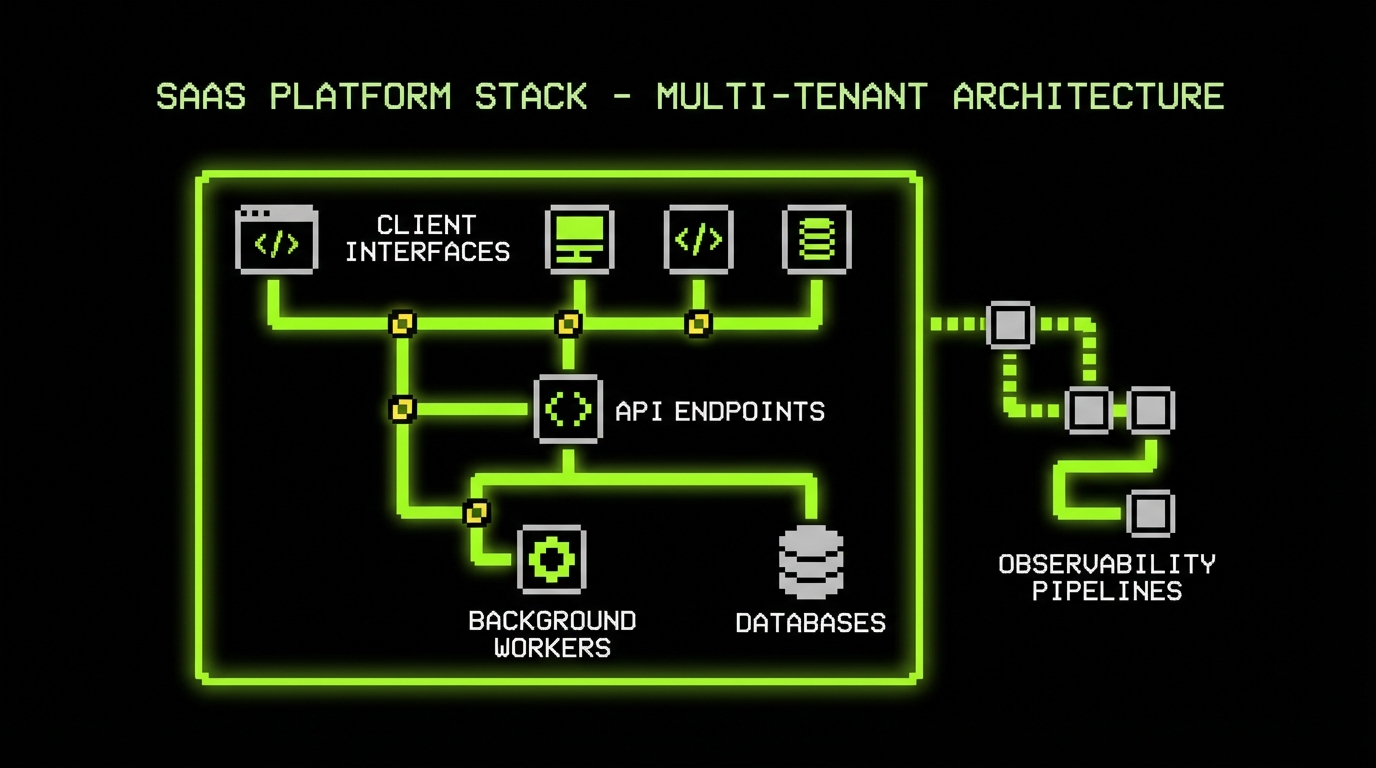

At Apptension we build and run SaaS products that start small and then get real users fast. Some projects have a single tenant at launch and need clean paths to multi tenant later. Others start with enterprise requirements on day one. The patterns below come from what tends to break first: data boundaries, background work, and observability gaps.

This article focuses on tools and implementation details. It also calls out what fails, because most scaling problems come from reasonable shortcuts that never got revisited.

Start with the right scaling target (and write it down)

Scaling is not one thing. A product that needs 99.9% uptime and strict audit logs has a different shape than a product that can tolerate brief delays but must process large batches cheaply. If you do not pick a target, you will “scale” in random directions and still miss the constraint that matters.

