In 2026, “AI-assisted development” mostly means one thing: you type less boilerplate and you review more. The assistant sits inside the editor, in the terminal, and in your pull requests. It suggests code, writes tests, and drafts migration scripts. Then it confidently gets details wrong.

Teams that ship reliably treat the assistant like a fast junior engineer with a huge memory and no context. They give it constraints, they keep the diff small, and they run checks that do not lie. Teams that skip those steps get noisy PRs, brittle code, and security regressions that look fine at review time.

At Apptension we see the same pattern across SaaS and data management builds. AI helps most when the project already has a clear architecture, strict lint rules, and strong CI. It helps least when requirements are fuzzy or the system has hidden constraints. The rest of this article is a practical map of what to adopt, what to avoid, and how to wire it into a real delivery pipeline.

Where AI helps in 2026 (and where it still wastes time)

The best use cases are narrow and repeatable. Think: generating CRUD endpoints that match an existing pattern, writing unit tests from a spec, translating a data mapping table into code, or drafting a migration with constraints spelled out. In those cases, the assistant acts like autocomplete with longer memory, and the output is easy to verify.

The worst use cases are open ended design tasks where correctness depends on business rules scattered across tickets, Slack threads, and old PR comments. The assistant will fill gaps with plausible defaults. That looks productive until you hit edge cases in production. The cost shows up later as bug triage, not during generation.

In practice, we see these tasks land in the “good” bucket:

- Mechanical refactors: rename a field across a codebase, update imports, split a module while keeping public APIs stable.

- Test scaffolding: generate unit test structure, fixtures, and table driven cases from a short spec.

- Glue code: adapters between SDKs, DTO mapping, request validation, and error shaping.

- Docs that match code: README updates, runbooks, and API usage examples when generated from source.

And these tasks still often go wrong:

- Security sensitive code: auth flows, token validation, crypto, and permission checks. The assistant tends to “make it work” instead of “make it safe.”

- Distributed systems behavior: retries, idempotency, ordering, and backpressure. The assistant rarely models failure modes well.

- Performance work: query planning, caching strategy, memory pressure, and stream processing. It can suggest common tricks, but not the right tradeoffs.

AI output is cheap. Review time is not. Treat every generated line as a liability until tests and constraints make it boring.

