QA used to mean one main thing: given the same input, the system should behave the same way. AI features break that assumption. A prompt tweak, a model version update, or a changed retrieval index can shift outputs without any code change. That is not a rare edge case. It is normal.

In delivery work at Apptension, we see teams ship AI features fast, then struggle to explain regressions. The bug report often sounds like “it got worse,” not “step 3 throws a 500.” QA still matters, but the unit of work changes. You test behavior, risk, and cost, not only correctness.

This article focuses on practical QA for AI powered systems, especially LLM features. It covers what to measure, what to automate, and what to treat as a product decision. It also calls out what fails in real projects, so you can avoid building a test suite that looks serious but catches nothing.

What changes when software includes AI

AI adds a probabilistic component to a pipeline that used to be deterministic. Even if your code is stable, the model output can vary across runs due to sampling, backend updates, or subtle context differences. That means classic assertions like “response equals X” often turn into “response should satisfy constraints.” Those constraints must be explicit, or QA becomes opinion.

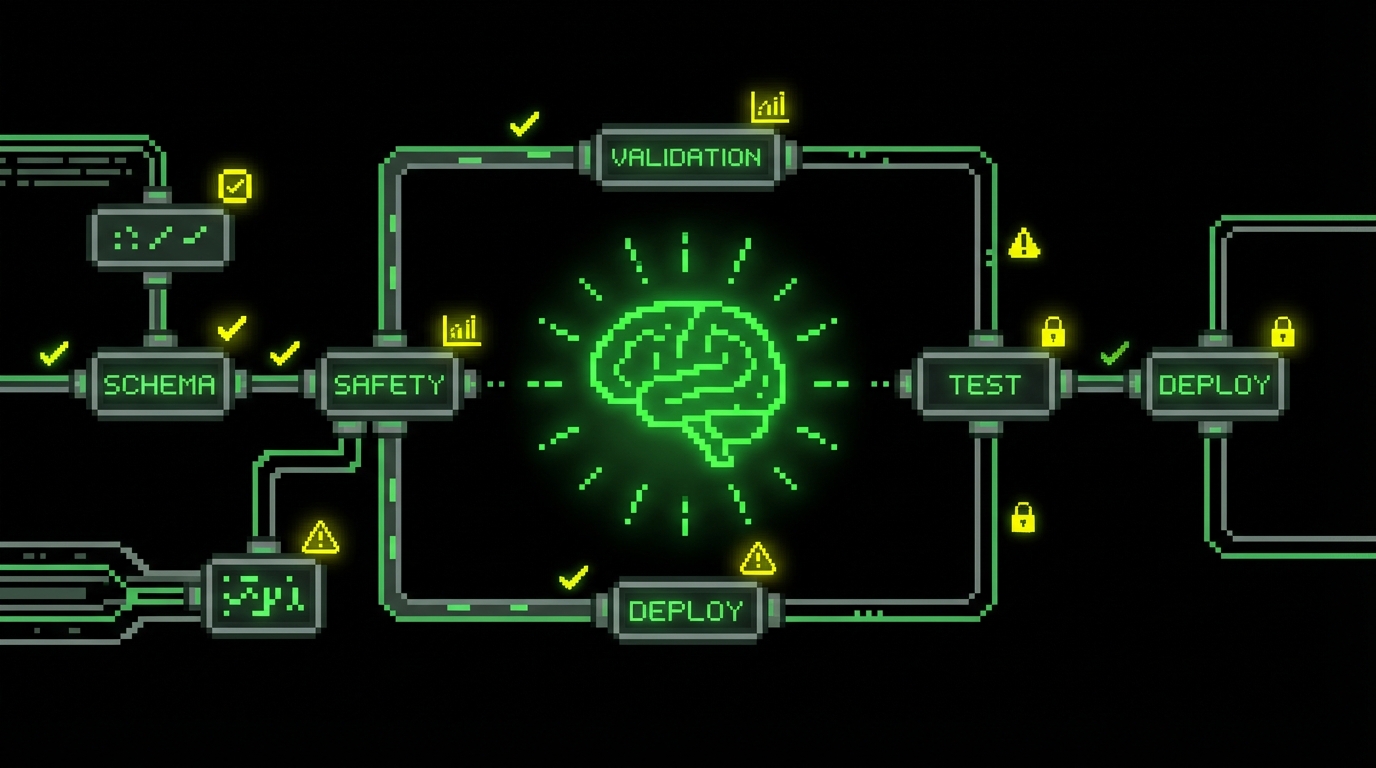

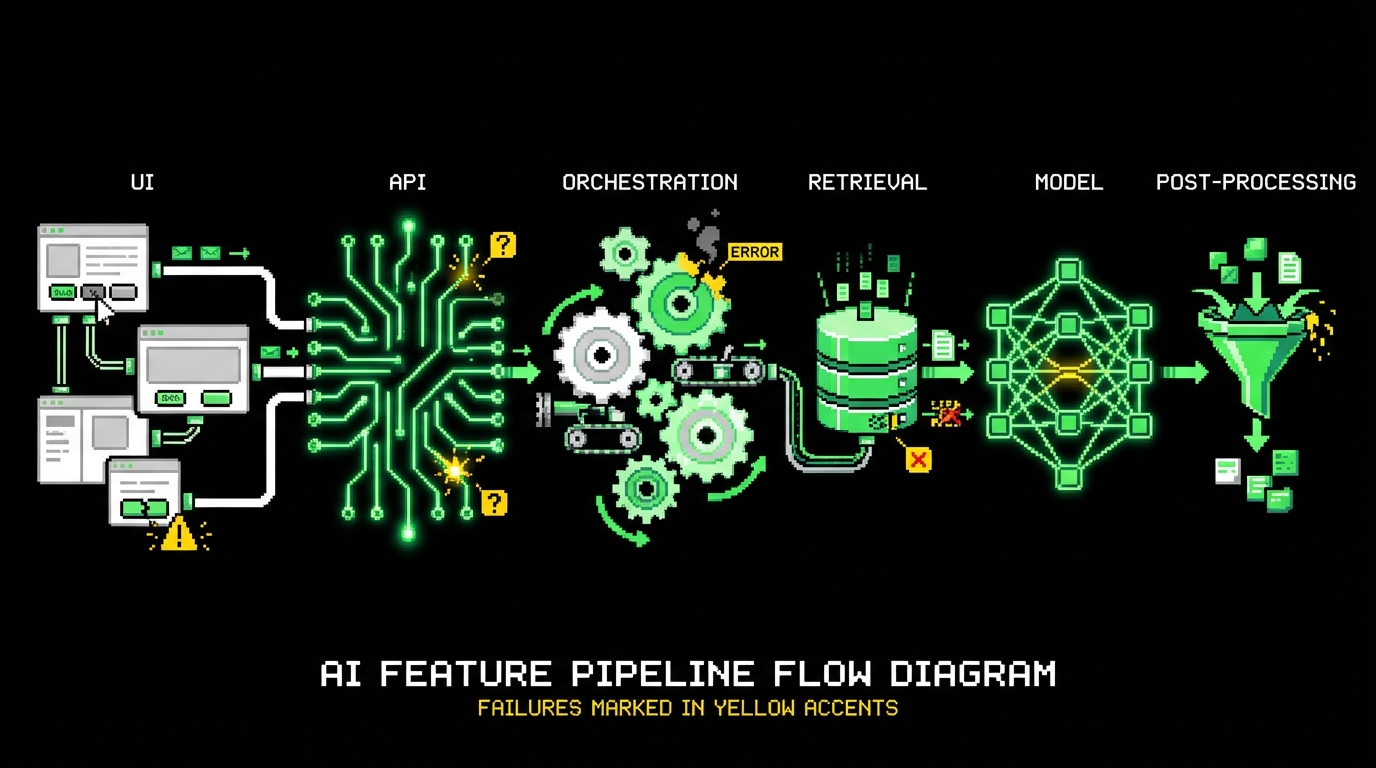

AI also expands the surface area of “inputs.” A user prompt is an input, but so is hidden system context, retrieved documents, tool outputs, and conversation history. Bugs can come from any of these layers. In practice, you debug a chain: UI → API → orchestration → retrieval → model → post processing. QA needs visibility across the chain, not only end to end screenshots.