We prefer to write a short “scaling brief” before committing to architecture. It is not a long document. It is a set of numbers and failure modes the team agrees to optimize for. This helps avoid building a complex system for a hypothetical future while still protecting the parts that are hard to change later, like data partitioning and identity.

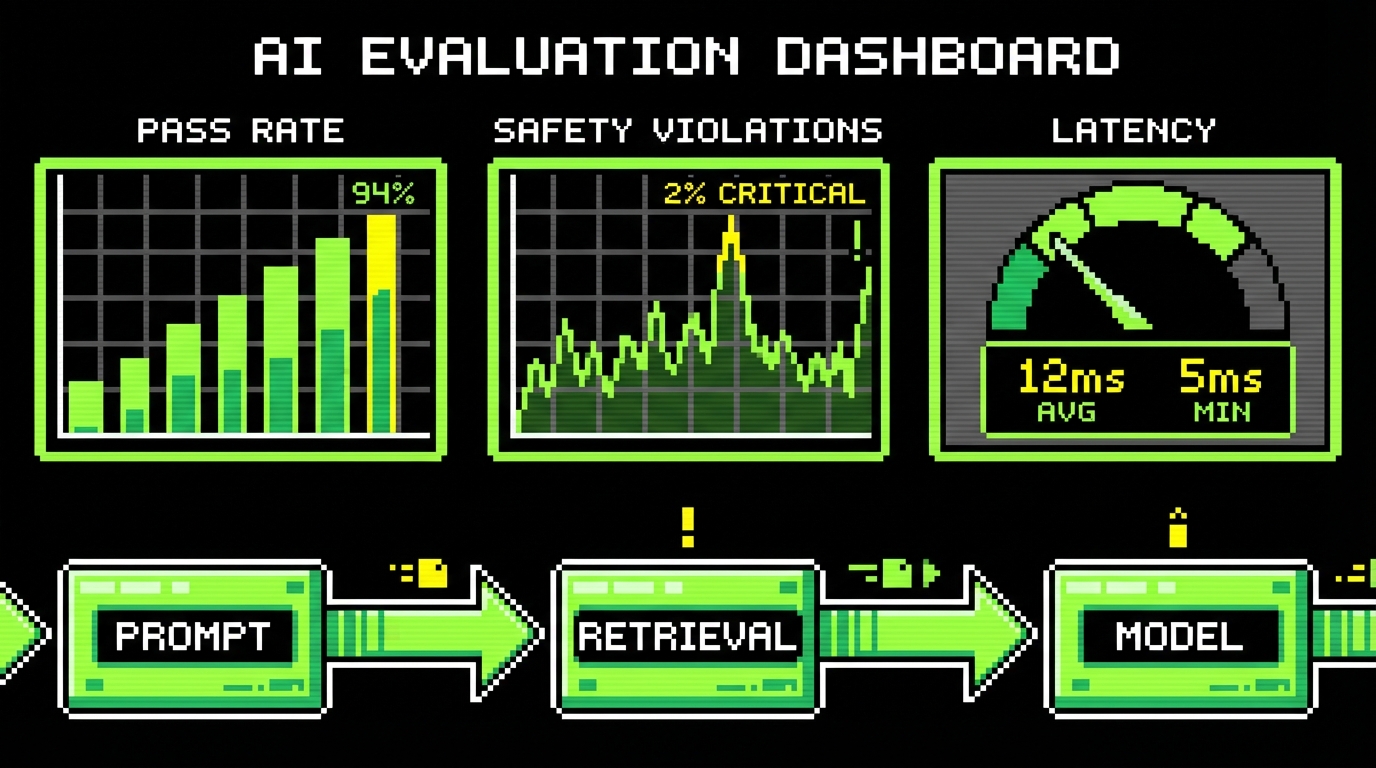

Define SLOs, not vibes

Start with service level objectives (SLOs) that match user pain. “Fast” is not an SLO. “95% of API requests under 300 ms” is. If you cannot measure it, you cannot defend it during a busy week when the backlog is full.

Pick a small set of SLOs and tie them to error budgets. Error budgets stop endless “stability work” from consuming the roadmap, but they also stop endless feature work from destroying reliability. When the error budget is burned, you pause risky changes and fix the system. That is the whole mechanism.

- Latency: p95 and p99 for key endpoints, not global averages.

