AI assisted coding sits in an awkward middle. Some teams treat it like a new kind of editor that makes them faster and shifts attention to architecture. Other teams see a debt machine that produces plausible code with unclear provenance. Both groups are reacting to real signals in day to day work.

This is not a culture war between “progress” and “complaining.” It is a quality mechanism. If AI tools cannot satisfy the skeptics’ demands, they will stall at pilots and side projects. If they can, they will become boring infrastructure, like CI or code review.

At Apptension we see this split inside the same delivery teams. One engineer uses an assistant to draft a test harness in minutes. Another has to unwind a subtle auth bug caused by a confident but wrong suggestion. The path forward is not to pick a side. It is to make the risks measurable and the controls enforceable.

Crossing the Chasm, but for code generation

“Crossing the Chasm” describes how products move from enthusiasts to the early majority. Enthusiasts accept sharp edges because they enjoy the advantage. The early majority wants predictable outcomes, clear failure modes, and support when things go wrong. AI assisted coding is currently optimized for enthusiasts: fast prompts, fast output, and a dopamine loop of “it compiled.”

The early majority asks different questions. Who owns the output? Can we audit it? What happens when the model changes next month? Can we prove we did not copy licensed code into a proprietary repo? Those questions are not philosophical. They are procurement questions, legal questions, and incident response questions.

In practice, adoption stalls when the tool cannot fit into existing quality gates. Teams already have mechanisms like code review, CI, SAST, dependency scanning, and release approvals. AI output must pass through those same gates, and sometimes needs new ones. The chasm is not about model quality alone. It is about operational fit.

