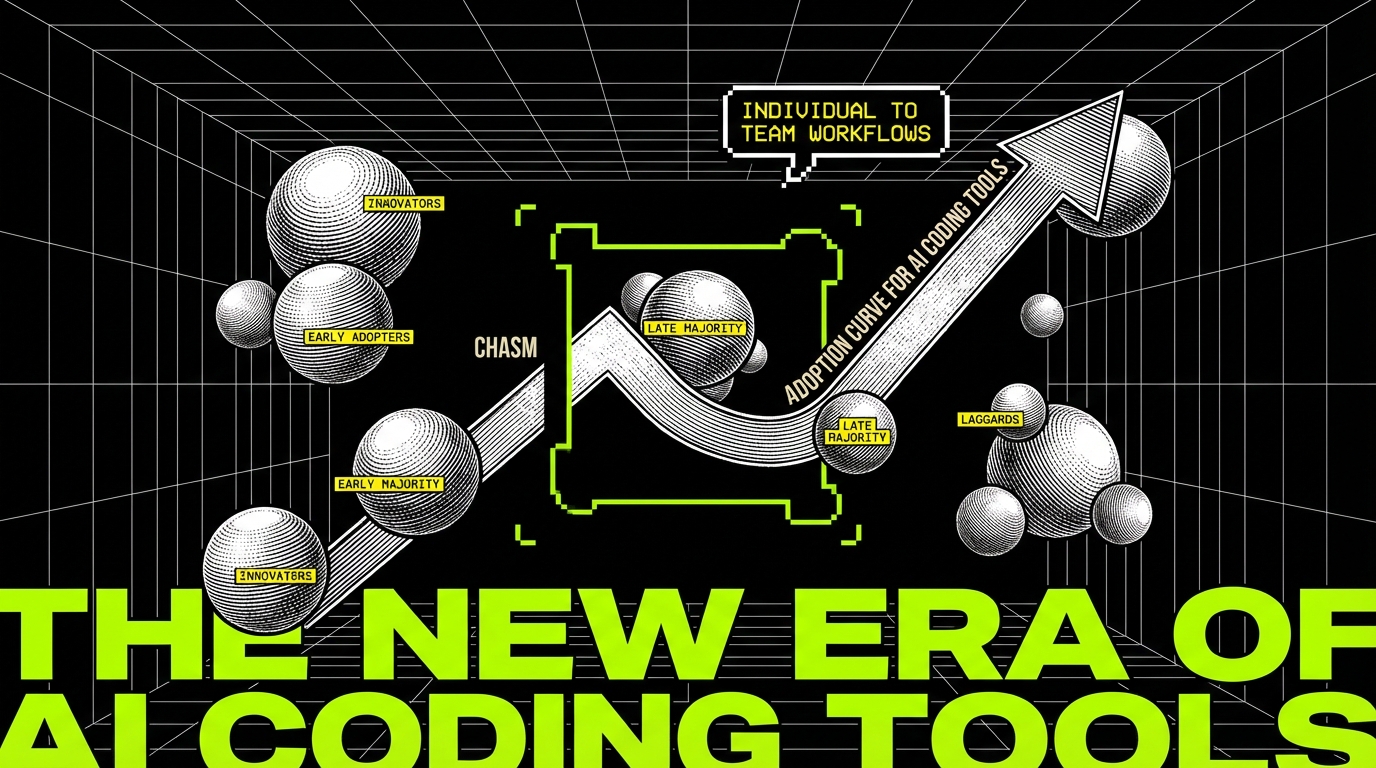

AI coding tools have a familiar adoption pattern. A few engineers try them early, ship a couple of quick wins, and tell everyone else. Then the rest of the team tries the same prompts and gets different results. One person sees clean diffs and faster reviews. Another gets broken builds and a week of cleanup.

This gap is not about intelligence. It is about environment. Early adopters can tolerate sharp edges because they control their scope, pick tasks that fit the tool, and patch mistakes fast. The early majority needs repeatability. They need predictable output, shared rules, and a way to recover when the tool is wrong.

