AI coding discussions often split teams into two groups. One group sees faster scaffolding, fewer boring tasks, and quick prototypes. The other group sees hallucinated code, security risks, and a slow drift toward unmaintainable systems.

Both groups are reacting to real outcomes. We have seen AI tools help engineers move faster on well scoped tasks, especially around boilerplate, tests, and documentation. We have also seen them produce confident nonsense, copy patterns that do not fit the codebase, and hide subtle bugs in “working” code.

This article is about bridging that gap with practical engineering habits. Not a tool comparison and not a pep talk. We will look at what AI is good at, what it is bad at, and how to make it a predictable part of delivery at Apptension style quality bars.

Why the debate gets stuck: different definitions of “works”

Enthusiasts often judge success by time to first working version. If a feature demo runs in a staging environment, it “works.” Skeptics judge success by time to production and time to change. If the code is hard to reason about, hard to test, or risky to deploy, it does not “work” even if it compiles.

Those are both valid definitions, but they measure different things. AI assistants tend to optimize for local correctness and plausible structure, not for fit with your architecture. That mismatch creates the common pattern: fast first draft, slow integration, and even slower maintenance.

When we run delivery projects, the real unit of value is not “generated code.” It is shipped behavior with a supportable lifecycle. That means we need shared success criteria before we argue about tools.

Two questions that settle most arguments

When a team gets stuck in a loop of opinions, we ask two questions. First: what part of the lifecycle are we optimizing for, and how will we measure it? Second: what risks are acceptable for this product, given its users, data, and uptime needs?

Those answers often differ by product area. A marketing landing page and a payments flow do not share the same risk tolerance. Once the team names the constraints, AI coding becomes an engineering choice, not a belief system.

What AI coding is actually good at (and why)

AI assistants perform best when the task has a strong “shape.” That means common patterns, predictable inputs and outputs, and lots of examples in public code. In practice, this includes CRUD endpoints, form validation, simple migrations, test scaffolding, and refactors with clear before and after states.

The other sweet spot is translation work. Converting a JSON schema into TypeScript types, rewriting a function from one style to another, or drafting a first pass at documentation. These tasks reward fluency and consistency more than deep product context.

In Apptension projects, AI tends to help most in the first 30 to 60 minutes of a new slice of work. It can draft the skeleton, list edge cases, and propose tests. After that, the limiting factor is usually domain knowledge and integration details, not typing speed.

Tasks that tend to be net positive

When teams ask “where should we start,” we recommend starting with tasks that are easy to validate. If you can write a clear acceptance test or a tight contract, you can safely accept help on the implementation.

- Test generation: unit tests for pure functions, snapshot tests for stable UI components, and basic API contract tests.

- Boilerplate creation: route handlers, DTOs, request validation, and repetitive wiring.

- Refactor assistance: renaming, extracting functions, and converting callback style to async patterns.

- Documentation drafts: README updates, runbooks, and “how to reproduce” notes for bugs.

These areas also have a clear “stop condition.” Either the tests pass and the code matches the style guide, or it does not. That makes AI output easier to accept or reject without long debates.

Where AI coding fails in production codebases

AI fails most often when the task depends on hidden context. That includes business rules that live in product decisions, edge cases that appear only in real data, and architecture constraints that are specific to your system. The model may produce code that looks right but violates invariants you rely on.

It also struggles with long range consistency. It can generate a function that is correct in isolation but mismatched with the rest of your module boundaries. Over time this creates a codebase that “works” but feels uneven, with different patterns for the same problem.

Finally, AI output can be risky because it is persuasive. Engineers may lower their guard when the code reads cleanly. That is how subtle bugs slip through review, especially when the reviewer assumes the author already validated the logic.

Common failure modes we see during delivery

These issues show up across stacks, whether it is Node, Python, or mobile. They are not “AI problems” so much as “validation problems,” but AI increases their frequency because it increases output volume.

- Incorrect assumptions: wrong timezone handling, wrong rounding rules, or assuming uniqueness where none exists.

- Security blind spots: missing authorization checks, unsafe deserialization, or naive input validation.

- Performance traps: N+1 queries, unbounded loops over large datasets, or inefficient regex patterns.

- Dependency drift: suggesting APIs that do not exist in your version, or mixing patterns from different frameworks.

If you recognize these as “normal bugs,” that is the point. AI does not introduce new categories of bugs as much as it changes the distribution. You get more plausible code faster, which means you must tighten feedback loops.