Enthusiasts vs skeptics: what each group sees

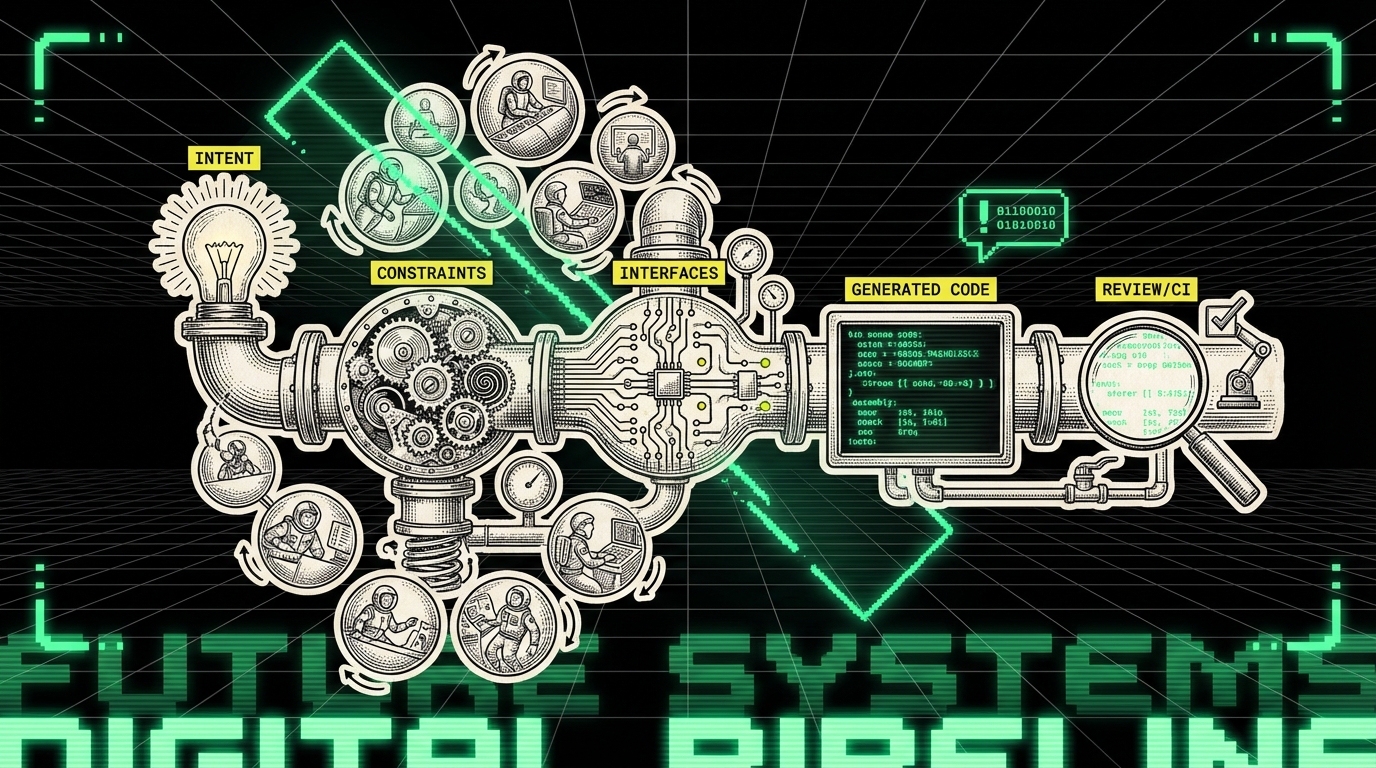

Enthusiasts see a shift in the shape of work. They spend more time describing intent, constraints, and interfaces. They generate boilerplate, migrations, and tests faster. They also explore unfamiliar APIs with less friction, which matters in polyglot stacks.

Skeptics see a different pattern. They see code that “looks right” but hides edge cases. They see security checks bypassed because the assistant optimized for passing tests, not for threat models. They see a maintainability tax: more code, more surface area, and more to review under time pressure.

Both views can be true in the same sprint. The deciding factor is whether the team has guardrails that turn AI output into reviewed, testable, owned code. Without guardrails, the assistant becomes a multiplier for whatever your team already struggles with.

What enthusiasts get right: architecture first, code second

When AI works well, it changes the sequence of decisions. Engineers start with contracts, invariants, and data shapes. They use the assistant to draft the obvious parts and keep humans focused on the hard parts. That is a healthy shift, because most production bugs come from unclear assumptions, not from typos.

This approach also fits how modern systems are built. Many teams already rely on scaffolding tools, code generators, and templates. AI is another generator, but it can adapt to a codebase and a style guide when guided correctly. The benefit is not “writing code faster.” The benefit is reducing the time between a decision and a working slice of software.

In Apptension delivery, the best results show up in thin vertical slices. For example, when building AI features like the L.E.D.A. retail analytics tool in 10 weeks, the time pressure is real. Assistants can help draft ingestion adapters, API clients, and test data builders. But the wins come only after we lock down interfaces and acceptance criteria.

Practical patterns that keep humans in control

Enthusiast teams tend to use AI in patterns that reduce risk. They ask for small deltas, not whole subsystems. They request explanations, tradeoffs, and tests, not just code. They treat the assistant as a junior contributor that needs tight tasks and strong review.

These patterns are boring, which is the point. They make AI output legible. They also make it easier to spot when the assistant is inventing APIs, skipping error handling, or making unsafe defaults.

- Start from contracts: define request and response types, database schema, and error codes before generating handlers.

- Ask for tests first: generate failing tests that describe behavior, then implement until they pass.

- Constrain scope: “Modify these 20 lines” beats “Rewrite the module.”

- Require citations to codebase: “Point to existing patterns in this repo” reduces random style drift.

Example: generate a narrow, testable change

The safest AI assisted work often looks like a normal refactor. You define the behavior, then you ask for a small patch. Below is a TypeScript example that makes a common rule explicit: never trust user provided redirect URLs. The assistant can draft it, but the team owns the decision and the review.

export function safeRedirect(target: string, allowedHosts: string[]): string {

try {

const url = new URL(target);

if (!allowedHosts.includes(url.host)) return "/";

if (url.protocol !== "https:") return "/";

return url.pathname + url.search;

} catch {

return "/";

}

}This code is short, but it encodes a security posture. It rejects non HTTPS URLs, unknown hosts, and malformed input. The key is not the function itself. The key is that the behavior is explicit, reviewable, and can be covered by unit tests.