At Apptension we see this most clearly when AI moves from a single developer’s workflow into delivery for a client product. The moment AI touches a shared repository, it becomes a systems problem: tooling, CI, code review, security, and ownership. If you want AI coding to “cross the chasm,” you have to treat it like any other production capability.

What “crossing the chasm” looks like in codebases

In software teams, the chasm shows up between individual productivity and team throughput. An early adopter can gain speed by generating boilerplate, tests, or refactors. The early majority asks a different question: will this reduce cycle time for the whole team without raising defect rates?

The chasm is also about trust. A single engineer can trust their own judgment when they accept or reject AI output. A team needs shared trust signals: tests, static analysis, review checklists, and a clear audit trail. Without those signals, AI output feels like an unbounded risk.

There is a third dimension: cost of mistakes. In a toy repo, a wrong suggestion is a minor annoyance. In a production codebase with CI gates, deployment pipelines, and compliance requirements, a wrong suggestion can burn hours across multiple roles. Early majority adoption happens when the cost of mistakes becomes bounded and visible.

Where AI coding helps (and where it reliably fails)

AI coding tools are good at generating plausible code. That sounds obvious, but “plausible” is not the same as “correct in your system.” They perform best when the task has strong local context and weak global coupling. They perform poorly when correctness depends on hidden constraints, runtime behavior, or subtle domain rules.

Teams cross the chasm faster when they stop debating “is AI good?” and start cataloging “which tasks are safe?” The goal is not to maximize AI usage. The goal is to maximize shipped value per unit of risk.

High win-rate tasks

Some tasks have a high success rate because they are constrained and easy to verify. They also tend to be the work that developers dislike but still must do. When you standardize these tasks, AI becomes a multiplier instead of a gamble.

- Boilerplate with strong patterns: CRUD handlers, DTOs, serializers, and route wiring when your project follows consistent conventions.

- Test scaffolding: generating test cases from existing functions, then editing assertions to match real behavior.

- Mechanical refactors: renames, extraction, and repetitive transformations when supported by type checks and tests.

- Documentation and examples: README snippets, usage examples, and inline comments that explain existing code.

In Apptension delivery work, the most consistent wins come from tasks with immediate feedback loops. If the change compiles, passes tests, and produces a small diff, review becomes faster. That is the kind of win a team can repeat.

Low win-rate tasks

Failures cluster around tasks that require deep system knowledge and non-obvious tradeoffs. The tool may still produce code that looks right, and that is the danger. The more “confident” the output sounds, the more likely it is to bypass a reviewer’s skepticism.

- Security-sensitive changes: auth flows, permission checks, token handling, and crypto primitives.

- Distributed systems behavior: retries, idempotency, ordering, and eventual consistency.

- Performance work: query planning, caching strategy, memory pressure, and load behavior.

- Domain rules: billing, compliance, data retention, and anything that is “correct because the business says so.”

AI output is easiest to accept when it is easiest to verify. Adoption stalls when verification is hard, slow, or depends on tribal knowledge.