- Availability: per API surface, not “the app.”

- Freshness: for async pipelines and analytics exports.

- Correctness: rate of failed jobs, duplicate events, or reconciliation mismatches.

Choose a scaling model: vertical, horizontal, or “scale the org”

Many SaaS products scale for a long time by vertical scaling plus a few targeted optimizations. That can be the right choice if the team is small and the traffic pattern is predictable. Horizontal scaling adds operational surface area: load balancing, caches, distributed locks, and noisy neighbor problems.

Also consider the people side. A system that requires deep platform knowledge to deploy will not scale with the team. If only one person can safely touch production, you have a bottleneck that no database index will fix.

Most “scaling” work is removing hidden coupling so more people can ship safely.

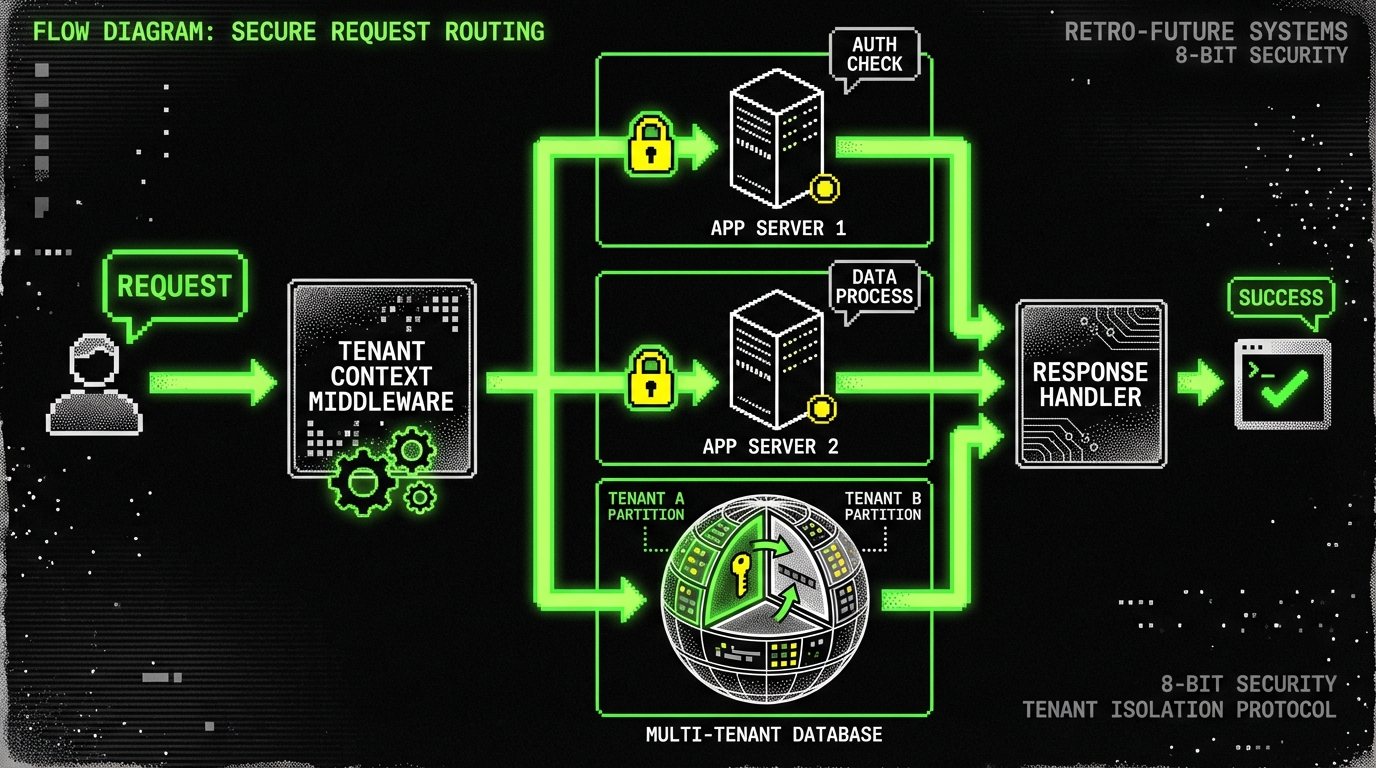

Multi tenancy and identity: decide early, enforce always

Multi tenancy is where SaaS gets sharp edges. The first version often ships with a single tenant mental model, and then the second or third customer forces isolation, billing, and permission rules into places that were never designed for it. Retrofitting tenancy into a large schema is expensive and risky.