What skeptics get right: AI can amplify debt and risk

Skeptics are not “anti AI.” They are reacting to failure modes that teams already know: unclear ownership, hidden coupling, and security regressions. AI makes these worse because it can produce a lot of code quickly, and it produces code that looks confident. That combination can overwhelm review bandwidth.

Technical debt is not just messy code. It is future work created by today’s shortcuts. AI can create debt by copying patterns that do not fit your system, by adding layers you do not need, or by missing non functional requirements like observability and rate limiting. The code compiles, the PR merges, and then the pager goes off later.

Security risk is similar. Assistants often default to permissive behavior: broad CORS settings, weak input validation, or naive crypto. They may also generate code that depends on outdated libraries. If you do not run the same scanners and reviews you already trust, you will ship vulnerabilities faster.

Maintainability failure modes we see in real repos

Maintainability issues tend to show up weeks after the merge. The assistant may introduce a new abstraction that only it understands. Or it may duplicate logic instead of reusing existing helpers, because it did not “feel” the cost of duplication. Over time, you get more code paths that do the same thing slightly differently.

Another common issue is error handling. AI generated code often handles the happy path and logs an error, but it does not classify errors, propagate them consistently, or attach context. In distributed systems, that becomes a debugging tax. The system fails, but the traces do not tell you why.

- Duplication drift: similar helpers with different edge case behavior.

- Abstraction creep: extra layers that hide simple logic.

- Inconsistent errors: mixed error shapes and missing context.

- Observability gaps: no metrics, weak logs, missing trace spans.

Security and compliance: the “who signed off” question

For regulated industries, the problem is not only vulnerabilities. It is auditability. Someone needs to answer “who wrote this” and “why is it safe.” If the answer is “the model suggested it,” that is not acceptable. You need a human sign off trail and a repeatable process that shows due diligence.

License provenance is another practical concern. Even if your tool claims it avoids verbatim training data output, legal teams will ask what guarantees exist, how they are tested, and what happens if a claim arrives. The early majority wants contractual clarity, not a blog post.

AI crosses into the early majority when it can be audited like any other supplier: inputs, outputs, controls, and an escalation path when it fails.