From prompts to products: the missing layer is guardrails

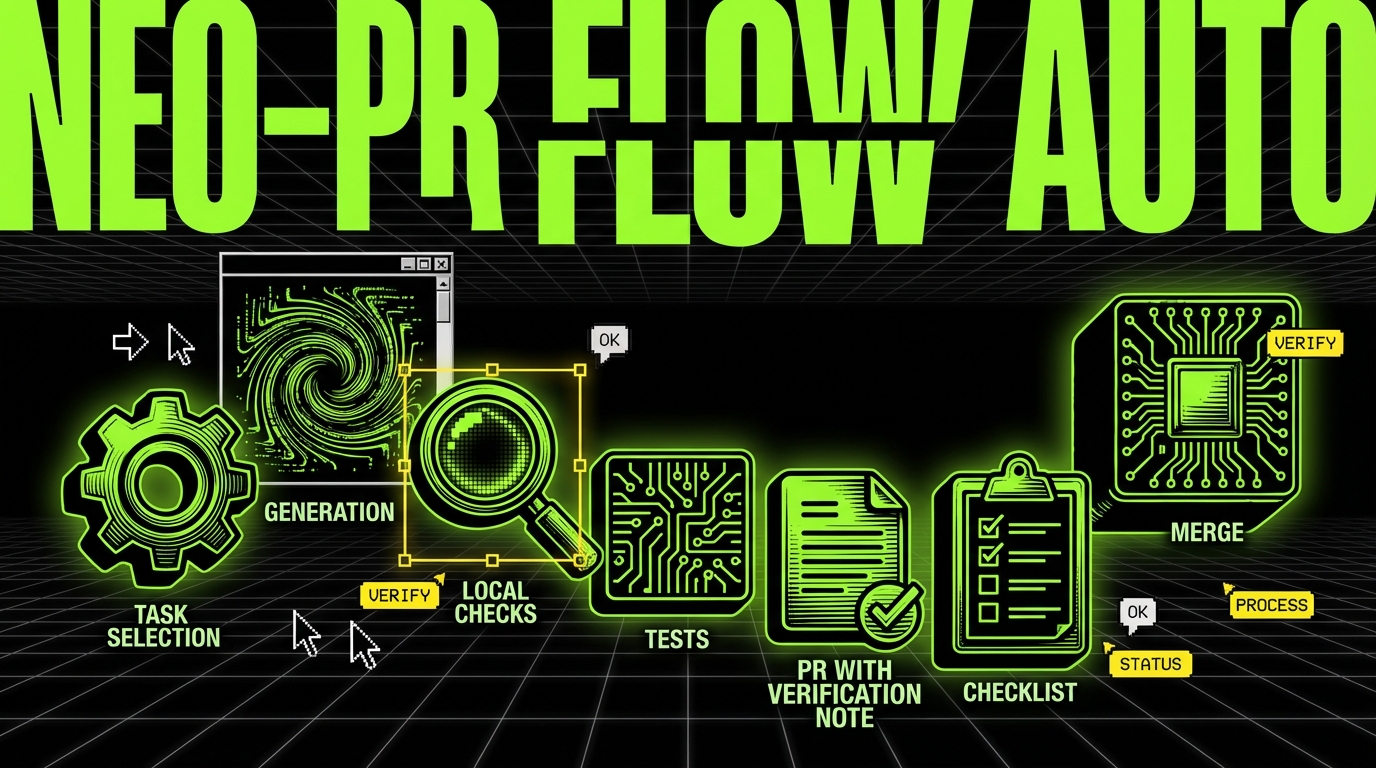

Early adopters treat AI like a smart autocomplete. The early majority needs a workflow. That workflow has to catch failures before they reach production, and it has to make success repeatable across engineers with different experience levels.