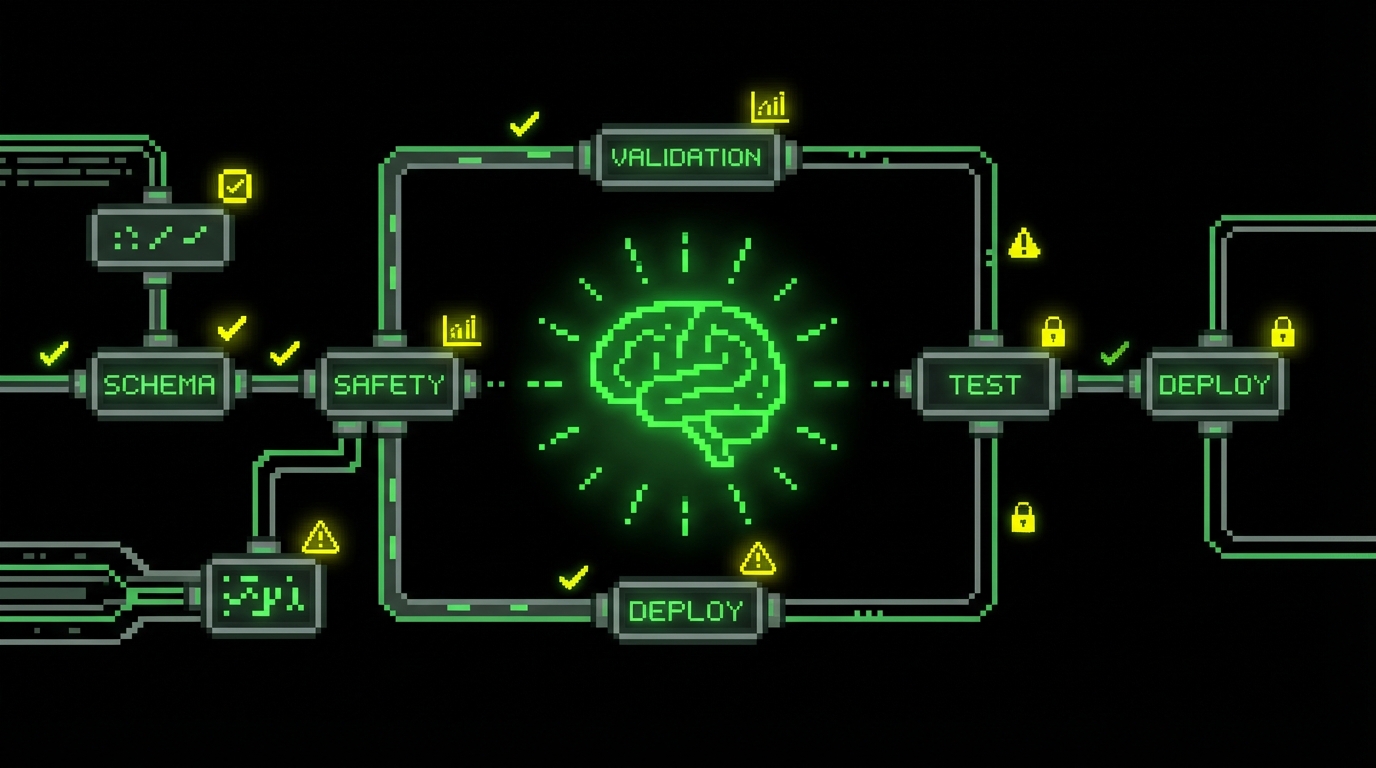

Guardrails that make AI output predictable

The goal is not to ban AI or to accept everything it produces. The goal is to make the output boring. Boring means consistent patterns, repeatable checks, and a clear path from draft to merged code.

We treat AI as a junior contributor that can type quickly. That framing helps. You would not merge a junior’s code without tests, review, and linting. You also would not ask them to redesign your domain model based on a vague prompt.

Guardrails work best when they are automated. If a rule is important but manual, it will be skipped on a Friday afternoon. If it is in CI, it becomes part of the product’s normal heartbeat.

A practical checklist for “AI assisted PRs”

This checklist is short on purpose. It fits into a PR template and does not require new meetings. Teams can adopt it in a day and iterate from there.

- State the contract: what inputs, outputs, and failure modes are expected.

- Add tests first or alongside: at least one failing test that the change makes pass.

- Run static checks: lint, typecheck, and security scanning in CI.

- Limit diff size: keep AI output in small PRs so review stays meaningful.

- Document assumptions: add comments only where business rules are encoded.

In practice, the “limit diff size” rule is the one that changes behavior most. AI can generate 300 lines in a minute, but review quality does not scale that way. Smaller PRs keep skeptics engaged because they can actually verify the code.