Guardrails that let AI scale beyond enthusiasts

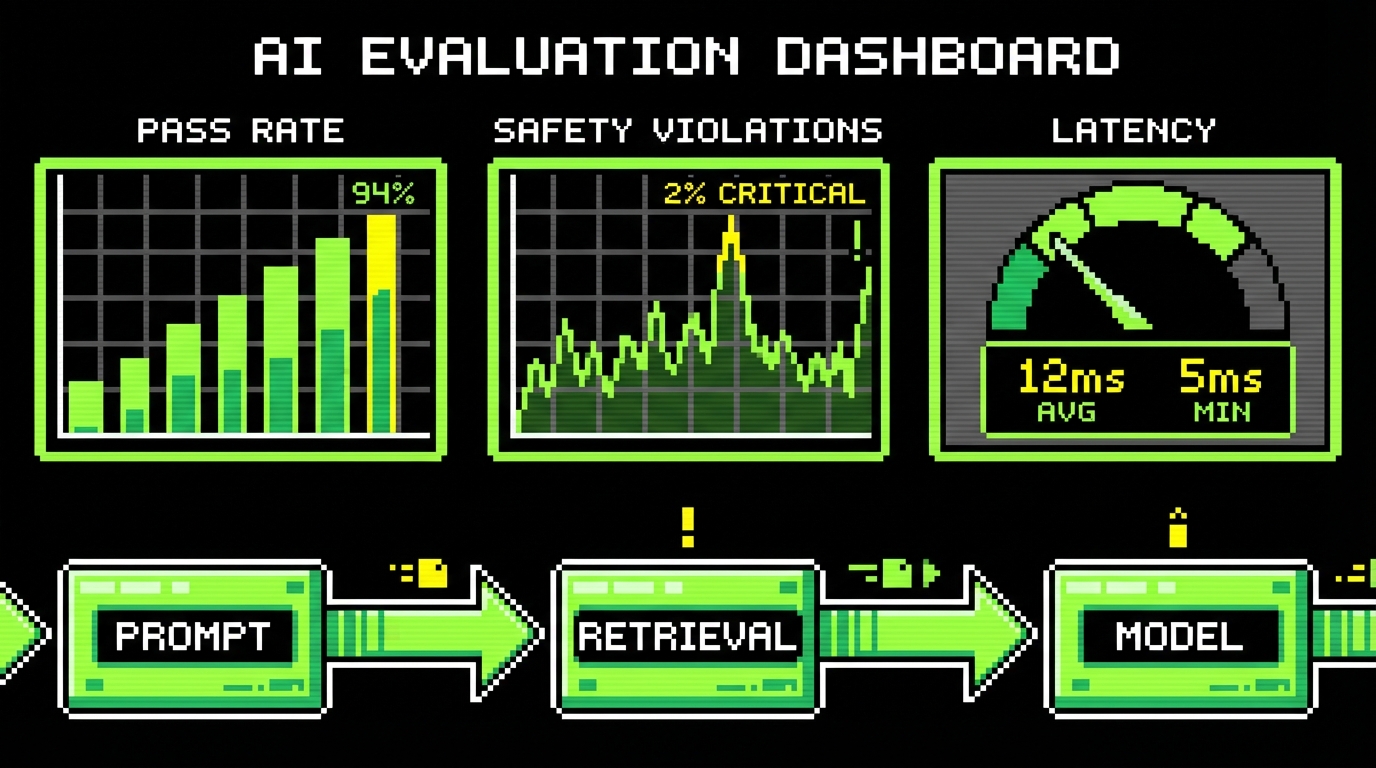

Guardrails are not a single tool. They are a set of constraints that make unsafe behavior hard and safe behavior easy. Most teams already have some of them. The missing piece is to adapt them for AI generated code, where volume is higher and authorship is fuzzier.

Start by treating AI output as untrusted until proven otherwise. That sounds harsh, but it matches how we treat user input, third party dependencies, and infrastructure changes. You can still move fast. You just move fast inside a pipeline that catches common failures.

In Apptension projects, we aim for guardrails that do not rely on hero reviewers. We want checks that run in CI, policies that block merges, and templates that steer engineers toward safe defaults. This matters when teams grow or when deadlines compress, because review quality otherwise drops.

Baseline controls: what to add before you expand usage

If your team is experimenting, you can start with a short checklist. If you plan to scale, you need automated gates. Below is a baseline set that tends to cover the most frequent failure modes without slowing teams to a crawl.

- Mandatory tests for AI touched code: unit tests for logic, integration tests for boundaries.

- SAST and dependency scanning in CI: block known critical issues on merge.

- Secret scanning: prevent tokens and keys from landing in git history.

- Threat model prompts for sensitive areas: auth, payments, PII, file uploads.

- Review checklist: input validation, error handling, logging, and rate limiting.

These controls are not “AI specific.” That is a feature. The goal is to make AI fit your existing engineering system. When controls are special cased, they get skipped under pressure.