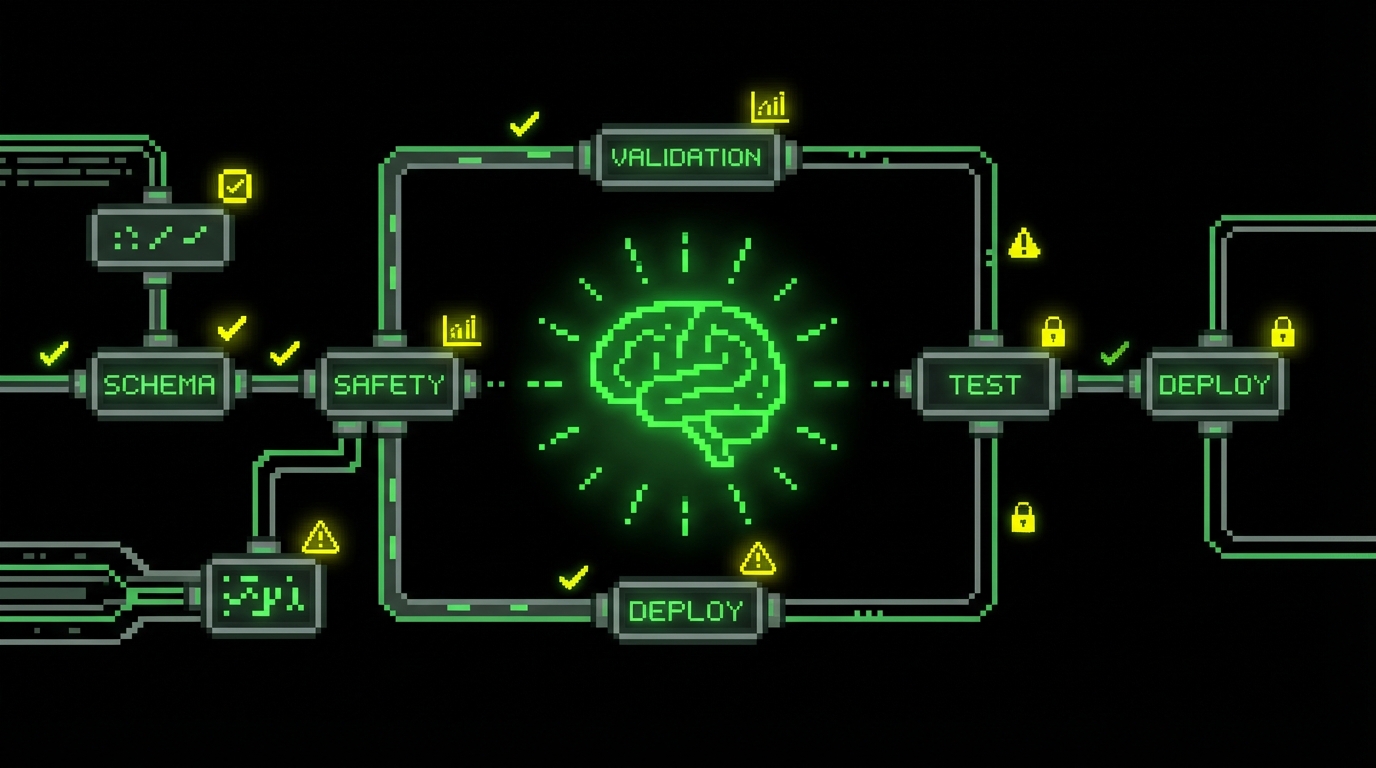

Guardrails are not a single tool. They are a set of constraints that shape AI usage. They also shift the team’s mindset from “prompt engineering” to “engineering with constraints,” which is how most production systems already work.