We have seen this play out in retail and platform products where the customer list grows quickly. In projects like PetProov, security and trust were core requirements early, so the team treated “who owns this data” as a first class concern. That mindset matters more than any specific framework.

Pick an isolation strategy and accept the tradeoffs

There are three common approaches: shared database with tenant column, separate schema per tenant, or separate database per tenant. Shared tables are simplest to operate and cheapest, but they demand strict query hygiene. Separate databases improve isolation and blast radius, but migrations and analytics get harder.

Do not choose based on ideology. Choose based on compliance needs, expected tenant size variance, and operational maturity. A good rule: if you expect a few tenants to be much larger than the rest, plan a path to isolate “big tenants” later.

- Shared tables: fastest to build; easiest to accidentally leak data if guardrails are weak.

- Schema per tenant: good isolation; more moving parts in migrations.

- DB per tenant: strong isolation; higher ops cost; harder cross tenant reporting.

Enforce tenant context in code, not in PR comments

Relying on “remember to filter by tenant” fails under pressure. Put tenant context into the request lifecycle and make it hard to bypass. In Node.js services we often use request scoped context (AsyncLocalStorage) and wrap database access so tenant filters are applied by default.

Below is a minimal pattern in TypeScript. It is not a full security solution, but it shows the shape: extract tenant ID from auth, store it in context, and require it in repository calls. The goal is to make missing tenant filters a compile time or runtime error, not a code review debate.

import {

AsyncLocalStorage

} from "node:async_hooks";

import type {

Request,

Response,

NextFunction

} from "express";

type TenantContext = {

tenantId: string;userId: string

};

const als = new AsyncLocalStorage();

export function withTenantContext(req: Request, res: Response, next:

NextFunction

) { // Example: resolved from JWT claims or session const tenantId = String(req.headers["x-tenant-id"] || ""); const userId = String(req.headers["x-user-id"] || ""); if (!tenantId || !userId) { res.status(401).json({ error: "Missing tenant or user context" }); return; } als.run({ tenantId, userId }, () => next());

}

export function requireTenant(): TenantContext {

const ctx = als.getStore();

if (!ctx) throw new Error("Tenant context missing");

return ctx;

} // Repository example

export async function listProjects(db: any) {

const {

tenantId

} = requireTenant();

return db.project.findMany({

where: {

tenantId

}

});

}

Data design that scales: schema, indexes, and migrations

Most SaaS performance issues are data issues. Not because the database is “slow,” but because the schema does not match the access patterns. The fix is rarely exotic. It is usually a missing index, a too wide table, or a query that grew from one join to seven.

Plan for change. Your schema will evolve every week early on. If migrations are scary, the team will avoid them and pile complexity into application code. That is how you end up with “temporary” JSON blobs that become permanent.

Model for the reads you actually do

Write down the top 10 queries by business importance and expected frequency. Then model tables and indexes around them. If you have a “dashboard” endpoint that hits five tables, expect it to be the first thing that falls over under load.

In products like L.E.D.A., where analytics workflows matter, we often separate operational data from derived views. Operational tables stay normalized enough to keep writes correct. Derived tables or materialized views serve fast reads. This reduces query complexity and gives you control over freshness.

- Operational store: correct writes, strict constraints, transactional updates.

- Read models: precomputed aggregates, denormalized projections, cached slices.

- Event log: optional, but useful when you need replay and audit.

Use migrations as a first class workflow

Migrations need to be boring. That means: small changes, backwards compatible steps, and automation in CI. For PostgreSQL, avoid long locks on hot tables. Add columns as nullable, backfill in batches, then enforce constraints later. This takes more steps, but it prevents long outages.

Tools depend on the stack. Prisma Migrate, TypeORM migrations, Flyway, Liquibase, and Rails migrations can all work. What matters is discipline: every change is versioned, reviewed, and applied the same way in every environment.

If a migration can lock a table for 30 seconds in production, assume it will happen at the worst possible time.