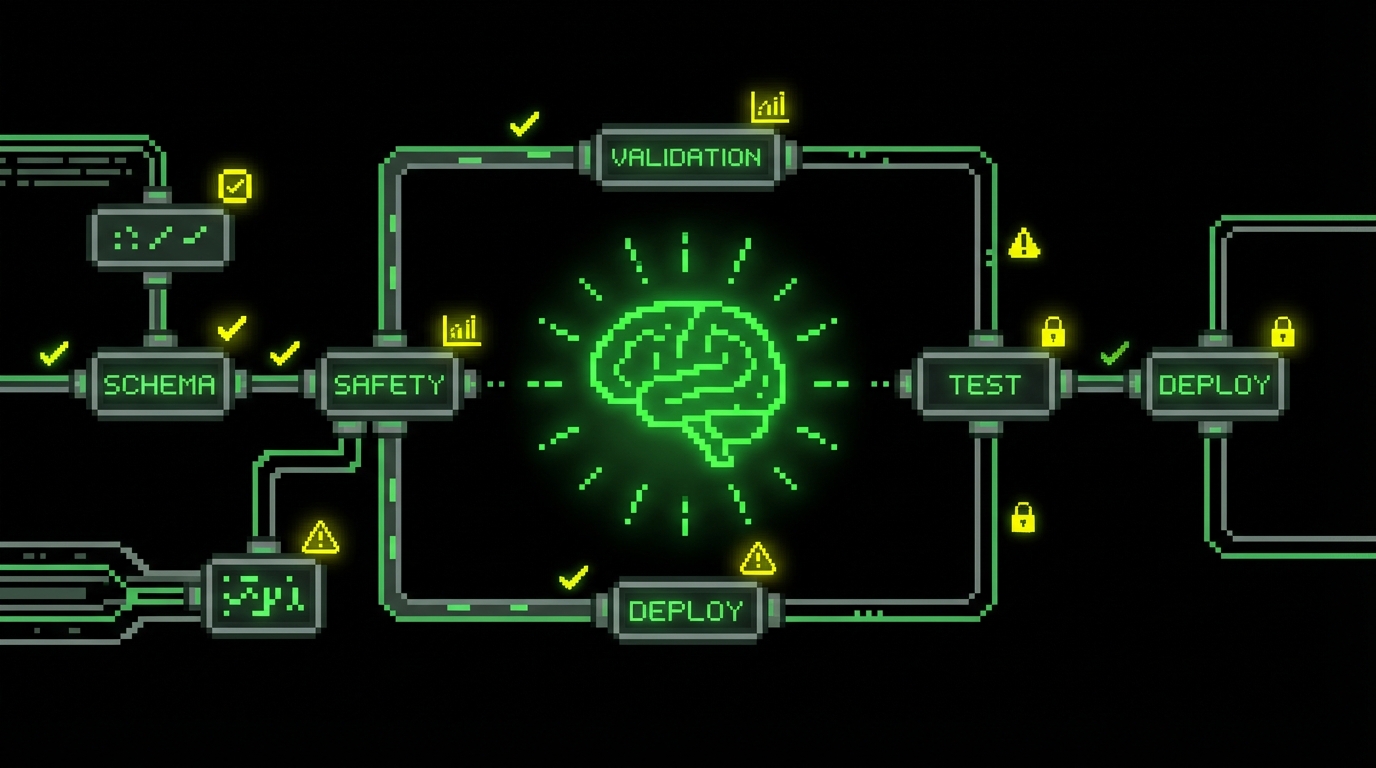

Example: CI policy that blocks risky patterns

Policy as code is one way to make skeptics comfortable. You encode rules that are easy to argue about. The assistant can still generate code, but the pipeline rejects known unsafe patterns. Below is a simple example using Semgrep rules to block common mistakes in Node services.

rules: - id: no-eval message: "Do not use eval()" severity: ERROR languages: [javascript, typescript] patterns: - pattern: eval(..) - id: no-insecure-random message: "Do not use Math.random() for tokens" severity: ERROR languages: [javascript, typescript] patterns: - pattern: Math.random()This is not complete security. It is a tripwire. It catches the sort of “works in a snippet” code that assistants often produce. It also turns a debate into a concrete diff: if you need an exception, you document it.

Audits, SLAs, and upgrade paths: what the early majority asks for

Enthusiasts can live with a tool that changes behavior between releases. The early majority cannot. They need stable contracts: what data leaves the org, how it is stored, who can access it, and what happens when the vendor changes models or pricing. Without that, adoption stays informal and fragmented.

Think of this as supply chain management for code. You already ask these questions of cloud providers and payment processors. AI coding assistants are now part of the same chain. If they touch proprietary code, they are in scope for security review and vendor risk assessment.