Repository-level constraints

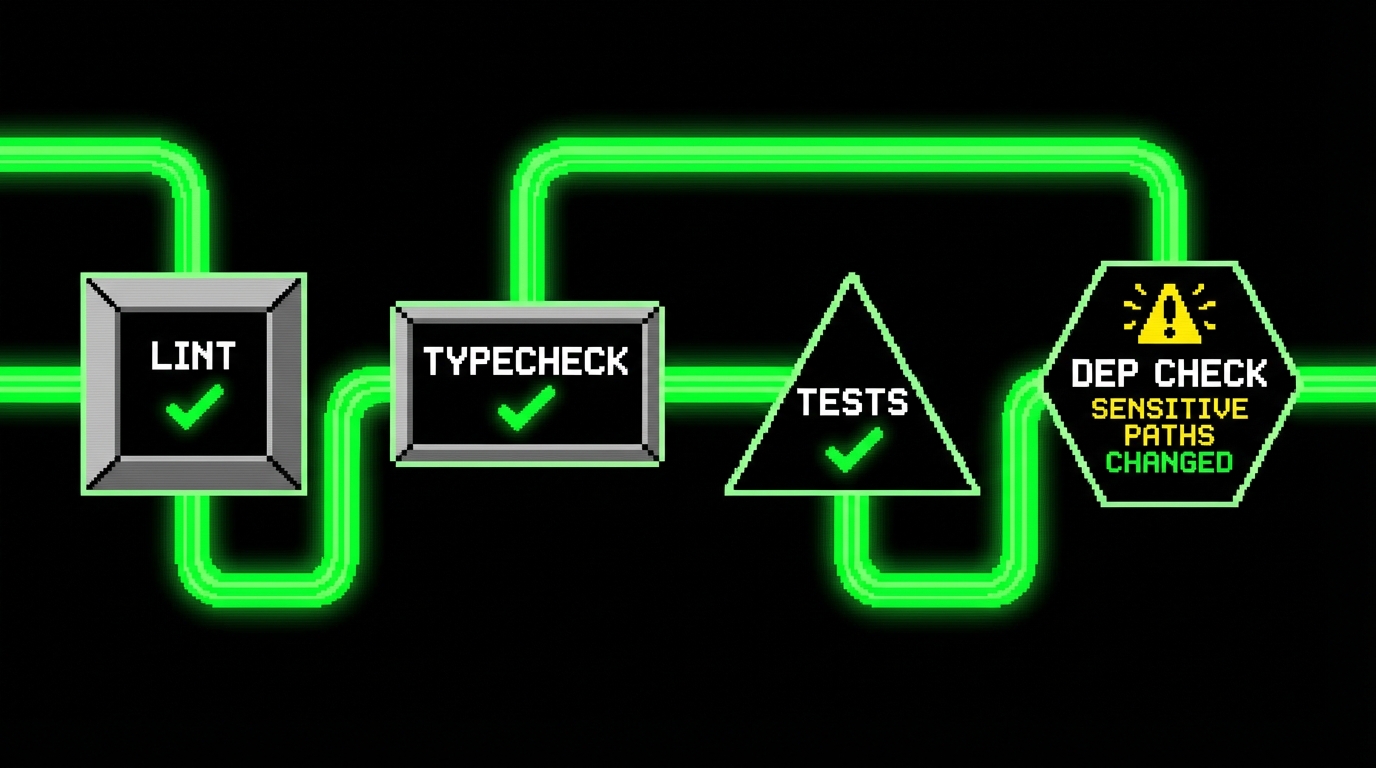

The fastest way to reduce AI risk is to tighten the definition of “done.” If your CI is permissive, AI will happily generate code that compiles locally but fails later. If your CI is strict, AI becomes safer because the tool must pass the same gates as humans.

Useful constraints include formatting, linting, type checks, and test thresholds. They also include dependency rules, such as banning new packages without review. When these constraints exist, AI can generate code, but it cannot silently change the shape of your system.

- Fail builds on type errors and lint violations.

- Require tests for changed modules, not just overall pass status.

- Block new dependencies unless explicitly approved.

- Enforce small PRs with clear descriptions of intent.

Human-level constraints

Even strong CI does not catch everything. Teams still need review norms that match AI-assisted development. The key is to review intent and invariants, not just syntax. If the PR author cannot explain why the change is safe, the change is not safe.

We have seen teams improve outcomes by adding a simple rule: AI-generated code must come with a short “verification note.” It lists what the author checked and what could still be wrong. This sounds bureaucratic, but it reduces back-and-forth in review and keeps risk visible.

Implementation playbook: adopting AI coding in a team

Crossing the chasm requires more than buying seats. You need a rollout plan that treats AI like any other developer tool that can change output quality. A plan also prevents the “silent split” where a few people use AI heavily and others avoid it, which makes code style and review expectations inconsistent.

The playbook below fits both product teams and delivery teams. It also fits PoC and MVP work, where speed matters, but rework hurts. At Apptension, rapid prototyping only works when we keep diffs reviewable and keep the build green. AI can help, but only inside a tight loop.

Step 1: define safe scopes and banned scopes

Start with a written list. It can be short, but it must be explicit. The early majority will not adopt a tool if they fear they will be blamed for using it “wrong.” A scope list makes expectations clear and reduces anxiety.

- Pick 3 - 5 safe task types (tests, scaffolding, small refactors).

- Pick 3 - 5 banned task types (auth, payments, infra changes).

- Define an escalation path for exceptions (who approves, what evidence is needed).

Revisit this list monthly. Teams often discover that some “banned” tasks become safe once verification improves. The reverse also happens when a tool update changes behavior.

Step 2: standardize context injection

AI tools fail when they lack context, and they hallucinate when they guess. You can reduce guessing by standardizing what you provide: relevant files, API contracts, and examples of existing patterns. This is not about longer prompts. It is about the right artifacts.

A simple tactic is a project “AI brief” checked into the repo. It describes architecture, folder conventions, testing approach, and key invariants. Engineers can paste sections into prompts or attach it as context in tools that support it.

- Folder structure and naming rules.

- Preferred patterns (for example, dependency injection style).

- Testing stack and conventions.

- Do-not-touch modules and why.