Finally, AI features introduce new failure modes that are not typical for CRUD apps. You get hallucinations, prompt injection, data leakage, and silent cost spikes. These failures do not always show up as errors. A response can be fluent and wrong, or safe and useless, or correct but too expensive to run at scale.

Determinism is a choice, not a default

Teams often expect the model to behave like a library function. It will not, unless you force it to. You can lower temperature, fix seeds where supported, pin model versions, and freeze retrieval indexes. Each of these choices has a cost. Lower temperature can reduce creativity. Pinning models can block improvements. Freezing an index can make answers outdated.

QA should not demand full determinism everywhere. Instead, pick which parts must be stable. For example, a compliance summary for a legal workflow needs narrow variance. A brainstorming assistant can tolerate more variety. The key is to declare the tolerance and test against it.

“Correctness” becomes multi-dimensional

For many AI tasks there is no single correct answer. A support reply can be acceptable if it is polite, consistent with policy, and grounded in the right source. That means QA needs multiple checks. Some are objective, like “no PII in output.” Some are semi objective, like “includes a citation.” Some are subjective, like “tone matches brand voice.”

This is where teams get stuck. They try to turn everything into a binary pass or fail. The better approach is to combine hard gates (must pass) with scored evaluation (should improve). You still ship with confidence, but you stop pretending that all quality is boolean.

Define quality for AI features: what you actually test

Before you write a single test, you need a quality spec. Not a vague statement like “answers should be good,” but a set of measurable constraints. In Apptension projects, we treat this as part of discovery for AI features. If a team cannot describe what “good” means, automation will not save them.