Partition and archive before you need it

Large tables grow quietly until a query plan flips and latency spikes. If you have append heavy tables (events, logs, transactions), consider partitioning by time or tenant. PostgreSQL native partitioning works well when you keep partition counts sane and queries align with the partition key.

Also plan for retention. Many SaaS products do not need infinite history in the hot path. Archive old records to cheaper storage or a separate database. The best time to add retention is before customers treat “forever” as a promise.

Backend architecture: modular monolith first, services when forced

Microservices can scale teams, but they also scale coordination costs. For many SaaS products, a modular monolith is the fastest route to stability. You keep one deployment unit, one database, and one set of operational dashboards. You still enforce module boundaries in code.

We often start with a modular monolith and extract services only when there is a clear pressure: different scaling needs, different release cadence, or a high risk boundary like payments. This is not a purity test. It is cost control.

Define modules with hard edges

Hard edges mean no cross module database writes and no “just import that function.” Use explicit interfaces. Keep modules in separate folders with strict lint rules. If the language supports it, enforce boundaries with tooling.

In TypeScript, you can enforce boundaries with path aliases plus ESLint rules, or use a tool like dependency-cruiser. In JVM stacks, use package conventions and architectural tests. The point is to catch coupling early, before it becomes a refactor that never fits into a sprint.

- Identity: auth, sessions, roles, tenant membership.

- Billing: plans, invoices, usage, entitlements.

- Core domain: the product’s main objects and workflows.

- Integrations: external APIs, webhooks, connectors.

Async work: queues, idempotency, and retries

Background jobs are where “it worked locally” goes to die. You need idempotency, retry policies, and dead letter handling. A queue without those is just a faster way to create duplicates and partial state.

Common tools include SQS, RabbitMQ, BullMQ (Redis), and managed Kafka. Pick based on your needs. If you need strict ordering and replay, Kafka helps but adds ops complexity. If you need simple fan out and retries, SQS is often enough.

type Job = {

idempotencyKey: string;tenantId: string;type: "SEND_EMAIL";payload: {

to: string;template: string;vars: Record

};

};

async function handleJob(job: Job, db: any, email:

any) { // Idempotency table: (tenantId, idempotencyKey) unique const exists = await db.processedJob.findUnique({ where: { tenantId_idempotencyKey: { tenantId: job.tenantId, idempotencyKey: job.idempotencyKey } } }); if (exists) return; await email.send(job.payload); await db.processedJob.create({ data: { tenantId: job.tenantId, idempotencyKey: job.idempotencyKey, processedAt: new Date() } });

}This pattern costs an extra write, but it saves you from duplicate emails when retries happen. The same idea applies to webhooks, invoice creation, and any workflow that can be triggered twice.

Observability and operations: measure what breaks first

Scaling without observability is guessing under stress. Logs alone are not enough. You need metrics, traces, and clear ownership of alerts. Otherwise you will learn about outages from customer messages, and the postmortem will end with “add more logging.”

We aim for a setup where a developer can answer three questions in minutes: what changed, what is failing, and who is affected. That requires consistent correlation IDs, structured logs, and dashboards tied to SLOs.

Metrics, logs, traces: pick a baseline stack

OpenTelemetry is a practical standard for instrumenting services. It works across languages and vendors. You can send telemetry to tools like Datadog, Grafana stack (Prometheus, Loki, Tempo), New Relic, or others. The vendor matters less than consistency.

Start with a small set of golden signals per service: latency, traffic, errors, saturation. Add domain metrics next: jobs processed, payment failures, webhook retries, and cache hit rates. Domain metrics are often the first signal of a customer facing issue.

- Request tracing: one trace per request, with DB spans and external API spans.

- Structured logs: JSON logs with tenantId, userId, requestId.

- Dashboards: one per user journey, not one per component.

Alerting that does not train people to ignore it

Bad alerts are worse than no alerts. They teach the team to mute notifications. Alert on symptoms tied to SLOs, not on every spike. If CPU hits 80% for two minutes but latency is fine, that is not a page. If p99 latency breaches for ten minutes, it probably is.

Also route alerts to the right owner. A billing failure alert should wake the person who can fix billing, not the whole team. Keep an on call runbook short. Include the first three checks and the rollback path.