Tooling stack in 2026: editor agents, PR bots, and local models

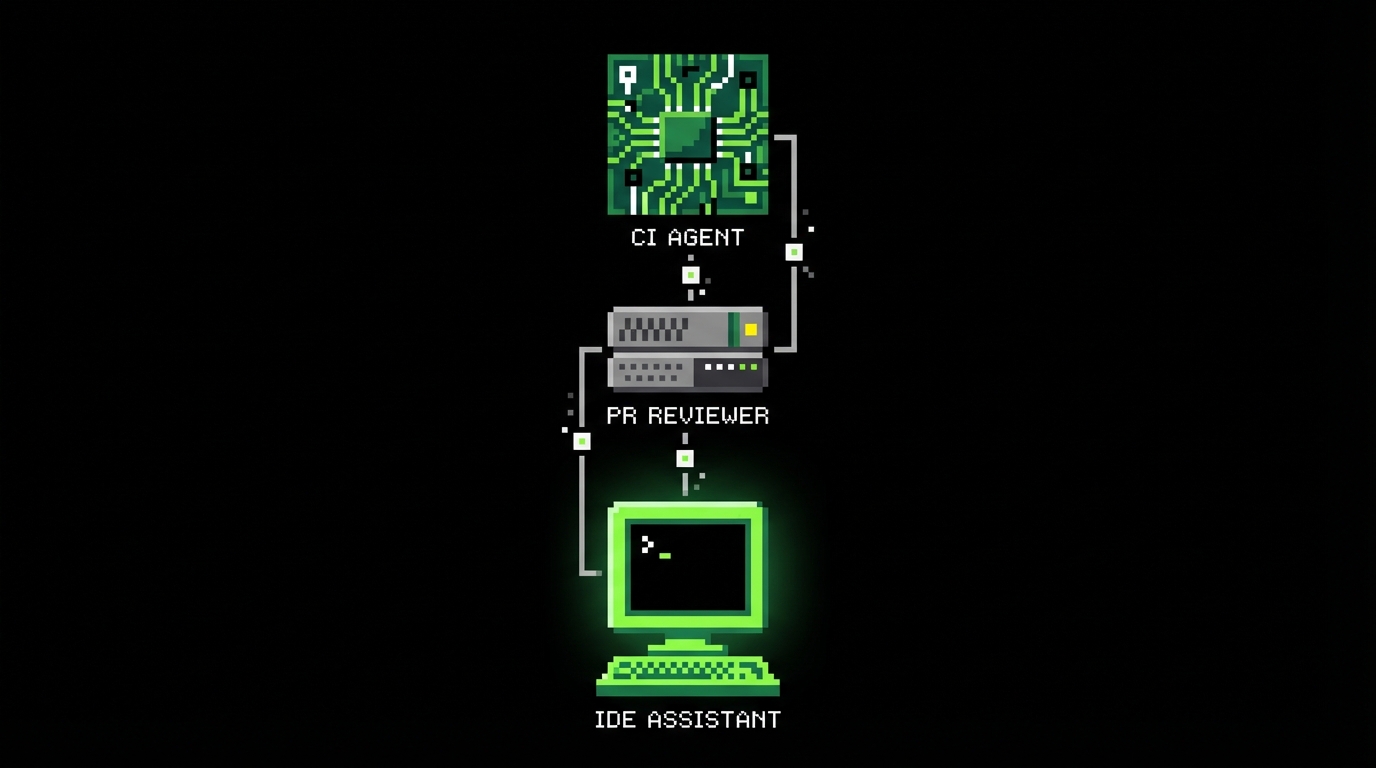

The 2026 stack usually has three layers. First, an editor assistant for tight feedback while you code. Second, a PR level agent that comments on diffs, suggests changes, and enforces style. Third, a “back office” agent that can run in CI to generate reports, update changelogs, or propose dependency bumps.

Most teams mix hosted models with local ones. Hosted models handle long context and broad knowledge. Local models handle sensitive code and fast iteration. The split is not ideological. It is about latency, cost, and data exposure. A common pattern is “local by default, hosted by exception.”

Editor workflows that stay predictable

Editor agents work best when they are constrained by the project’s own conventions. That means the assistant reads your ESLint rules, TypeScript config, folder structure, and existing patterns. If it does not, you get code that compiles but does not fit the codebase, which increases review friction.

We standardize a few “prompt macros” inside repos. They are short, but strict: expected file paths, error handling conventions, logging format, and how to write tests. The goal is to remove ambiguity. Ambiguity is where assistants invent behavior.

PR bots that check more than style

PR review agents in 2026 do more than nitpick formatting. The useful ones summarize risk, list touched areas, and point out missing tests. They also flag changes that violate architectural boundaries, like a UI module reaching into persistence code. That is not “AI magic.” It is rules plus codebase context.

We still do not let bots approve merges. They can suggest, but humans own the decision. The bot is there to reduce the chance that a reviewer misses something obvious because the diff is long and the deadline is close.