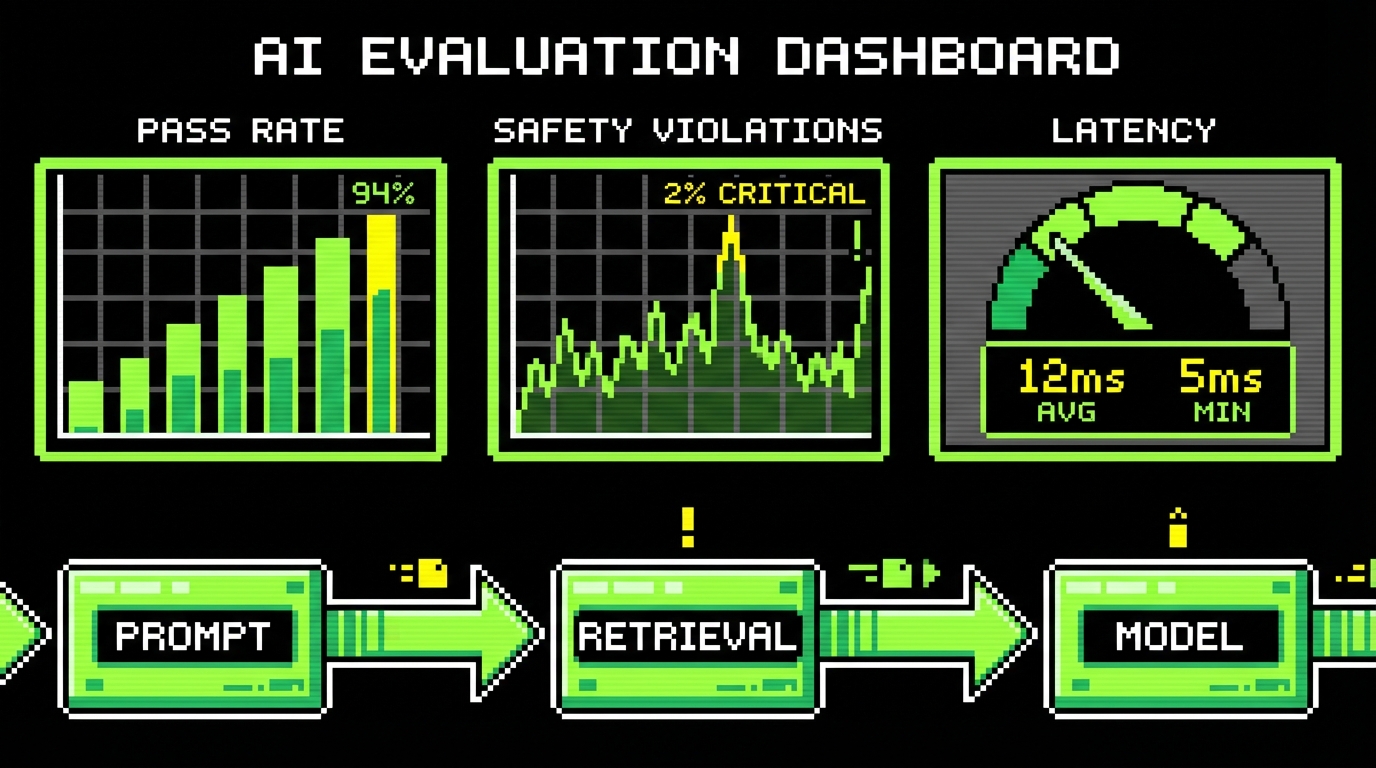

A useful spec separates three categories: functional behavior, risk controls, and operational limits. Functional behavior covers task success. Risk controls cover safety, privacy, and policy. Operational limits cover latency and cost. The last one is often forgotten until the first invoice arrives.

Here is a concrete checklist that works across many LLM use cases:

- Task success: does the output contain required fields, follow format, and answer the question?

- Grounding: does it cite sources, and do claims match retrieved content?

- Safety: does it refuse disallowed requests and avoid harmful advice?

- Privacy: does it avoid exposing secrets, tokens, or user data?

- Robustness: does it handle empty context, long inputs, and adversarial prompts?

- Latency: p95 response time under expected load.

- Cost: tokens per request, tool calls, retrieval calls, and their ceilings.

Golden datasets: your most valuable QA asset

A golden dataset is a curated set of prompts and contexts that represent real usage. It includes edge cases, known tricky questions, and policy traps. It also includes the expected constraints, not necessarily an exact expected answer. Without this dataset, regression testing becomes guesswork.

We build golden datasets from three sources: production logs (with privacy controls), stakeholder examples, and synthetic generation. Production logs give realism. Stakeholder examples capture business critical flows. Synthetic generation helps fill gaps, but it can also create a false sense of coverage if you only generate “clean” prompts.

Keep the dataset versioned. Treat changes as code changes. When stakeholders add a new requirement like “always include a disclaimer,” add cases that enforce it. Over time, your dataset becomes the shared language between QA, product, and engineering.

Hard gates vs scored evaluation

Hard gates are checks that must always pass. Examples include “no secrets in output,” “JSON parses,” and “does not mention internal system prompt.” Scored evaluation is for quality that improves gradually, like helpfulness or tone. Mixing the two leads to brittle tests and constant false alarms.

A practical pattern is to run hard gates on every pull request and every deployment. Run scored evaluation on a schedule or on release candidates. That keeps CI fast while still tracking quality trends. It also gives product teams room to iterate without blocking on subjective debates.

Test pyramid for AI: where automation works and where it lies

End to end tests alone are not enough. They tell you something is wrong, but not where. For AI systems, you need layered tests that isolate failures in prompting, retrieval, tools, and post processing. Otherwise each regression becomes a long debugging session with screen recordings and opinions.

We still use the idea of a test pyramid, but the layers look different. At the base you test deterministic code: parsers, validators, routing logic, and permission checks. In the middle you test orchestrations with mocks: retrieval returns fixed documents, tools return fixed outputs, and the model is stubbed. At the top you run a smaller set of live model evaluations against the golden dataset.

Here is a simple map of test types that tends to work:

- Unit tests: prompt builders, output schemas, redaction, policy rules.

- Contract tests: tool interfaces, retrieval API shape, model client retries and timeouts.

- Scenario tests with stubs: full orchestration with deterministic fixtures.

- Live evals: a limited set of cases against the real model and index.

Make outputs machine-checkable

If your AI feature returns free text only, automation will be weak. You can still test for banned phrases, length, or required sections, but you will miss many failures. A better approach is to force structure where it matters. Use JSON schemas, typed fields, and explicit citations.