Three implementation patterns that work well

Teams often ask how to structure AI usage without turning it into a free for all. The simplest approach is to standardize a few patterns that match how you already build software. That way AI becomes a tool inside your workflow, not a parallel workflow.

Below are three patterns we have used in delivery contexts. They fit both greenfield and mature codebases. They also give skeptics the checks they need without blocking enthusiasts from drafting quickly.

Pattern 1: Contract first, generation second

Start with a contract that is hard to argue with. For an API, that can be a request schema and response shape. For a function, it can be types plus tests. Then ask AI to fill in the implementation that satisfies the contract.

This pattern works because it flips the dynamic. You are not asking “is this code good.” You are asking “does this code satisfy the contract and match our conventions.” That is a much easier review.

import {

z

} from "zod";

export const CreateUserInput = z.object({

email: z.string().email(),

name: z.string().min(1).max(120),

});

export type CreateUserInput = z.infer;This snippet is a simple example of a contract that AI can reliably build against. Once the schema is in place, you can generate handler code, validation middleware, and tests. Review then focuses on business rules, not on whether the email regex is correct.

Pattern 2: AI for refactors with mechanical verification

Refactors are a good fit when you can verify behavior mechanically. Snapshot tests, golden files, and type checks give you fast confidence. AI can propose the refactor steps, but the tests decide whether the change is acceptable.

We often use this for UI component cleanups in React or for reorganizing service layers in Node backends. The key is to keep the refactor separate from behavior changes. If you mix both, you lose the ability to validate quickly.

// Before: ad-hoc mapping

const labels = items.map((i) =>

`${i.id}:${i.name}`); // After: extracted and typed

type Item = {

id: string;name: string

};

export const toLabel = (i: Item) => `${i.id}:${i.name}`;

const labels2 = items.map(toLabel);This looks small, but it shows the idea. AI can do hundreds of these safely if your linter, type system, and tests run on every commit. Without those checks, refactors turn into “looks fine” reviews, which is where skeptics are right to worry.

Pattern 3: AI as a reviewer, not an author

Some teams get more value from AI in review mode than in writing mode. You write the code, then ask the model to look for edge cases, missing tests, and security concerns. This works well for skeptics because the source of truth remains the engineer’s intent.

It also helps when onboarding new team members. They can run a “second opinion” pass before requesting review. That reduces the back and forth on basic issues and keeps senior reviewers focused on architecture and product risk.

Measuring impact without fooling yourself

AI coding can feel fast while making delivery slower. The only way to know is to measure outcomes that matter. We prefer metrics that reflect the full lifecycle: build, review, deploy, and maintain.

At Apptension, we already track delivery signals on most projects: cycle time, PR size, review time, defect rate, and incident count. AI usage should show up in these numbers. If it does not, it is probably not helping, or it is helping only in ways that do not matter for the product.

Speed is not “lines per hour.” Speed is “time from decision to safe production.”