Step 3: make verification cheap

The early majority adopts tools that save time end to end, not tools that shift time into debugging. Verification must be fast. If tests take 40 minutes, AI will increase frustration because iteration becomes slow. If tests take 5 minutes, AI becomes easier to trust.

Invest in test parallelization, smaller test suites, and local developer experience. This is not “AI work,” but it is what makes AI practical. In long-running products, this investment pays off even if AI adoption stalls, which makes it a safe bet.

Concrete patterns: AI-assisted coding with TypeScript and CI

Code examples help because they show where AI fits into a normal workflow. The goal is not to let AI write everything. The goal is to constrain input and verify output with automation.

Below are three patterns we see teams adopt. Each keeps AI in a narrow lane. Each also produces artifacts that reviewers can trust: small diffs, tests, and clear boundaries.

Pattern 1: generate a typed API client from an OpenAPI spec

Instead of asking AI to “write an API client,” generate one from a spec and let AI help with integration and usage examples. This reduces ambiguity. It also prevents subtle mismatches between frontend and backend types.

In a TypeScript codebase, a generated client gives you compile-time checks. AI can still help write a wrapper or a hook, but the underlying contract stays consistent.

// pnpm add -D openapi-typescript

import fs from "node:fs";

import openapiTS from "openapi-typescript";

async function main() {

const spec = JSON.parse(fs.readFileSync("./openapi.json", "utf8"));

const types = await openapiTS(spec);

fs.writeFileSync("./src/api/schema.d.ts", types);

}

main().catch((e) => {

console.error(e);

process.exit(1);

});This script makes the contract explicit. AI can then generate code that consumes schema.d.ts and TypeScript will reject mismatched fields. Reviewers also get a clean diff: spec changes plus generated output.

Pattern 2: add an “AI change” checklist to PR templates

This is not code that runs in production, but it is still an implementation detail. It makes verification visible. It also helps new team members learn what “safe AI usage” looks like in your repo.

## AI-assisted changes (fill if applicable) - [ ] I can explain the change without referencing the tool output - [ ] I ran: unit tests / typecheck / lint - [ ] I added or updated tests for the behavior change - [ ] Risk notes (what might still be wrong):The checklist does not prevent mistakes by itself. It reduces silent failures by forcing the author to state what they verified. It also gives reviewers a consistent place to look for risk.

Pattern 3: CI gate for new dependencies and risky paths

AI tools often propose “just add a library” because that is common in generic examples. In mature codebases, uncontrolled dependencies increase attack surface and maintenance cost. A simple CI check can flag new packages or changes in sensitive folders.

import fs from "node:fs";

const before = JSON.parse(fs.readFileSync("./package.before.json", "utf8"));

const after = JSON.parse(fs.readFileSync("./package.json", "utf8"));

const deps = (p: any) => ({

..(p.dependencies || {}),

..(p.devDependencies || {})

});

const added = Object.keys(deps(after)).filter((k) => !(k in deps(before)));

if (added.length) {

console.error("New dependencies added:", added.join(", "));

process.exit(1);

}This kind of gate is blunt, but it is effective. Teams can add an override path for approved changes. The point is to stop accidental drift, especially when AI suggests dependencies that do not match your stack.