How teams actually integrate AI into delivery

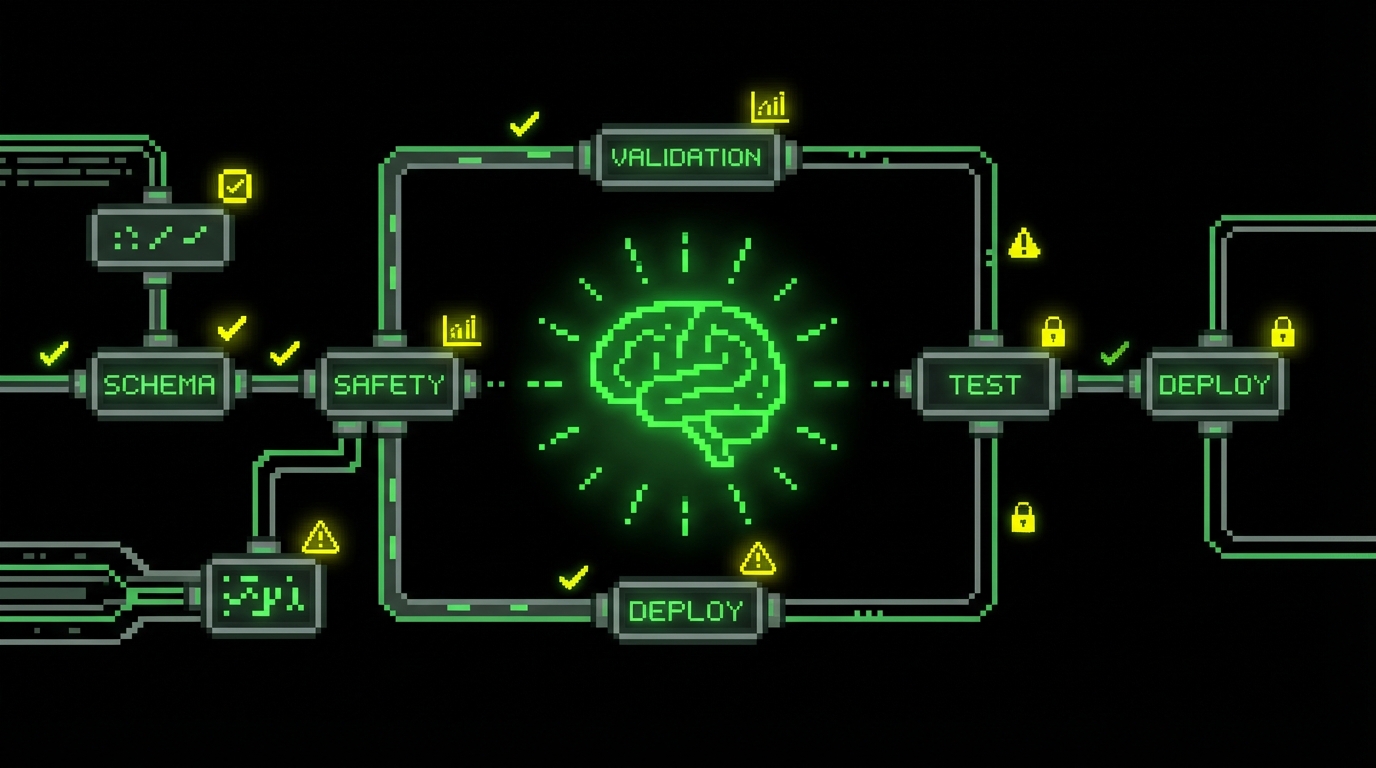

The integration problem is not “which model is best.” It is “how do we keep changes small, verifiable, and aligned with product intent.” In delivery, AI works when it sits inside an existing engineering system: tickets, acceptance criteria, code review, tests, and release gates.

On PoC and MVP work, the temptation is to let the assistant generate whole features fast. That can be fine if the goal is a demo in 4 to 12 weeks and you accept throwaway code. But even then, you need a thin spine of correctness: auth, data integrity, and basic observability. Otherwise the demo collapses under small changes.

A practical workflow we use on SaaS builds looks like this:

- Write acceptance criteria as testable statements. Keep them short and binary.

- Ask the assistant for a plan and file list before code. Reject plans that add new abstractions.

- Generate code in chunks that fit a single PR. Aim for under 300 changed lines when possible.

- Generate tests next. If tests are hard to write, the design is probably off.

- Run CI locally and in pipeline. Fix issues manually, then re prompt for small diffs only.

Prompting that engineers can review

Good prompts read like constraints, not like wishes. They name the exact module, the interfaces to keep stable, and the failure behavior. They also say what not to touch. That matters because assistants often “help” by refactoring unrelated code.

We also ask for explicit assumptions. If the assistant assumes “email is unique” or “timezone is UTC,” we want that in text so we can accept or reject it. Hidden assumptions are the main source of bugs in generated code.

Keeping AI output consistent with architecture

Consistency comes from templates and guardrails. A repo with a strong baseline (lint, formatting, type checks, test helpers, request validation) produces better AI output because the assistant can imitate it. A repo with mixed patterns invites mixed output, and reviewers end up debating style instead of correctness.

On Apptension projects like SmartSaaS style builds, we lean on a proven boilerplate to reduce variation. That is not about speed alone. It narrows the space of “valid” code so the assistant’s suggestions are easier to evaluate and less likely to introduce new patterns.

Guardrails: tests, types, and policies that make AI boring

If you want AI-assisted development to be safe, you need boring constraints. “Boring” means deterministic checks that fail loudly. The assistant should not be trusted to self validate. It should be forced to pass the same gates as human code.