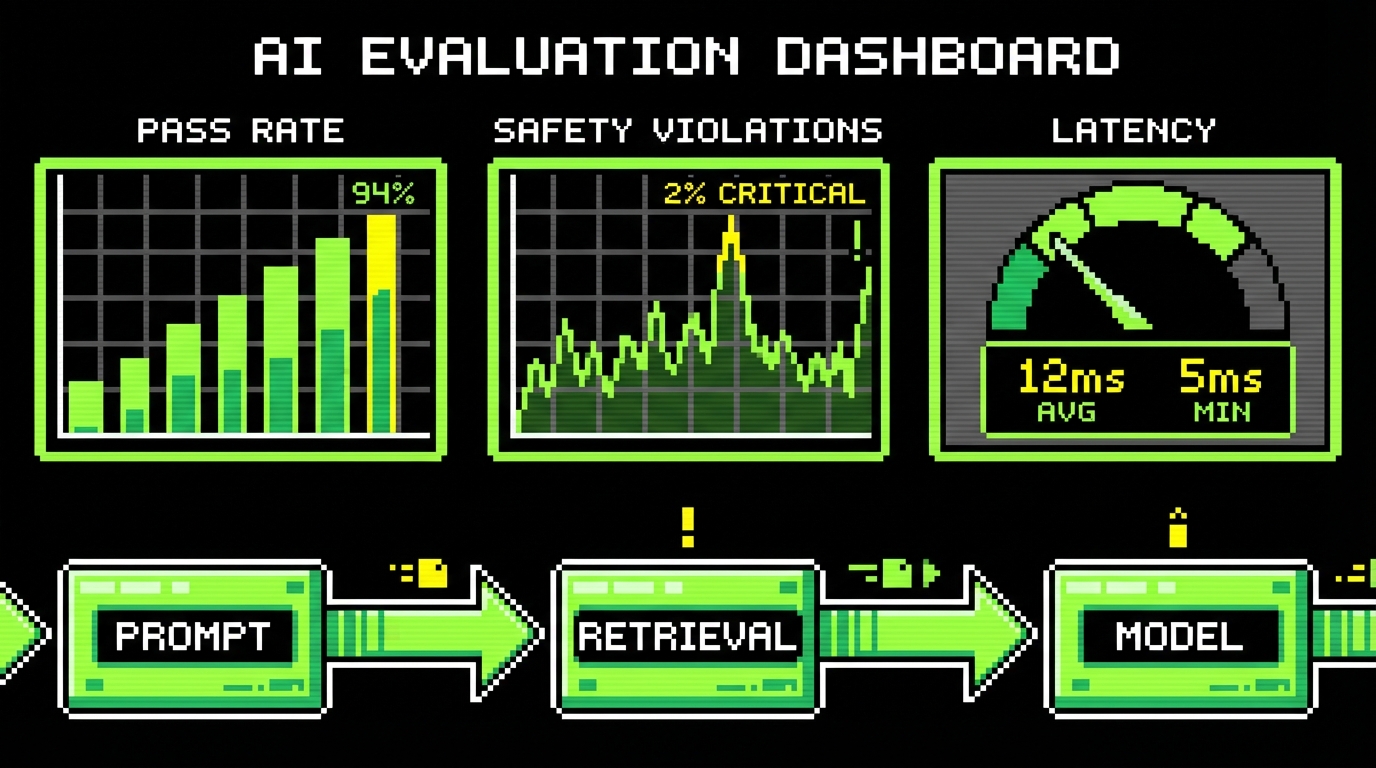

Metrics that correlate with real delivery health

You do not need a perfect measurement system. You need a small set of numbers that you can track for a few weeks before and after changing your workflow. Keep the scope tight so the team trusts the results.

- Cycle time: from first commit to merge, and from merge to deploy.

- PR size: median changed lines per PR, plus outliers.

- Review churn: number of review comments and number of follow up commits.

- Escaped defects: bugs found after release, grouped by severity.

- Build health: CI failure rate and time to green.

If AI is helping, you often see smaller PRs (because drafting is easier), faster first review, and stable escaped defect rates. If defect rates climb or review churn spikes, the team is paying the cost later.

How to bring skeptics along (without forcing adoption)

Skeptics are often the people who end up on call, or who maintain the most sensitive parts of the system. Their concerns are not “fear of change.” They are usually based on lived experience with production incidents and messy code.

The fastest way to build trust is to make AI usage observable and bounded. That means clear labeling in PRs, clear ownership of changes, and strict rules around security sensitive code. It also means agreeing up front on where AI is not allowed.

On teams where we saw adoption stick, the pattern was consistent: one or two enthusiasts proposed guardrails, skeptics helped tighten them, and then both sides used the same checks to decide what merges.

Rules of thumb that reduce friction

These rules are not about policing. They reduce surprises. Surprises are what turn a tool discussion into a trust discussion.

- Declare AI assistance in the PR description when it materially shaped the code.

- Do not use AI for secrets or proprietary data unless your setup and policies explicitly allow it.

- Keep AI out of the critical path first (auth, payments, encryption) until the team has baseline confidence.

- Prefer AI on code with strong tests and clear contracts.

- Rotate reviewers so knowledge does not concentrate in one “AI person.”

One practical note from product work: prototypes are a safe place to experiment. For example, in short discovery efforts like BeeLinked, speed matters because you are validating ideas quickly. In those contexts, AI can help draft UI states and copy quickly, while the team still keeps engineering discipline around what becomes production code later.

Conclusion: treat AI as output you must verify

AI coding is neither magic nor poison. It is a fast draft generator that can reduce friction on well defined work. It can also increase risk when teams accept output without tightening validation.

The divide between enthusiasts and skeptics closes when the team agrees on success metrics and builds guardrails into the workflow. Contracts, tests, small PRs, and CI checks do most of the work. Once those are in place, AI becomes less controversial because it becomes less dramatic.

If you want a simple next step, pick one area with strong tests and clear contracts. Run a two week experiment with a short checklist and track cycle time and escaped defects. Keep what improves delivery, drop what does not, and document the rules so new engineers inherit a stable system.