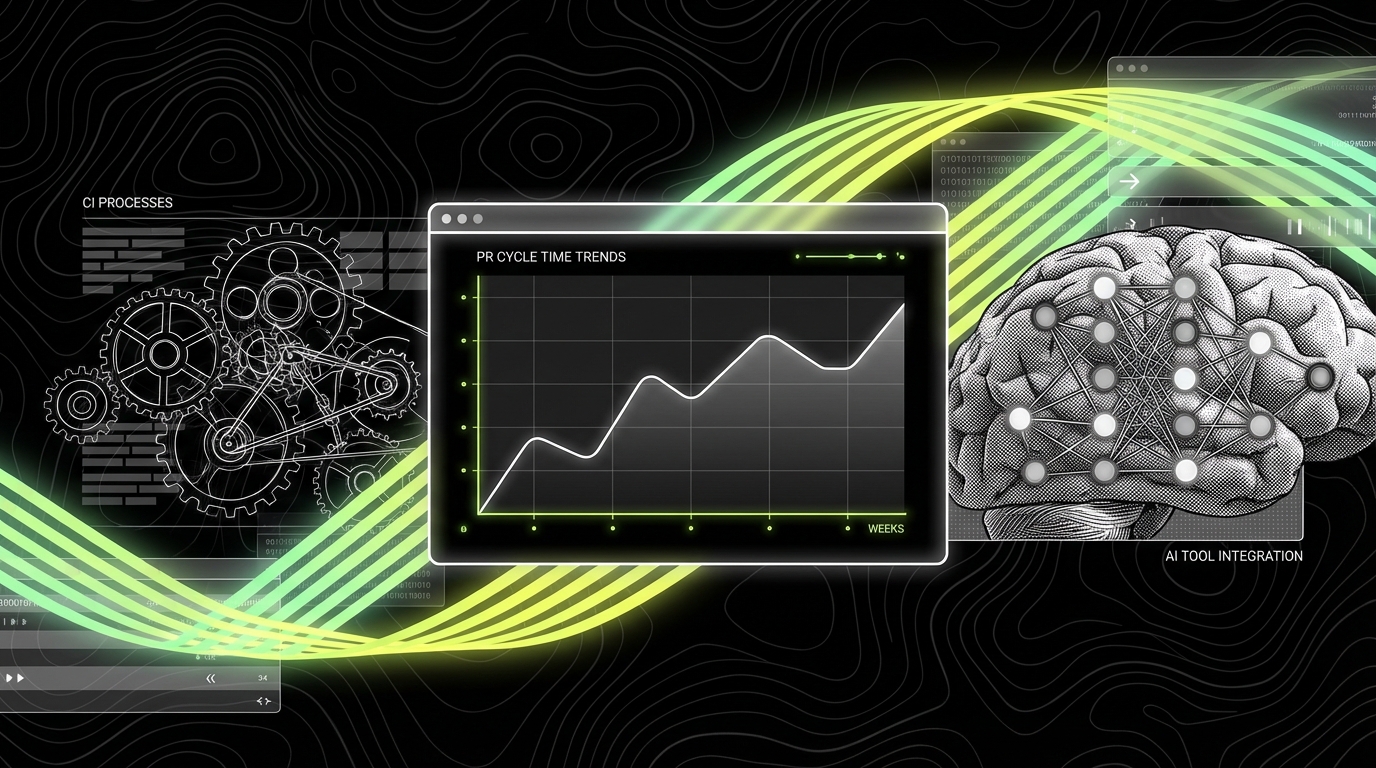

Measuring success: what to track beyond “it feels faster”

Early adopters report speed because they feel it in their own flow. The early majority needs evidence at the team level. If AI saves one developer 30 minutes but adds two hours of review and rework, the net effect is negative.

You do not need complex analytics to start. You need a few metrics that connect to delivery outcomes. The point is to detect regressions early and to keep discussions grounded in observable data.