In delivery work, this often becomes the turning point. A team may love the productivity boost, but the security team blocks rollout until there is an audit report, a data handling statement, and a clear opt out for training. The right response is not to bypass security. It is to meet the bar with evidence.

What “auditability” looks like in practice

Auditability is a set of artifacts and logs. You want to be able to reconstruct what happened when a risky change was introduced. You also want to show that you had controls in place and that humans approved the result.

- Prompt and completion retention policy: what is stored, for how long, and where.

- Access controls: who can use the assistant, from which machines, with which repos.

- Change attribution: PR metadata that marks AI assisted changes for sampling and review.

- Model version tracking: which model produced suggestions for a given period.

This does not mean storing every prompt forever. In many environments that would be a liability. It means having a defensible policy and the ability to investigate incidents when they happen.

Upgrade paths and “model drift” as an engineering problem

Model drift is not only about accuracy. It is about behavior. A new model version may produce different code for the same prompt, or it may prefer different libraries. That can create inconsistency across a codebase, which raises maintenance costs.

Teams can manage this the same way they manage dependency upgrades. Pin versions where possible. Run canary periods. Track output changes in a controlled environment. If your vendor cannot support this, skeptics will keep winning the argument, and for good reasons.

If you cannot describe your upgrade plan for the assistant, you do not have an assistant. You have a moving dependency you cannot test.

How to decide where you sit: a practical self assessment

“Are you an enthusiast or a skeptic” is a useful question only if it leads to action. Most teams are both, depending on the area of the system. You might be enthusiastic about scaffolding UI components and skeptical about auth flows. That is a rational split.

A better question is: what is the cost of being wrong? If the assistant generates a slightly messy admin page, you can clean it up later. If it generates a broken access control check, you may have a breach. Adoption should follow risk, not excitement.

Below is a simple rubric we use when advising teams on where AI fits. It is not perfect, but it forces explicit choices and makes tradeoffs visible.

Rubric: match AI usage to risk and review capacity

Score each area from 1 to 5. Higher risk means more guardrails or no AI usage. Higher review capacity means you can safely accept more AI generated volume. The goal is to avoid the worst combination: high risk, low review.

- Data sensitivity: PII, payments, health data, internal secrets.

- Blast radius: can a bug affect all users or a small segment.

- Change frequency: code that changes often needs consistency.

- Test coverage: do tests catch regressions or not.

- Reviewer bandwidth: can reviewers read and reason about the diff.

When the scores are high risk and low coverage, restrict AI to documentation, test data setup, or refactors with strict checks. When the scores are low risk and high coverage, you can be more permissive and still sleep at night.

Example: “AI allowed” checklist for a PR description

One low friction tactic is to make expectations explicit in the PR template. This helps reviewers and it nudges authors to do the right work before asking for approval. It also avoids moral debates about whether AI is “allowed.” The question becomes whether the change meets the bar.

### AI assisted change - [ ] I verified inputs are validated and errors are handled consistently - [ ] I added or updated tests that fail without this change - [ ] I ran security and dependency checks locally or in CI - [ ] I did not paste secrets, tokens, or customer data into prompts - [ ] I can explain the change without referencing the assistantThe last checkbox matters more than it looks. If the author cannot explain the change, the team does not own it. That is how maintainability dies, one merge at a time.

Conclusion: skeptics are the bridge, not the blocker

AI assisted coding will not become normal because enthusiasts are excited. It will become normal when skeptics stop finding sharp edges that hurt reliability, security, and maintenance. That is not pessimism. It is how engineering improves: someone points at failure modes, and the system adapts.

If you are enthusiastic, treat that energy as fuel for building guardrails. Invest in tests, CI policies, and clear contracts. Push vendors for audit artifacts and stable upgrade paths. If you are skeptical, turn your concerns into concrete requirements and measurable checks, not blanket bans.

Where you sit today can change by subsystem, by team maturity, and by your controls. The chasm is not crossed by arguing. It is crossed by shipping code that stays safe and readable six months later, even when the assistant is turned off.