In one Apptension delivery, we moved a “summary” feature from plain text to a structured response with fields like summary, risks, and sourceIds. That did not make the model perfect. It made QA possible. The tests could validate schema and verify that each claim referenced a source.

Don’t overfit to the model today

A common trap is writing tests that encode the quirks of one model version. They pass today and fail after a model patch, even if the feature is still acceptable. This happens when you check exact phrasing, or when your “expected answer” is too narrow.

Prefer assertions on constraints: format, required facts, disallowed content, and citation presence. When you need to check facts, ground them in retrieval content. When you need to check style, use a small set of stable style rules rather than full text matching.

Automating AI checks: pragmatic techniques and examples

Automation for AI QA is not magic. It is a set of small checks that reduce risk. Some checks are deterministic. Others use a second model as a judge. Both approaches can work. Both can fail if you do not measure false positives and false negatives.

We usually start with deterministic checks because they are cheap and predictable. Then we add model-based evaluation for things that humans care about but code cannot easily verify, like “did it answer the question” or “is the refusal correct.” When using a judge model, we keep the rubric short and we log the judge’s reasoning for audits.

Below are three code examples that show common building blocks: schema validation, groundedness checks, and a simple eval runner. They are not a full framework, but they are the parts you can drop into an existing codebase.

Schema validation as a hard gate (TypeScript)

Force the model to output JSON and validate it. This catches a large class of failures: partial outputs, missing fields, and format drift after prompt edits. It also makes downstream code safer because you stop treating model output as trusted text.

The example uses a schema to validate a response object. If validation fails, you can retry with a repair prompt, or fail fast and return a safe fallback.

import {

z

} from "zod";

const AnswerSchema = z.object({

answer: z.string().min(1),

citations: z.array(z.object({

id: z.string(),

quote: z.string().min(1)

})),

safety: z.object({

containsPII: z.boolean(),

refusal: z.boolean()

})

});

type Answer = z.infer;

export function parseModelOutput(raw: string): Answer {

const json = JSON.parse(raw);

return AnswerSchema.parse(json);

}Groundedness check against retrieved chunks (Python)

If you use retrieval augmented generation, you can test whether the answer is supported by the retrieved text. This will not prove truth, but it can catch obvious hallucinations. A simple version checks that each citation quote exists in the retrieved chunks.

This is a hard gate when you require citations. It is also useful as a metric: percentage of answers with valid citations over time.

from typing import List, Dict def citations_exist(citations: List[Dict], retrieved_chunks: List[str]) -> bool: haystack = "\n".join(retrieved_chunks) for c in citations: quote = (c.get("quote") or "").strip() if len(quote) < 10: return False if quote not in haystack: return False return TrueA tiny eval runner with thresholds (Python)

For scored evaluation, you need repeatable runs. The runner below executes cases from a golden dataset and records pass rates for hard gates plus a simple score. In real systems, the score may come from a judge model or a rubric based on heuristics.

The important part is the threshold. You decide what is acceptable and fail the build only when you cross that line. That prevents constant noise while still catching quality drops.

def run_evals(cases, predict_fn, score_fn, min_pass_rate = 0.95, min_avg_score = 0.75): passed = 0 scores = [] for case in cases: out = predict_fn(case) if out["hard_gates_ok"]: passed + = 1 scores.append(score_fn(case, out)) pass_rate = passed / max(len(cases), 1) avg_score = sum(scores) / max(len(scores), 1) if pass_rate < min_pass_rate or avg_score < min_avg_score: raise AssertionError( {

"pass_rate": pass_rate, "avg_score": avg_score

}) return {

"pass_rate": pass_rate, "avg_score": avg_score

}Security, privacy, and prompt injection: QA as defense

AI features often sit on top of sensitive data: internal docs, customer tickets, account details, or code. That makes QA part of security. You are not only checking “does it work.” You are checking “can it be tricked into leaking.” This is where traditional QA and AppSec overlap.