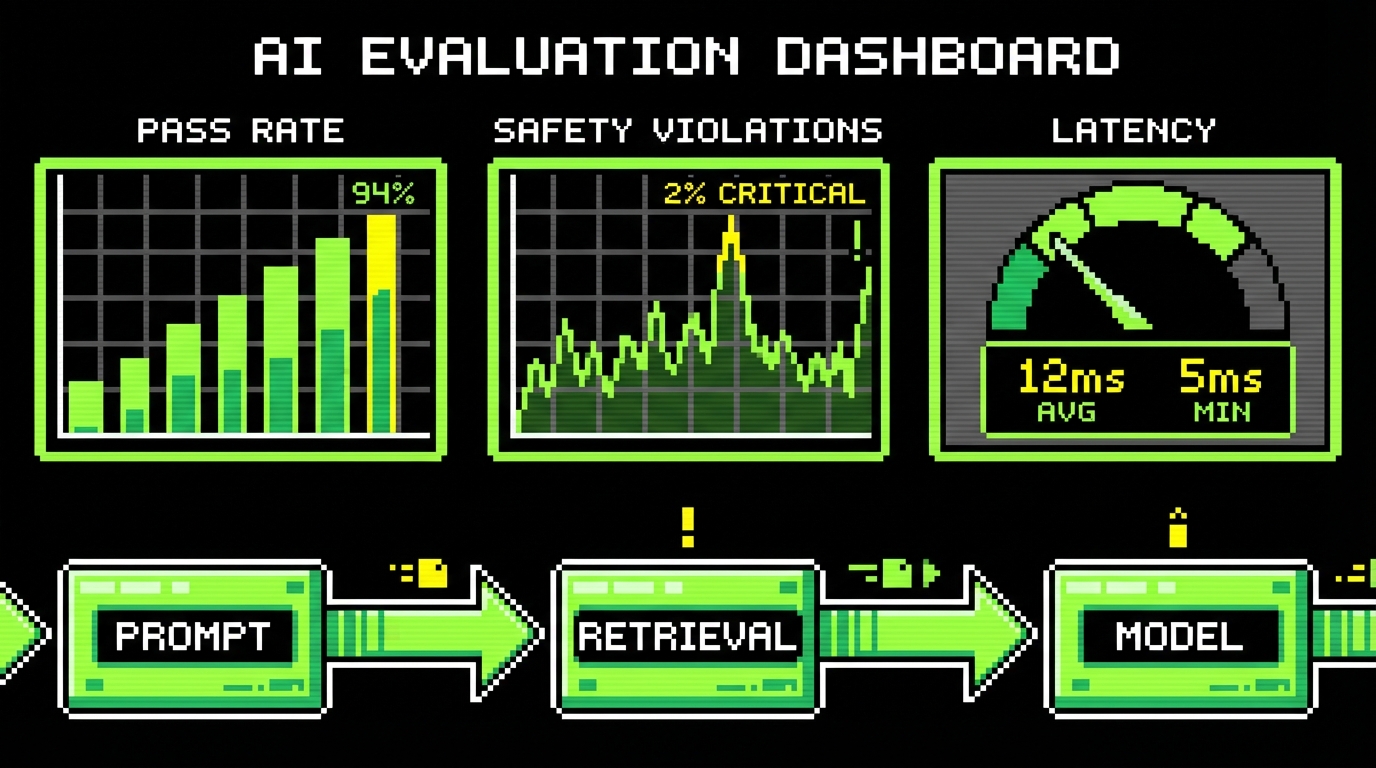

Practical metrics for AI-assisted development

Pick metrics you can collect with existing tools: Git hosting, CI, and issue trackers. Track them over a few weeks, not a single sprint. AI adoption changes behavior gradually, and the first week often includes setup cost.

- PR cycle time: time from first commit to merge, split by PR size.

- Review rounds: number of review iterations before approval.

- CI failure rate: percent of PRs that fail at least one CI job.

- Defect leakage: bugs found after release that map to recent AI-assisted areas.

- Revert rate: how often changes get reverted within 7 days.

In long partnerships, like our “861 - 2 Years” data management work, stability matters as much as speed. Continuous value usually comes from fewer regressions and predictable delivery. AI can support that, but only if it does not increase defect leakage.

Qualitative signals that matter

Some important signals are not numeric. They show up in how engineers talk during review and incidents. If the team starts saying “the tool wrote it” as a defense, you have an accountability problem. If reviewers start ignoring diffs because “it’s probably fine,” you have a quality problem.

If AI reduces ownership, it increases risk. The fix is not banning AI. The fix is making ownership explicit in the workflow.

Conclusion: make AI boring, then make it common

AI coding crosses the chasm when it becomes boring. Boring means predictable. It means the team knows where it fits, how to verify output, and how to recover when it fails. Early adopters can live with surprises. The early majority will not.

The practical path is clear: define safe scopes, standardize context, and invest in fast verification. Add CI gates that prevent silent drift. Make reviewers focus on intent and invariants. Track a small set of metrics that reflect team throughput and quality.

If you are building a PoC or MVP, AI can help you move faster, but only if you keep the loop tight: small diffs, strict checks, and clear ownership. That is the same discipline that keeps prototypes from collapsing when they become products. Once that discipline is in place, wider adoption stops being a debate and starts being a normal tool choice.