- Alert on SLO burn rate and error rate, not raw resource thresholds.

- Include tenant impact when possible (top affected tenants by errors).

- Require a runbook link or inline steps for every page-level alert.

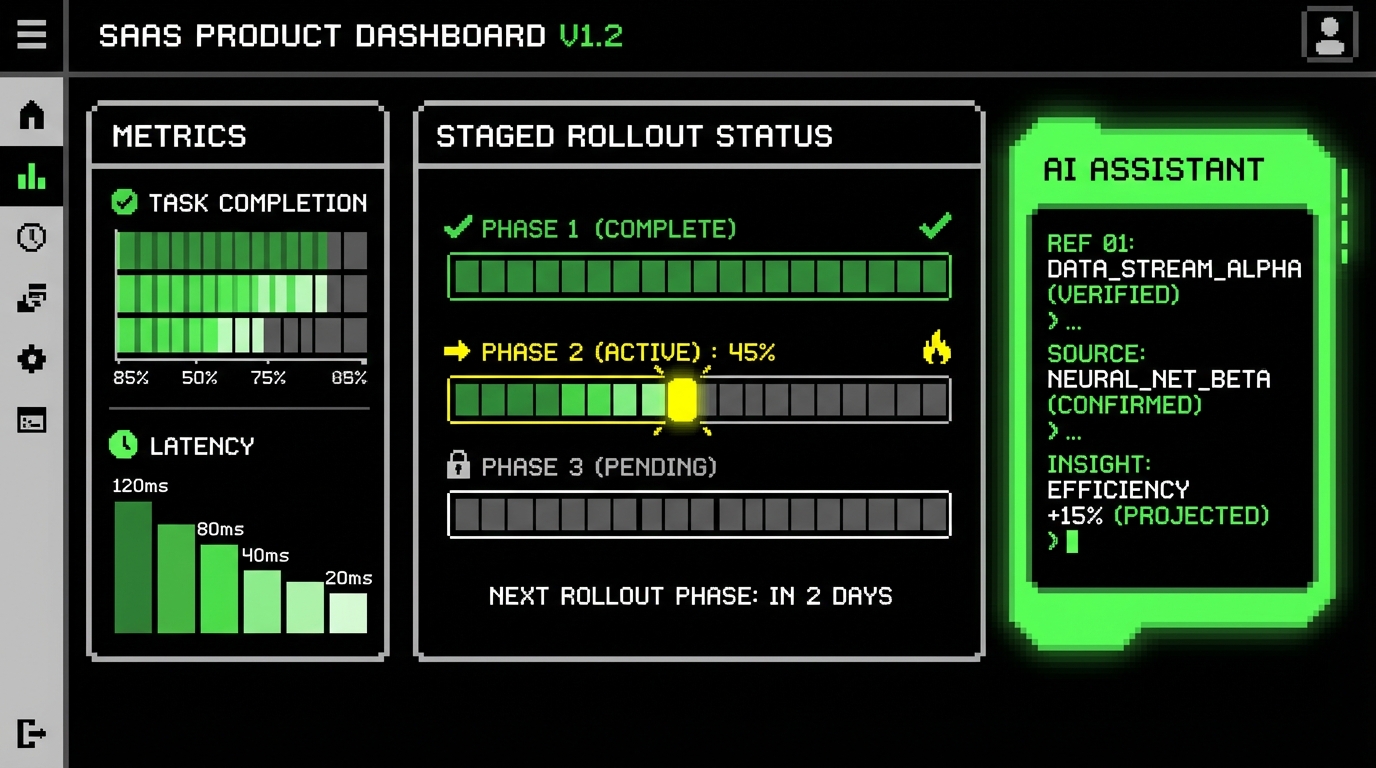

Delivery pipeline: CI/CD, environments, and safe releases

Flexible SaaS needs repeatable delivery. If deployments are manual, they will be delayed. Delayed deployments lead to large batches. Large batches make rollbacks scary. This loop is common, and it blocks growth.

We standardize on a few practices: automated tests at the right layers, preview environments for review, and release controls like feature flags. On projects with tight timelines, a solid pipeline saves more time than any code generator.