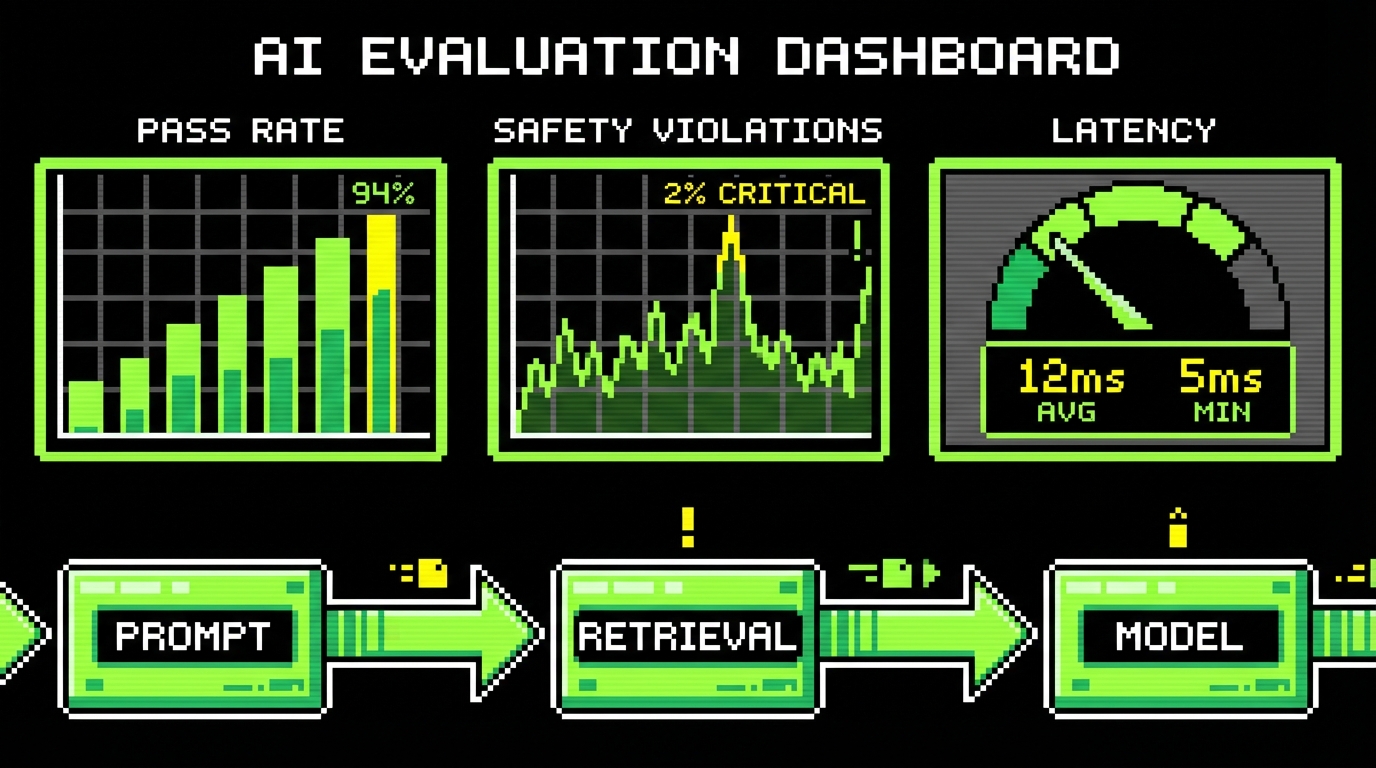

The three guardrails that pay off most are: strict typing, strong tests, and policy checks in CI. They catch different classes of mistakes. Types catch shape mismatches and null handling. Tests catch behavior errors. Policies catch dependency and security issues.

- TypeScript strict mode with no implicit any and strict null checks.

- Schema validation at boundaries (API requests, webhooks, background jobs).

- Contract tests for internal APIs and external integrations.

- Dependency policies to block risky packages or licenses.

Example: boundary validation that prevents “helpful” bugs

Assistants often skip validation because it looks like boilerplate. In production systems, boundaries are where bad data enters. If you validate at the edge, the rest of the code becomes simpler and the assistant’s internal changes are less risky.

Here is a small TypeScript example using a schema to validate input and keep types aligned. The point is not the library choice. The point is that the runtime check and the static type come from the same source.

import {

z

} from "zod";

const CreateProjectInput = z.object({

name: z.string().min(1).max(120),

ownerId: z.string().uuid(),

plan: z.enum(["free", "pro", "enterprise"]),

});

type CreateProjectInput = z.infer;

export async function createProject(raw: unknown) {

const input: CreateProjectInput = CreateProjectInput.parse(

raw); // From here, input is typed and validated. // AI-generated code inside this function is easier to review. return { id: crypto.randomUUID(), name: input.name, ownerId: input.ownerId, plan: input.plan, createdAt: new Date().toISOString(), };

}CI policies that stop unsafe diffs

In 2026, the fastest way to lose trust in AI output is to merge code that passes unit tests but breaks security expectations. That happens when tests do not cover auth edges and when CI does not enforce basic policies. You can reduce this risk with a few hard rules.

Examples that work well in practice:

- Fail CI if coverage drops on core modules, even if overall coverage stays flat.

- Fail CI if new endpoints lack request validation and auth middleware.

- Block merges that add direct SQL string concatenation outside vetted helpers.

- Require a human security review label for changes touching auth and billing.