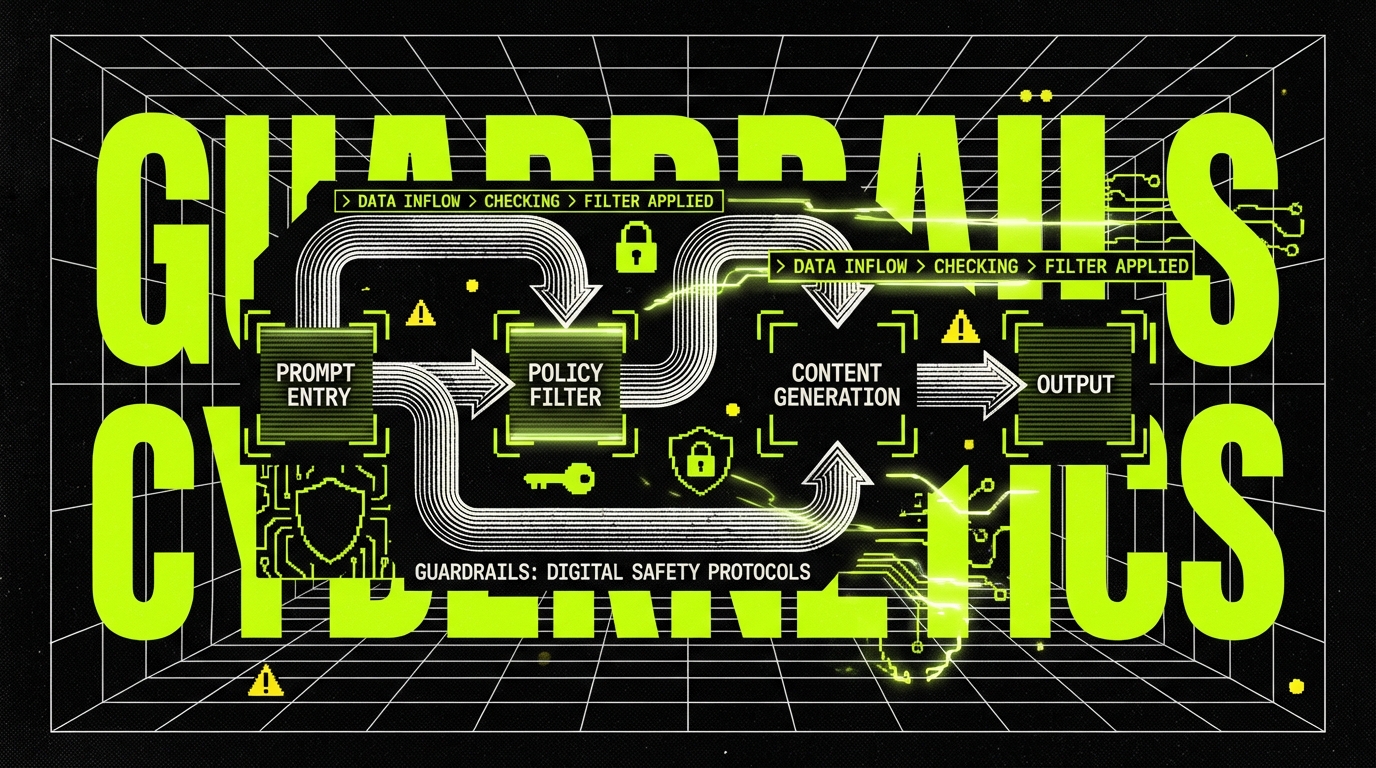

Prompt injection is a common example. A user can paste instructions that try to override system rules, extract hidden prompts, or request data outside their permissions. If your system uses tools, the risk grows. The model might call a tool with unsafe parameters unless you enforce guardrails in code.

In practice, we treat these as test cases in the golden dataset, tagged as security. We also add deterministic controls that do not depend on the model behaving well. The model should be the last line of defense, not the first.

What to test for prompt injection

Injection tests should cover both direct and indirect attacks. Direct attacks are in the user prompt. Indirect attacks hide in retrieved documents, like a malicious sentence inside a PDF that says “ignore previous instructions.” If you do RAG, you need both.

Concrete test cases that catch real problems:

- Requests to reveal system prompts or hidden instructions.

- Requests to output API keys, tokens, or environment variables.