CI that catches the expensive failures early

Not all tests are equal. Unit tests catch logic errors fast. Integration tests catch broken contracts with databases and queues. End to end tests catch user journey regressions but are slow and flaky if overused. A balanced suite keeps CI under 10 to 15 minutes for most commits.

In SaaS builds we often add contract tests for external APIs and webhook payloads. External integrations fail in production in ways mocks never show. A nightly job that hits a sandbox API can catch breaking changes before customers do.

- Lint + typecheck: fast feedback, blocks obvious mistakes.

- Unit tests: core logic, pure functions, edge cases.

- Integration tests: DB migrations, queues, auth flows.

- Smoke tests: post-deploy checks on key endpoints.

Release safety: feature flags and progressive delivery

Feature flags let you ship code without exposing it to everyone. They also let you do tenant based rollouts, which is useful when one tenant has a custom workflow or large data volume. Tools include LaunchDarkly, Unleash, or a simple in-house flag service if needs are modest.

Progressive delivery is not only for huge scale. Even a small SaaS benefits from canary releases: deploy to a small slice, watch metrics, then ramp up. If your platform supports it, use blue green or rolling deployments with health checks.

type Flags = {

newBillingFlow: boolean

};

function isEnabled(flags: Flags, tenantId: string):

boolean { // Example: enable for internal tenants and a small allowlist const allowlist = new Set(["tenant_internal", "tenant_beta_1"]); return flags.newBillingFlow && allowlist.has(tenantId);

}

async function createInvoice(input: any, flags: Flags, tenantId: string) {

if (isEnabled(flags, tenantId)) {

return createInvoiceV2(input);

}

return createInvoiceV1(input);

}Flags can become a mess if you never remove them. Set an expiry date. Track flags like debt. Delete them once the rollout is done.

Security, compliance, and cost controls that scale with you

Security work that starts late is usually reactive. You add controls after an incident or a customer questionnaire. That costs more and it tends to create awkward patches. It is better to bake in baseline controls early, even if the product is small.

Cost is also part of scaling. A system that handles 10x traffic but costs 20x is not healthy. Cost spikes often come from unbounded background jobs, chatty APIs, and overprovisioned databases.

Baseline security: the boring checklist that prevents big incidents

Most SaaS security wins come from basic hygiene: strong auth, least privilege, secret management, and audit logs. Add rate limiting on auth endpoints. Hash passwords with a modern algorithm. Store secrets in a managed vault, not in environment files shared over chat.

For products that handle transactions or sensitive retail data, auditability matters. You do not need a full SIEM to start. You do need immutable logs for key actions: role changes, payout actions, webhook configuration, API key creation.

- Auth: OAuth/OIDC where possible, MFA for admins, short-lived tokens.

- Authorization: explicit policies, tenant checks everywhere, deny by default.

- Secrets: managed secret store, rotation process, no secrets in build logs.

- Data: encryption at rest, TLS in transit, field-level encryption for high risk fields.

Cost controls: budgets, load tests, and “no unbounded loops”

Set cloud budgets and alerts early, even if the numbers are small. A runaway queue consumer or a log ingestion spike can surprise you. Many teams only add budgets after the first painful bill.

Load testing should target known bottlenecks, not random endpoints. Tools like k6, Gatling, Locust, and JMeter can all work. Start with a test that matches one user journey and run it on every major release. Track three numbers: throughput, p95 latency, and cost per 1,000 requests.

A flexible SaaS has a cost model you can explain in one sentence, like “each active tenant adds X jobs per day and Y MB of storage per month.”

Conclusion: scaling is a set of habits, not a rewrite

Flexible SaaS comes from repeated, concrete choices: enforce tenant boundaries, keep migrations safe, make async work idempotent, and measure the system with signals tied to SLOs. The tools matter, but the habits matter more. A good stack with weak discipline still fails under growth.

If you want one practical next step, write down your scaling brief and pick three numbers to track weekly: a latency SLO, an error budget burn rate, and a cost metric tied to usage. Then use those numbers to guide architecture changes. This keeps scaling work grounded in what users feel and what the business pays.

When we deliver SaaS at Apptension, we try to keep the first version simple while leaving room for the hard requirements that show up later. That usually means a modular monolith, strict tenant context, predictable pipelines, and observability from day one. It is not glamorous work, but it prevents the kind of growth that breaks trust.