Failure modes we keep seeing (and how to detect them early)

AI mistakes in 2026 are less about syntax and more about intent. The code compiles. The tests might even pass. The bug is that the code implements a different rule than the product needs, or it handles a failure path in a way that looks reasonable but is wrong for your domain.

We see a few repeats across data management products, internal platforms, and SaaS apps. They are predictable enough that you can add checks and review prompts to catch them early.

Hallucinated APIs and “almost right” library usage

The assistant will sometimes call methods that do not exist, or use an option name from an older version of a library. Type checks catch some of this, but not all. The tricky case is when the method exists but behaves differently than assumed.

Detection is boring: pin versions, run integration tests, and keep examples close to code. When we integrate third party services, we keep a small “golden path” test that runs against a sandbox or a recorded mock. That test fails when the assistant wires the SDK wrong.

Silent error handling and logging that hides the real issue

Assistants often wrap code in broad try/catch blocks and return generic errors. That makes demos look stable but makes production debugging painful. In data-heavy systems, silent failures can also corrupt downstream analytics because the pipeline keeps running with partial data.

We prefer explicit error types and structured logs with stable fields. If the assistant adds logging, we check that it includes identifiers we actually use: request id, user id, job id, and integration name. If it cannot include those, the log line is usually noise.

Tests that mirror implementation instead of behavior

Generated tests often assert internal calls and mock everything. They pass even when behavior is wrong. The smell is a test file full of mocks and no assertions about outputs, persisted state, or API responses.

We push the assistant toward behavior tests by giving it a template: arrange inputs, call the public function, assert on output and side effects, and avoid mocking the unit under test. When tests become hard under that constraint, it signals that the design needs clearer boundaries.

Patterns that work well in SaaS and data management builds

AI is most helpful when the system has clear seams. SaaS and data management products often do: API boundaries, background jobs, ETL steps, and UI components. If you define those seams, you can ask the assistant to work inside them without touching the core.

On projects similar to Tessellate or Platform style work, we often deal with complex data flows and permission models. AI can draft the first pass of mapping code and tests, but we keep human ownership of the domain rules. We also keep “source of truth” documents as code: schemas, migrations, and permission matrices in version control.

Example: generating a safe background job with idempotency

Background jobs are a common place where assistants produce code that works once and fails under retries. In 2026, most systems still need retries because networks fail and third party APIs throttle. The fix is to make jobs idempotent and to record progress.

This simplified example shows the shape. It uses an idempotency key and a stored status. The assistant can help fill in the boilerplate, but the policy matters more than the syntax.

type JobStatus = "started" | "completed" | "failed";

type JobRecord = {

id: string;key: string; // idempotency key status: JobStatus; updatedAt: string;

};

const jobStore = new Map();

export async function runSyncJob(key: string, fn: () => Promise) {

const existing = jobStore.get(key);

if (existing?.status === "completed") return;

jobStore.set(key, {

id: existing?.id ?? crypto.randomUUID(),

key,

status: "started",

updatedAt: new Date().toISOString(),

});

try {

await fn();

jobStore.set(key, {

..(jobStore.get(key) as JobRecord),

status: "completed",

updatedAt: new Date().toISOString(),

});

} catch (err) {

jobStore.set(key, {

..(jobStore.get(key) as JobRecord),

status: "failed",

updatedAt: new Date().toISOString(),

});

throw err;

}

}UI work: fast scaffolds, slow correctness

On the front end, assistants are good at scaffolding components, forms, and state wiring. They are weaker at accessibility details, subtle layout bugs, and performance pitfalls with large lists or heavy charts. The UI still needs human review with real data and real devices.

We often ask the assistant to generate the first draft of a form plus validation schema, then we manually verify keyboard navigation, error messages, and loading states. If the product has a design system, we force the assistant to use only existing components. Otherwise it invents new patterns and the UI drifts.

Conclusion: treat AI as a tool, not a teammate

AI-assisted development in 2026 is useful when you can verify outputs quickly. That means strict types, validation at boundaries, meaningful tests, and CI policies that block risky changes. It also means small PRs and clear acceptance criteria. Without those, the assistant mostly creates work you pay for later.

The balanced view is simple. AI speeds up the parts of engineering that are repetitive and easy to check. It slows down the parts that depend on product intent, edge cases, and failure behavior. If you want steady delivery, keep humans responsible for the rules and let the assistant handle the scaffolding.

If you cannot describe a change as a small diff with a clear test, do not ask an assistant to implement it end to end.

For teams building PoCs, MVPs, or full SaaS products, the practical goal is not maximum code generation. It is predictable throughput. When AI fits inside your engineering system, it can help you ship more reliably. When it replaces that system, it tends to amplify the mess.