- Instructions to call tools with escalated scope (for example, “export all users”).

- Malicious content in retrieved docs that attempts to override tool usage rules.

Deterministic guardrails that reduce QA burden

Some controls should never be delegated to a model. Permission checks belong in your backend. Tool allowlists belong in your orchestration layer. Output redaction should run after the model responds, even if you also ask the model to avoid PII.

When these controls exist, QA becomes simpler. You can test them like normal code. You still test the model’s behavior, but you stop relying on it for basic safety guarantees.

Rule of thumb: if a failure would become a security incident, do not rely on the model to prevent it.

Observability and drift: QA after release

For AI features, shipping is not the end of QA. Quality can drift even if your code does not change. The retrieval corpus changes. User behavior changes. Model providers roll out updates. If you do not measure quality in production, you will learn about regressions from angry users.

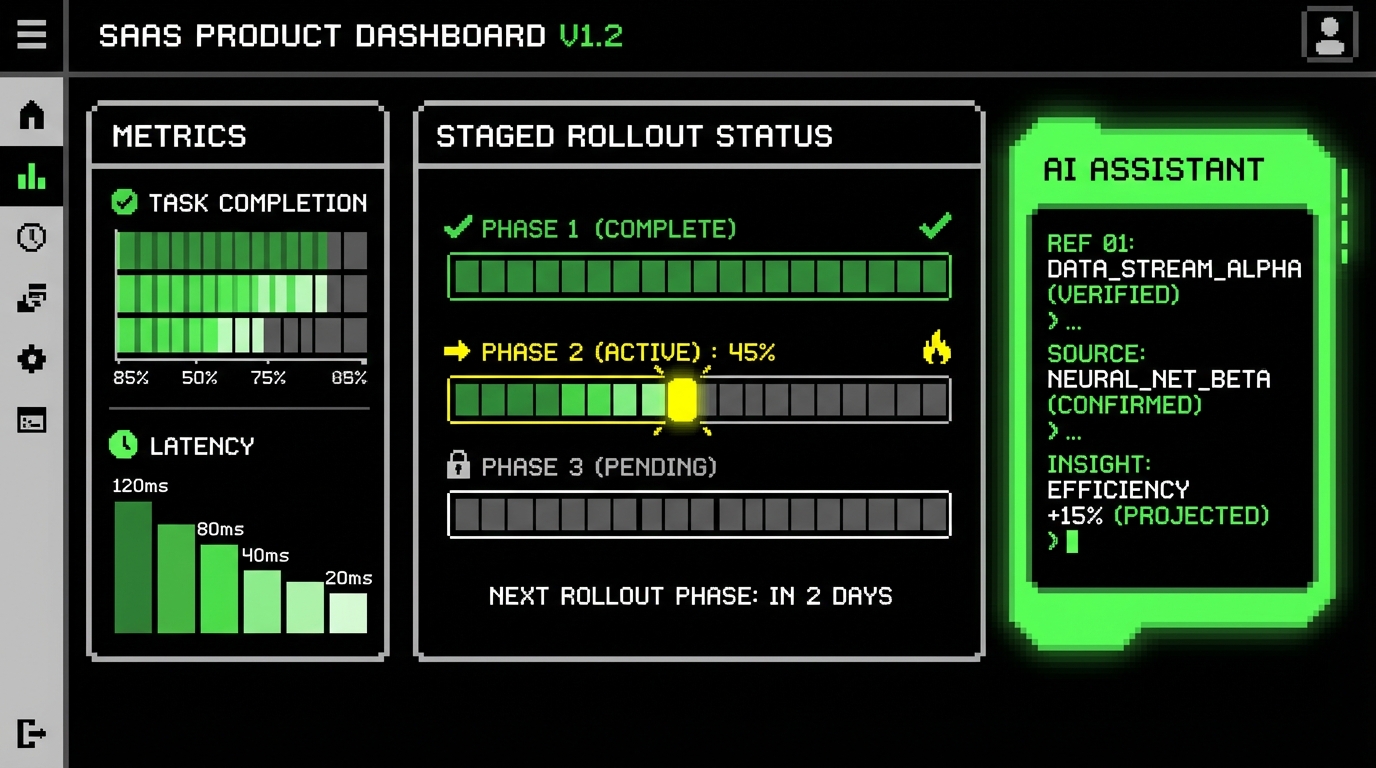

We set up observability with three layers: traces for each step of the pipeline, metrics for latency and cost, and sampled logs for quality review. Traces help debugging. Metrics catch cost spikes. Sampled logs help humans see what users see. All three matter.

Useful metrics for AI QA tend to be simple and practical:

- Token usage: average and p95 tokens in and out per request.

- Latency: p50 and p95 end to end, plus per step (retrieval, model, tools).

- Refusal rate: percentage of requests refused, split by reason.

- Citation validity rate: percentage of outputs with citations that match retrieved text.

- Fallback rate: how often you hit safe defaults due to parsing or policy failures.

Drift detection with scheduled evals

Scheduled evals are the simplest drift detector. Run the golden dataset daily or weekly against the production configuration. Compare pass rates and scores to a baseline. Alert on meaningful drops, not tiny noise.

In one project, we saw a drop in citation validity after a content ingestion change. The model did not change. The chunking strategy did. Without scheduled evals, the team would have blamed the model and wasted days. With evals, they traced the regression to chunk boundaries and fixed it in a few hours.

Human review still matters, but make it cheap

Some issues only show up to humans: subtle tone problems, missing empathy, or answers that are technically correct but confusing. You can still manage this with process. Sample a small percentage of conversations, redact sensitive fields, and review them with a short rubric.

Keep the rubric tight. Five questions is enough. Track agreement between reviewers. If two people disagree most of the time, your rubric is not clear enough to support QA decisions.

How QA teams work with AI: roles, rituals, and pitfalls

AI QA sits between product, engineering, data, and security. That can get messy fast. The cleanest approach is to assign ownership of the quality spec and the golden dataset. In our teams, QA often owns the dataset curation and hard gate definitions, while engineering owns guardrails and instrumentation. Product owns acceptance thresholds.

Rituals matter because AI behavior changes with small edits. A prompt change should have a review process, just like code. We treat prompts as versioned artifacts. We run evals before merging. We keep a changelog for prompt and retrieval changes, so regressions have a timeline.

Common pitfalls show up across teams:

- Testing only happy paths: the demo works, production fails on messy inputs.

- No cost budget: quality improves but token usage doubles quietly.

- Overtrusting judge models: the judge agrees with fluent nonsense.

- Skipping fixtures: no deterministic stubs, so every test run is noisy.

- No incident playbook: when quality drops, nobody knows what to roll back.

What works in delivery settings

In client work, timelines are real and tradeoffs are visible. The practices that survive are the ones that fit into CI and sprint cycles. A small golden dataset is better than a perfect one that never ships. A few strong hard gates reduce risk more than a complex scoring system that nobody trusts.

We also see value in pairing QA with an engineer for the first eval harness. Once the harness exists, QA can extend datasets and rubrics without deep changes to the code. That keeps iteration fast and reduces the “AI testing is only for specialists” problem.

When not to automate

Some checks are not worth automating early. For example, brand voice can be important, but it is hard to score reliably. If you automate it too soon, you will spend time arguing with the test suite. Start with a human review sample and add automation only when you have stable rules.

Another example is open ended creativity. If the feature is meant to generate many valid outputs, strict scoring can push it toward bland responses. In that case, QA should focus on safety, format, and obvious failure modes, not on ranking outputs.

Conclusion: QA stays, but the target moves

QA in the AI era is still QA. You define expected behavior, you control risk, and you prevent regressions. The difference is that you do it with constraints and metrics, not only exact outputs. You also accept that some quality work continues after release, because drift is normal.

The teams that ship stable AI features do a few simple things well: they build a golden dataset, they enforce hard gates, they add deterministic guardrails, and they measure cost and latency. They also keep humans in the loop where automation is weak. None of this is glamorous, but it works.

If you are adding AI to an existing product, start small. Pick one workflow, define its quality spec, and build the eval harness around it. Once you can detect regressions and explain failures, scaling to more features becomes a normal engineering problem, not a guessing game.